I never imagined for one minute that my previous works on Third Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment during World War II would lead to something quite like Sign Here for Sacrifice. However, the synergy between the battalion’s wartime commander Bob Wolverton and the Vietnam-era John Geraci is uncanny, as is the strength of character regarding both the officers and men. The men of ’67 accepted that they were being groomed to actively participate in a faraway war. To be a paratrooper is to be part of a special brotherhood. These young troopers stood every inch as tall as their forebears in World War II. Twenty-two years later, it was their turn to carry the “Currahee” flag into battle and they did not intend to disappoint their leadership or country. Whether or not the Vietnam War was worth fighting is a discussion that we do not enter into in this book. Although politics is occasionally touched upon, it is first and foremost a story of service and duty.

For those of you who may be unaware of America’s journey to war, this is just a brief overview of what ultimately led these young men to board a slow boat to South East Asia for this first tour n 1967.

The clock began ticking during the last weeks of World War II, when the battle-hardened troopers from Third Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division were moving into Adolf Hitler’s mountain home. Virtually at the same time, on the other side of the world in Southern China, a meeting was taking place between Nguyen Ai Quoc and the American Office of sign here for sacrifice Strategic Services (OSS). The 54-year-old exile had been and still was a major player in the communist revolutionary program dating back to the 1920s. Now reborn as Ho Chi Minh, which meant “Bringer of Light,” Ai Quoc appeared disheveled and fragile as he sought US support for the independence of his country.

The three regions that made up Ho’s country – Cochin China, Annam, and Tonkin – had been under French colonial control for the last 100 years, and at that time were still occupied by the Japanese. Although transparent about his political ambition, the future President of North Vietnam was determined to rid his country of both powers. As a scholar and teacher, Ho was well educated, and between the wars traveled to America, Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and China – where he married. In the early 1930s, at the request of the French, who had previously sentenced Ho to death, he was arrested in Hong Kong and put on trial by the British, who soon came under pressure from France for extradition. But on appeal, the matter was settled “out of court” and Ho escaped incognito to Moscow, where he continued to study and teach.

Six years later, Ho relocated to China and served as advisor to the Chinese communist armed forces. In 1941, he returned to Annam to lead the newly formed Viet Minh Independence Movement. The term “Viet Minh” was short for “Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh Hoi.” Created as a guerrilla force, the Viet Minh fought to overthrow their Japanese and French Vichy occupiers. Ho engineered many successful insurgent actions, all under the watchful and clandestine support of the United States.

At the end of World War II, the Viet Minh were powerless to stop either the Chinese, who accepted Japan’s surrender in the North; or the British, who took surrender in the South. When General Dem Gaulle, leader of the Free French forces, demanded that China and the UK hand back control of “French” Indochina, his allies could do nothing but comply.

In September 1945, Ho Chi Minh declared independence from France and announced the creation of his Democratic Republic. The term “Viet” and “Nam” came from a conjunction of two old ethnic words, meaning “beyond” or “outsider” and “southern territory.” In 1949, in an attempt to undermine Ho, France encouraged exiled Emperor Bao Dai to return, and he became a figurehead for their revitalized colonial plan.

The new regime was quickly recognized by the US, Britain, and other Western countries primarily to thwart Ho’s growing communist expansion. But then Ho cleverly persuaded Bao Dai to abdicate and take on the honorary title of “Supreme Advisor.” Feeling out of his depth, the self-indulgent playboy fled, and over the next three years divided his time between Hong Kong and the French Riviera. Bao Dai’s sudden departure encouraged the Soviet Union and China to recognize and support Ho’s fledgling Democratic Republic. This action set Vietnam on course for the First Indochina War that culminated in the unexpected northern defeat of French armed forces at Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

Out of 11,000 French paratroopers taken prisoner at Dien Bien Phu, 60 percent never came back from the camps. However, Western powers paid no heed to the incredible human effort shown by Ho’s ill-equipped revolutionary force. Later, this turned out to be an inexcusable oversight for America, who after the Korean War (1950–53) dared to believe that it was possible to broker a successful balance between two regions. Today, few will understand that from the 1940s through to the Cuban Missile Crisis, America’s greatest concern was the spread of communism.

When the French withdrew after Dien Bien Phu, Bao Dai returned and attempted to form a working government for Vietnam. On July 21, 1954, the Geneva Accords ended the First Indochina War along with French rule, effectively dividing the nascent country into two zones – north and south. However, Washington thwarted the emperor’s plans by urging him to appoint the exiled politician Ngo Dinh Diem as prime minister for the South. As a devout Catholic, Diem had gathered much popularity within the Vatican, along with many US political and religious leaders. As the Geneva Settlement was never officially ratified, conflict quickly resumed, albeit without French intervention.

Diem was now political and military leader with Bao Dai as his figurehead and ceremonial chief. The following year, by way of a rigged referendum, Diem removed Bao Dai and his Nguyen Dynasty from power, declared the South a republic and himself president. Bao Dai wanted no part in Diem’s Southern plan and fled back to France, never to return. The “last emperor” spent the remainder of his life in Paris and even found time to write a book called Le Dragon d’Annam. Ho’s OSS meeting in 1945 could never have foreseen these shattering events that two decades later would spawn a war that cost another two million Vietnamese and over 58,000 American lives.

For the men in this book, the story really begins in December 1967, when the professional volunteers of the Third Battalion of the 506th Airborne (3/506) were sent west from their Southern coastal base at Song Mao into the Central Highlands and province of Lam Dong. The new mission coincided with a build-up from the Chinese-supported North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and proved a gritty introduction to the reality of a dirty, sweaty, insect-ridden war. Moreover, the Viet Cong, who would fight alongside the NVA, were not just a military force; they were a society equipped with total faith and the resolve to win. They would prove to be a determined, resourceful, and experienced enemy to the men of 3/506.

After New Year 1968, the battalion moved south by road back to the coast and Phan Thiet. The NVA had spent six months preparing and were now ready to unleash their forces across Southern Vietnam. The Tet Offensive began on January 31 with a coordinated series of deadly attacks. Now a specialized and self-sufficient task force, 3/506 along with South Vietnamese government and local forces were at the very heart of this month-long battle. Fighting in and around Phan Thiet was brutal, but the Currahee tenacity eventually prevailed. There was no other period like it and these young paratroopers made their mark in the dusty rice paddies and corpse-strewn streets.

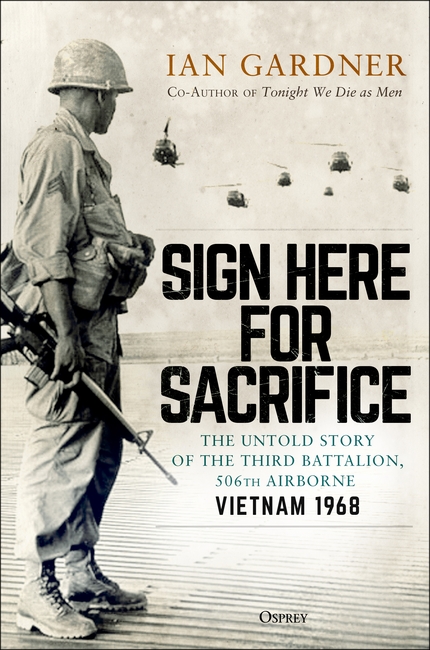

Members of C Co at Song Mao in early December 1967. (“Bucky” Cox Archive –

Author’s Collection)

If you enjoyed this extract you can order the book in hardback and digital formats here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment