On the blog today authors Nigel Thomas and Dusan Babac introduce us to the Yugoslav army.

On 25 November 1918, barely two weeks after the end of the Great War, the Kingdom of Serbia, a central Balkan state which had triumphed as an Allied Power, annexed its principal southern Slav neighbours Croatia and Slovenia to form ‘The Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes’ (usually abbreviated SHS). The new state was effectively a Greater Serbia, governing substantial minorities of German immigrants, Montenegrins, Bosnian Moslems, Vardar Macedonians, Albanians, Hungarians, Italians, all of which, with the possible exception of Montenegrins (who considered themselves Serbs), resented forced inclusion in SHS.

The Serbs felt entitled, after heavy losses sustained in the Great War, to rule the western Balkans. Serbo-Croatian politics became increasingly violent and, after a gunfight in the SHS parliament, the Croats boycotted further parliamentary business. On 6 January 1929, King Alexandar I took advantage of the stalemate to introduce a personal dictatorship and rename SHS as ‘Yugoslavia’ Land of the South Slav, thereby further alienating the other nationalities. On 9 October 1934, Alexandar was assassinated in Marseilles by Macedonian and Croatian extreme nationalists, leaving Prince Pavle as Regent. On 24 August 1939, Pavle attempted to appease the Croats by forming the Province (Banovina) of Croatia as an autonomous state, but already the Croatian ‘Ustasha’ extreme nationalists were plotting to replace Yugoslavia with a Nazi-style Croatian state.

Between the Wars

The Yugoslav Army (Jugoslovenska Vojska), often incorrectly called the ‘Royal Yugoslav Army’, counted about 148,000 men in peacetime, with 28 infantry divisions, three mounted cavalry divisions and a divisional-sized Royal Guard. Army organization followed the Balkan and Central European model, with dismounted, mountain and border infantry, obsolete mounted cavalry and light tanks, a strong artillery branch, horse-drawn transport and a short engineer, medical and administrative ‘tail’. By 1939, Yugoslavia had begun to modernize, forming some mechanized and motorized infantry units and ‘Chetnik’ (guerilla) assault battalions for strikes behind enemy lines. The Serbian monarchy had survived the Great War with its prestige enhanced and so Yugoslavia proudly preserved royal traditions with the prestigious and sizeable Royal Guard, dressed in ornate and colourful uniform, with regimental ciphers commemorating European and Serbian royalty.

On 7 June 1921, the SHS joined Czechoslovakia and Romania in the ‘Little Entente’, a mutual defence pact against Hungary and Austria, who were still bitter at the loss of territory after the Great War. France, a European great power, guaranteed the alliance, but by the mid 1930s France had lost the will to support the Entente and remained passive as Nazi Germany occupied the Rhineland on 7 March 1936, annexed the Sudetenland on 30 September 1938 and occupied western Czechoslovakia on 15 March 1939. Nevertheless Yugoslavia, by tradition pro-Allied, tried to avoid participation in World War II by signing the Axis ‘Tripartite Pact’ on 25 March 1941. This led to an Army coup on the 27 March and cancellation of Yugoslavia’s membership of the Pact. Enraged by Yugoslavia’s defiance, Hitler ordered the Axis invasion.

Before the start of World War II, the Yugoslav General Staff had already planned an organized retreat to the impenetrable mountains of Bosnia, with the intention of employing guerrilla tactics to defeat any enemy. However the Yugoslav government unrealistically insisted that the Army defend every yard of the border, a task for which they were neither trained nor large enough. Furthermore divisions were mobilized within their own military districts meaning that the members of the Croatian 27 Savska and 49 Slavonska divisions, mustered to 4 Army and the Slovene 32 Triglavska Division in 7 Army defended the north-eastern border of a state to which they owed no allegiance.

The ’April War’ lasted from 6 to 18 April 1941. On 9 April, Savska, Slavonska and Triglavska deserted to the Germans, fatally weakening the Northern Front. In addition, Croatian and Slovene deserters assisted ethnic Germans and disarmed Yugoslav troops, Meanwhile Serbian divisions of 3 Army, who had offered determined resistance in Serbia and Vardar Macedonia, were unable to prevent the Army surrender in Belgrade.

Germany annexed Slovene Carinthia, Upper Carniola and Southern Styria. Italy annexed Western Slovenia as Lubiana Province, added more Dalmatian districts to Zara Province, occupied Montenegro and awarded south-west Montenegro, Kosovo, Debar and Struga districts to Italian-occupied Albania. Vardar Macedonia and parts of eastern Serbia was annexed by Bulgaria. Croatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina and Syrmia formed the ‘Independent State of Croatia’ (NDH). The former Hungarian border districts of Prekmurje, Medjimurje, Baranja and Bačka were restored to Hungary. Serbia, reduced to its 1912 borders, was ruled by the collaborationist Serb General Milan Nedić, reporting to the German Military Government. Finally Serbian Banat was administered by its German minority.

These 1941 Yugoslav borders, although imposed by enemy forces, displayed an ethnic logic which was repeated in the post-war period.

Yugoslav Army in the Middle East

With Yugoslavia under enemy occupation, the Yugoslav Army followed the example of Czechoslovakia, Poland, Norway, Denmark, France, Belgium, Netherlands and Greece by establishing military forces, popularly referred to as ‘Free Brigades’ to demonstrate, especially to its allies, that Yugoslavia remained an active belligerent.

Virtually none of the Yugoslav Army had escaped capture by the Axis forces in the April War, and so the Royal Yugoslav Guards Battalion, formed in June 1941 in Cairo, mainly comprised of 530 Croatian and Slovene soldiers, serving in the Italian Army and taken prisoner by the British 8th Army in North Africa. By February 1942 the Slovene officers had turned the battalion into a small, but credible fighting force which could have expanded to brigade strength, thereby inviting comparison with the other Free Brigades, but the battalion was dogged by poor discipline. In early 1942, inter-officer rivalry in the ‘Cairo Affair’ exasperated the British who refused to establish any more infantry battalions. In March 1943, the British moved support from the Yugoslav-Serb general, Mihailović, to Tito leading to nationalist-communist rivalry arguments and fist-fights in the Royal Yugoslav Guards, now only company-strength. It was disbanded in March 1944. The proud Yugoslav Army was gone.

Chetniks

There is a long tradition of guerrilla warfare in the Balkans, where armed civilians defended their villages from foreign invaders from about 1450. Serbian guerrillas, (singular: Chetnik) fought against the Ottoman Army of Occupation but also rival Greek, Bulgarian and Macedonian bands from 19041912. Chetnik units then played a leading role in the two Balkan Wars (191213) and the Great War (191418) but suffered high casualties. After the Great War, several Chetnik and other associations competed for the Yugoslav, especially Serbian, nationalist vote, the most prominent player being the Chetnik Association formed in 1921, and commanded from 1932 by the charismatic leader (Vojvoda) Konstantin ‘Kosta’ Pećanac. The Yugoslav government used Chetniks to suppress rebel Bosnian and pro-Bulgarian Vardar-Serbian guerrilla forces.

Following the defeat of the Yugoslav Army in the April War, General Staff Colonel Dragoljub ‘Draža’ Mihailović formed a guerrilla army on Ravna Gora Mountain, near Valjevo, Serbia, called ‘Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army’, ‘Military-Chetnik Detachments’ or the ‘Ravna Gora Movement’. Soon the Chetniks were recognized by the Allies as the official anti-Axis opposition and redesignated on 11 January 1942 as ‘The Yugoslav Army in the Homeland’, in opposition to the Communist Partisans under Josip Broz Tito. From 1941 to 1944 the US Army and British Army sent liaison officers, supplies and munitions.

The Ravna Gora Movement claimed to be a political movement but Mihailović’s politics consisted of Serbian supremacy. Chetnik propaganda maps showed a future Yugoslavia as three quarters Serbia with starkly reduced Croatian and Slovene enclaves and other nationalities, including Bosnian Moslems, ignored.

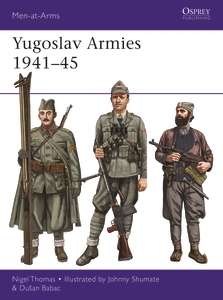

As the representative of the pre-1941 Yugoslav Army, the Chetniks wore a mixture of Army and enemy uniforms and civilian-contrasted clothes. Military rank-titles and promotions, cap and unofficial unit badges were worn but rank insignia was omitted. Many Chetniks vowed not to shave their beards until the Chetnik victory; thus Chetnik troops offered a piratical appearance which contrasted markedly with the clean-shaven Partisans. Kosta Pećanac’s Chetniks fought under German command from summer 1941 but their unreliability led to their disbandment in September 1942.

After initial military enthusiasm, Mihailović became more reluctant to attack the German, Italian and Bulgarian occupation forces, lest the Chetniks provoke savage reprisals on the Yugoslav civilian population. Following Chetnik tradition, Mihailović’s commanders defended their territory with minimal force, and some even formed temporary battlefield alliances against the Partisans, to join in 1943 a widely expected Allied invasion of the Yugoslav coast to then defeat the Partisans. This misjudged strategy greatly damaged the Chetnik cause. In fact by 1943 the Chetniks and Partisans were fighting a civil war and the Chetniks were being forced back to Serbia. In March 1944, the British moved support from Mihailović to Tito and the Chetnik cause was henceforth living on borrowed time. Mihailović marched northwards, abandoning Serbia in October 1944, and reaching Allied lines in Slovenia in April 1945. Some Chetniks surrendered in North Eastern Italy in May 1945, but Mihailović turned back towards Serbia, only to be defeated by the Partisans in Bosnia.

Draža Mihailović was captured by Partisans in Bosnia in March 1946 and was shot by firing squad in Belgrade in July 1948 after a show-trial. Communist Yugoslavia regarded Mihailović as a pro-Nazi traitor, but more recent Serbian historiography is more sympathetic to an old-fashioned Serbian officer who supported the Allies and the Yugoslav monarchy to his dying day.

Yugoslav People’s Liberation Army

By June 1940, Germany’s mechanized armies had forced the surrender of Poland, Denmark, Norway, Belgium and Netherlands. These conquered states all organized resistance armies from troops who had avoided capture, supported by civilian patriots, but none of them constituted a serious threat to German hegemony. The Yugoslav surrender in April 1941 was different, since large numbers of Yugoslav troops remained at large in mountainous country which favoured guerrilla warfare. In fact two resistance armies developed in Yugoslavia: the Chetniks (already discussed) and the Partisans.

Josip Broz (nicknamed ‘Tito’), a Croat, was a dedicated communist activist loyal to Stalin’s Soviet Union. He joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) on its formation on 23 April 1919, served in the 1930s as a Comintern agent, promoting world communism, became KPJ Secretary General in August 1937, and Chairman of the Military Committee on 10 April 1941, effectively Partisan commander. Unlike Mihailović, Tito was not a career soldier, although he had been the youngest sergeant in the Austro-Hungarian Army during the Great War. He was however a charismatic political leader. Mihailović’s narrow traditional political views limited the Chetniks’ appeal to Serbian nationalists. Tito, however, reached out beyond the KPJ base to all Yugoslav nationalities and political philosophies, asking all patriotic Yugoslavs to join him in resisting the Axis invader, postponing a final Yugoslav settlement until after the war. This apparently inclusive political appeal encouraged Serbs and other nationalities to join the Partisans, and Great Britain and USA to supply large quantities of munitions and supplies.

The handsome, charismatic and urbane Croat, who downplayed his communist principles, offered the Western Allies and many Yugoslavs a refreshing contrast to the apparently passive Chetniks and Stalin’s die-hard Soviet communists, but Tito’s demeanour concealed a ruthless Marxism which had saved him from Stalin’s purges in 1930’s Soviet Union. The Partisans won a reputation as reliable fighters, and Tito, unlike Mihailović, had no compunction about risking German massacres by attacking Axis troops. Front-line Partisans were subject to control by the feared ‘Department for People’s Protection’ (OZNA) internal security apparatus.

If Mihailović sought inspiration from traditional Chetnik guerrilla tactics, Tito planned a modern mechanized Army. Tito’s commanders derived their military and political skills, uniforms and insignia, from the Spanish Republican Army during the Spanish Civil War 193639. By January 1945, the People’s Liberation Army, a vulnerable guerrilla army with light weapons had become the ‘Yugoslav Army’ organized into four field armies with tanks, artillery and automatic weapons, air and naval arms, wearing British and home-manufactured uniforms, continuing with Soviet Red Army and Bulgarian Army support, to drive admittedly exhausted German forces out of Yugoslavia. Thus Tito could state, with almost complete justification, that Yugoslavia was the only country to have liberated itself from enemy occupation.

It would be a mistake, however, to accept Tito’s self-promotion as a loyal ally of the West and the Soviet Union. In May 1945, he attempted to annex the Trieste region by force, and from 194548, resisted Stalin’s attempts to form a Yugoslav-Bulgarian-Albanian federation, leading the Soviet dictator to banish Yugoslavia from the Cominform in June 1948. Now Tito moved closer to the West, accepting economic and military aid from the United States.

Tito died on 8 May 1980. Yugoslavia was now a federation of autonomous states, previously kept intact by Tito’s charisma, political skill and ruthlessness. The federation limped along until August 1990 when the state collapsed into the seven independent states - Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, Northern Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Slovenia, that we know today.

Yugoslav Armies 1941–45 is out now and can be purchased in all formats from our website!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment