In today's blog post, authors Klaas Castelein and Michel Wenting introduce us to the Dutch Resistance during World War II and share some photos from their research trip for the book!

Growing up in the Arnhem area of the Netherlands, both of us, Michel Wenting (born in 1965) and Klaas Castelein (born in 1983), were forever stumbling upon remnants from World War II. The defunct Westervoort Fortress, strategically located along the Arnhem side of the IJssel River, was the scene of brief but intense fighting during the May 1940 campaign, and Arnhem became infamous when, in September 1944, British and Polish airborne troops failed to secure the Rhine Bridge as part of Operation Market Garden. However, our interest in World War II is not wholly attributable to the tangible war remains from our childhoods, but also to our family connections to the wartime resistance movement: Michel’s great-uncle, Antoon Helmes, was involved in sabotage and providing shelter to shot-down Allied pilots, while Klaas’ great-grandparents, Hielke and Gelske Brouwer, aided persecuted Jews in hiding (for which they posthumously received the ‘Yad Vashem’ award). Listening to these stories first hand inspired us to research the part the Dutch Resistance had played during World War II and, using original language sources in Dutch coupled with extensive research and interviews with Dutch World War II experts, we were able to dig deeply into its workings and provide a synopsis of a topic we felt was important for Osprey to publish.

ELI 245: The Dutch Resistance 1940–45 is not just about the Dutch Resistance but also about the emergence of fascist organizations in the pre-war era and the various forms of Nazi collaboration that followed. The National Front (NF), which existed from April 1940 until December 1941, boasted a short-lived paramilitary wing known as the Grauwe Vendels (Grey Banners, GV). During our research, we found only three black-and-white photographs displaying GV paramilitaries, and eager to compose the first visual reconstruction of a GV member and determined to establish the correct colours for the uniform’s sidecap, shirt and breeches, we consulted the online memoirs of a former member who described everything but the colours for the sidecap’s piping and frontal tassel. We then paid a research visit to the Brabant Historical Information Center (BHIC) in the southern city of Den Bosch, where the entire NF/GV archive is stored and, among thousands of records, located a highly detailed description of the uniform, revealing that the sidecap’s piping and tassel were in fact light-grey. A fully substantiated description of the figure was then delivered to the editor and to the illustrator, Mark Stacey, commissioned to create the title’s full-colour artwork.

In November 2020, the authors made an epic research trip to the BHIC in Den Bosch, home to the entire NF/GV archive. When they finally established the colour of the GV sidecap’s piping and tassel, it felt like finding the Holy Grail. (Left photo, Klaas Castelein, right photo, Michel Wenting, digitally edited by Sjoerd van der Zande.)

ELI245 contains eight colour-artwork plates, displaying twenty-one figures (divided into eleven fascists and collaborators and ten resistance members) plus eight types of brassards worn by the Dutch Resistance. In addition to the NF/GV party militant, it contains three other uniforms that have never been visually reconstructed as far as could be ascertained: a Dutch watchman serving in the German military, a Kontroll Kommando (KK) camp guard and a Dutch national serving in the Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labour Service, RAD) on the Eastern Front.

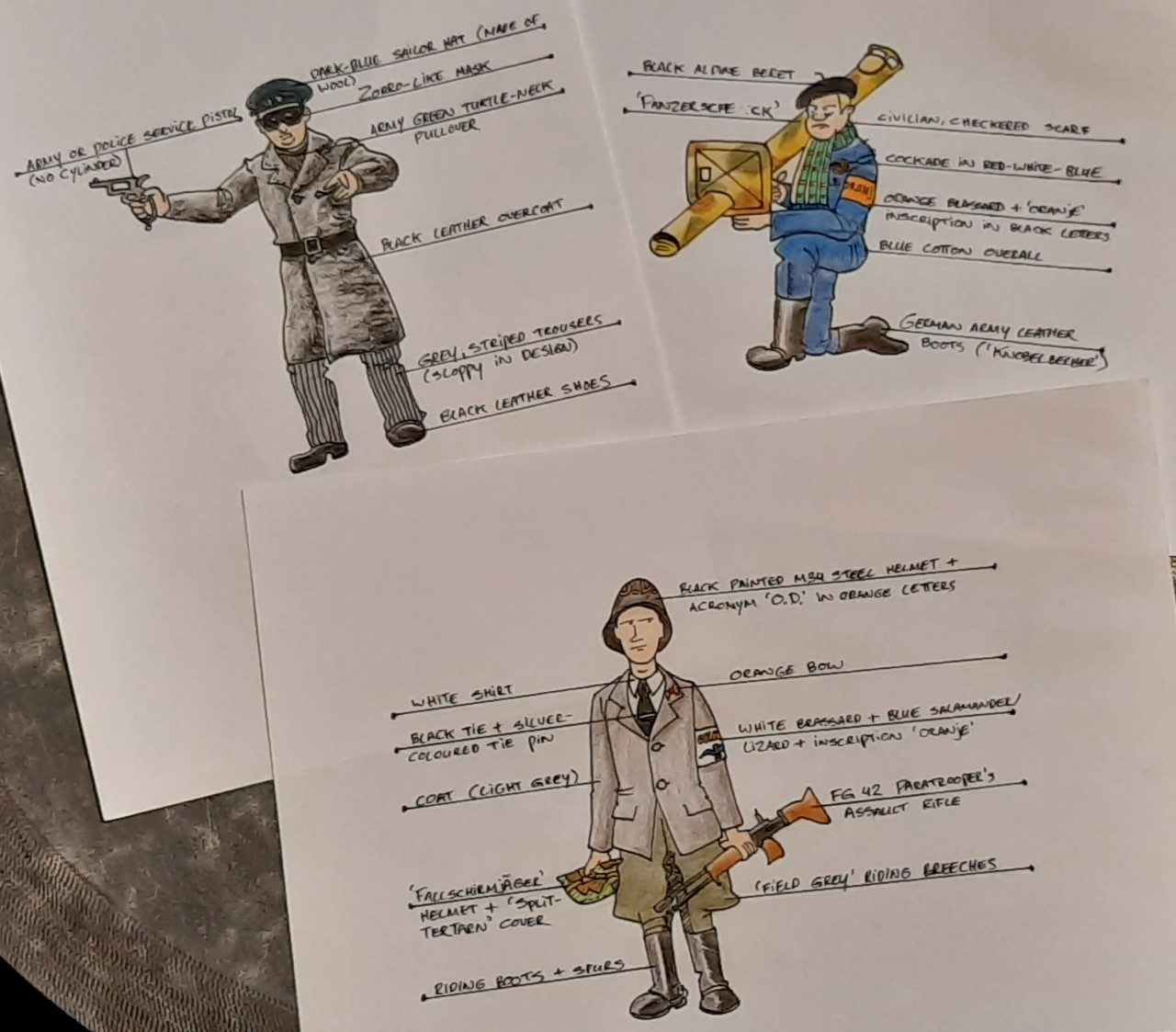

For most figures Klaas drew a cartoon-like drawing of himself to convey the picture as accurately as possible to both the editor and artist. The drawings above show three different types of Dutch resistance fighters. (Drawings and photograph by Klaas Castelein.)

The length of this blog does not allow us to go into too much detail as to the findings of our extensive research on the topic however we would like to highlight some points that may be of interest to readers.

Firstly, the Dutch Resistance was by no means a monolithic entity; resistance warfare was manifested in different layers of activity, sometimes intermixed and sometimes independent. The use of the term ‘Dutch Resistance’ within the book refers to all these different forms and sets out to describe them in their relative contexts.

Additionally, the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands was a great deal broader than is reflected by the much-reported German counter-espionage success against Dutch agents parachuted in by the Special Operations Executive (SOE), popularly known as the Englandspiel (England Game). This event is discussed in the book but only to explain the disastrous impact it had on the growth of the Dutch Resistance. When the British finally realized that agents and large quantities of supplies had fallen into German hands, they suspended airdrops until September 1944 and, as a result, the Dutch Resistance suffered from a dire shortage of weapons during the mid-war years.

Despite these setbacks the Dutch Resistance succeeded in gaining momentum from spring 1943 onwards. By then, three major armed resistance organizations had come to the fore, the Ordedienst (Order Service, OD), the Landelijke Knokploegen (National Assault Teams, LKP) and the Raad van Verzet (Resistance Council, RVV). Having ex-army personnel among its ranks, the OD was perceived by many as the underground continuation of the Dutch Army (defeated in May 1940), but we found that the OD also included a considerable number of civilian members, calling into question this image of a solely elitist and exclusive resistance organization run by ex-Army officers.

The LKP was always looked upon as a predominantly Protestant-Christian resistance organization but, again as we found, it gradually expanded its resistance activities across the whole of the predominantly Roman-Catholic southern part of the Netherlands (North Brabant and Limburg provinces), and created a religiously diverse membership and support-base to become a varied and inclusive organization both politically and religiously. Another popular misconception, that the RVV was a predominantly leftist or even communist resistance force is debunked. The RVV in the western province of North Holland contained a considerable number of communists and left-wing operatives but RVV members in other parts of the Netherlands had varied political and/or religious inclinations, making the RVV a pluralist force.

In September 1944, the resistance warfare in the Netherlands entered a new phase. The OD, LKP and RVV were merged into an umbrella organization known as the Nederlandse Binnenlandse Strijdkrachten (Netherlands Interior Forces, NBS). This merger was inspired by the Forces française de l’intérieur (French Interior Forces, FFI), which had actively contributed to the liberation of France. When the Allied forces reached the southern part of the Netherlands, local NBS groups surfaced and embarked on open warfare against the Germans in support.

Nazi authorities took various measures to counter the growing Resistance movement in the Netherlands, one of which was to raise a pro-German paramilitary force known as the Landwacht (Home Guard). Initially, the Landwacht was meant to protect members of the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (National Socialist Movement, NSB), the prime vehicle of collaboration in the Netherlands, from assassination attempts conducted by the armed Resistance, however, the Landwacht was also actively involved in hunting down Resistance members and persecuting people in hiding. During the final stage of the war, Landwacht paramilitaries served as combat troops alongside German forces in a fruitless bid to stem the Allied advance

After the failure of Operation Market Garden in September 1944, the frontline in the Netherlands more or less stabilized, cutting the country into an occupied northern part and a liberated southern part. This allowed NBS forces in the liberated south to be trained, equipped and uniformed by both the British and Americans, giving them the appearance of a regular force (the NBS in the occupied north retained their irregular and underground character until the very end of the war). These British and US-backed NBS forces became known as Stoottroepen (Shock Forces, ST). Common perception is that the NBS did not have enough men or weapons to help the Allied armies on the battlefield during the late phase of the war, but research uncovered that from the 14th until the 17th of April, 1945, NBS forces in Friesland virtually liberated the entire province ahead of the Canadian advance, prompting the commander of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division to write that ‘Friesland liberated herself’.

Within ELI 245, we have attempted to correct and balance previous historical accounts to achieve a more accurate retelling of the subject. We hope you enjoy reading ELI 245: The Dutch Resistance 1940–45 and discovering more in-depth information about the Dutch Resistance during World War II.

Co-authors Klaas Castelein (left) and Michel Wenting (right) proudly showing their advanced copies of ELI 245: The Dutch Resistance 1940–45 at the Stoottroepen (Shockforces, ST) Monument in Beneden-Leeuwen in late February 2022. (Authors’ photo)

If you enjoyed today's blog post you can purchase a copy of the book on our website in paperback or digital formats.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment