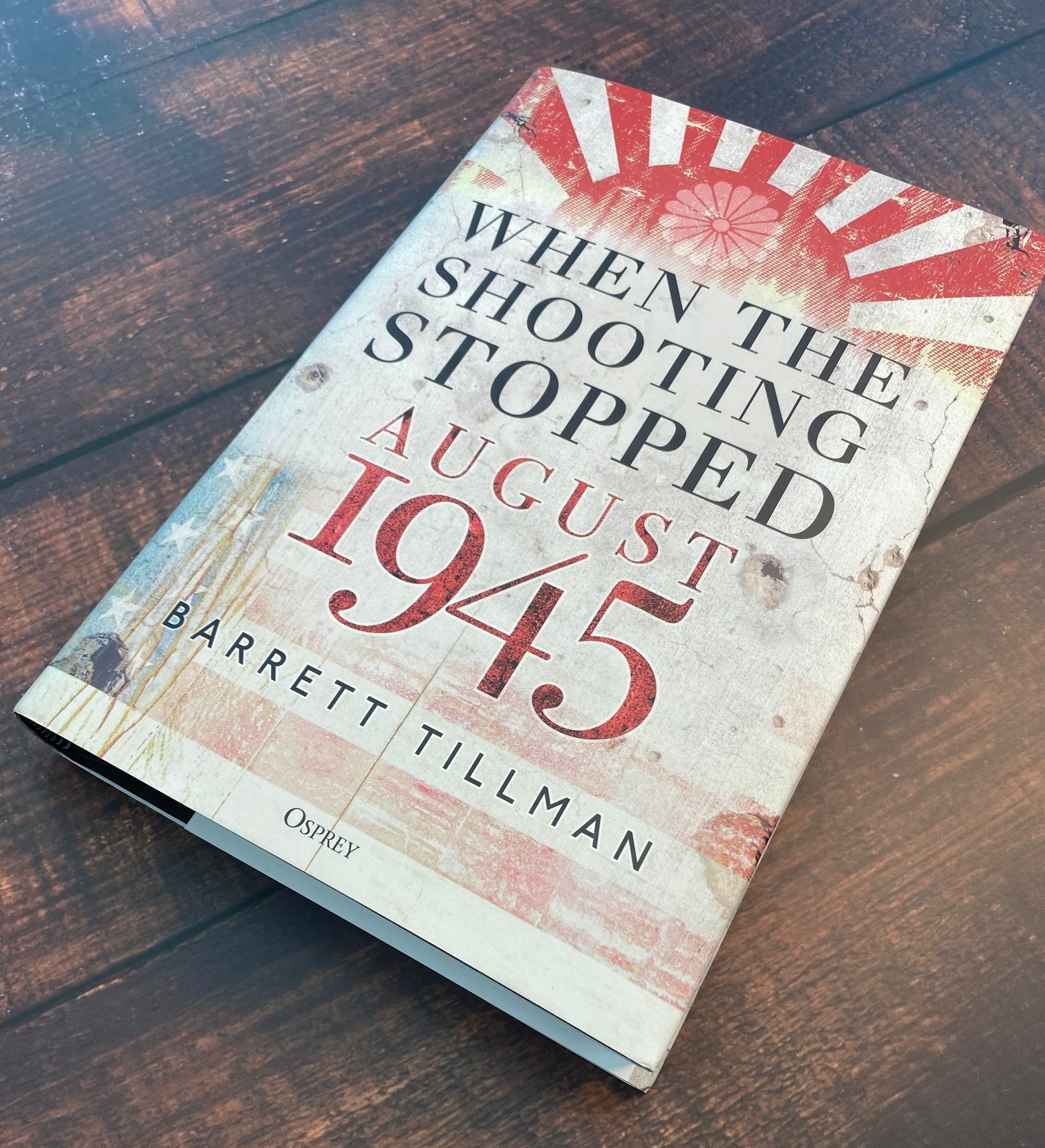

Today is VJ Day and to mark the occasion we're sharing an extract from Barrett Tillman's When the Shooting Stopped: August 1945

Seen from space, Earth’s dominant feature is the Pacific Ocean. Its 62.5 million square miles cover more than one-third of the planet’s total surface. Nothing else comes close. For comparison, San Diego to Tokyo is 5,500 statute miles; even from Honolulu, Tokyo is over 3,800, while New York to London is less than 3,500.

In forty-four months between December 1941 and August 1945, the Pacific Theater of Operations absorbed the attention of the American nation and military longer than any other. Despite the Allied grand strategy of “Germany first,” after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. was irrevocably committed to confronting Tokyo as a matter of urgent priority. American ground troops did not engage the Western Axis in North Africa until November 1942 and did not fight on the European mainland until almost a year later.

Allied forces were engaged elsewhere, most notably in the China-Burma-India Theater. But the development of what British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called “triphibious operations” was necessarily perfected in the Pacific—a melding of land, sea, and air forces that took giant steps across 153 degrees of longitude from Oahu to Tokyo. It was a long, sanguinary slog, averaging an advance of three miles per day. The U.S. human toll paid on that road reached some 108,000 battle deaths, more than one-third the U.S. wartime toll. The last of 185,900 American combat losses in the Atlantic-European-Mediterranean theaters ended with VE Day in May.

In the summer of 1945 the nation was distressingly accustomed to mounting attrition. The first week in August added 7,489 dead, missing or wounded, bringing the wartime total to 1,068,216 casualties. That meant 1,070 casualties a day—the price of doing wartime business.

Therefore, by the time of Victory Over Japan (VJ) Day, the wartime generation of Americans received a concentrated course in geography. Allegedly few had ever heard of Pearl Harbor in 1941, but four years later the large majority knew the significance of Guadalcanal, Saipan, Leyte Gulf, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.

But there was hope—growing, even soaring hope. The stunning announcements of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9 seemed sure to force Tokyo over the tipping point after the Allies’ surrender demand from Potsdam, Germany, in July, two weeks before Hiroshima. Without indicating nuclear weapons, the Allied declaration stated, “We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

To most Americans, the threat of “prompt and utter destruction” was justified, however delivered. The immense devastation of conventional and nuclear bombing seemed only fitting, given revelations of Japanese atrocities from the Rape of Nanking in 1937 to the Bataan Death March in 1942, to attacks on Allied hospital ships in 1944 and 1945.

Much as Americans wanted to believe that Japan would capitulate, many remained wary. They recalled the apparent treachery of December 7, 1941 when two envoys were filmed visiting the U.S. State Department while bombs and torpedoes slaughtered U.S. ships, sailors, and soldiers in Hawaii.

What few understand today is the vast gap—more of a chasm—in the cultural ethos of East and West. Later, Japanese war criminals could not be specifically indicted because Western military law had no strictures against cannibalism.

In the war zones, at home and abroad, people treaded a tenuous trail between continuing war and impending peace.

If you're interested in learning more about the end of WWII, you can buy a copy of the book here which is cureently included in our summe sale until 31st August! You can get 30% off the hardback and 40% off digital products.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment