On the blog today, William Suttie, author of Chobham Armour explains where his interest in tanks began.

FV432 being used for training on Salisbury Plain. (Crown Copyright MOD)

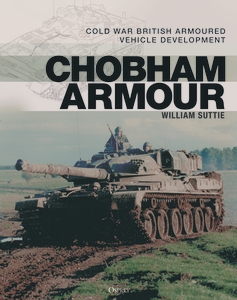

The state of British tank design during World War II and the perceived poor performance of British vehicles compared with contemporary German or Soviet vehicles is often raised in discussions and literature, this despite Britain being the nation that invented and first used tanks. The picture following the end of World War II is somewhat different with British tanks very much world-leading in terms of technology and performance, and forming a key pillar of NATOs defence of Western Europe. Much of the reason for this was the work at the world-class vehicle research and develop establishment on Chobham Common near Chertsey. My book, Chobham Armour, is a review of the development activities carried out there and the resulting military vehicles. Many of the products of what the locals called the ‘Tank Factory’ are well known: Centurion, Chieftain and Challenger tanks, the innovative Scorpion light tank and the FV432 and Warrior work horses of mechanised infantry. Less well-known are the many interesting concepts and prototypes that never made it off the drawing board or beyond the prototype stage. Chobham Armour presents a comprehensive picture of the development work carried out to ensure that the British Army would not be over-matched by the Warsaw Pact forces they faced. As well as the story of how vehicles were developed, a focus is placed on the evolving Army requirements that shaped the designs. Although never used in their main intended role, many of the vehicles developed at the Chertsey establishment proved their worth in conflicts around the world, crewed by the British Army and the soldiers of many other nations.

My own introduction to tanks came through making Airfix kits as a young boy and then progressing on to the larger, and at the time more exotic, Tamiya kits. Living near to Bournemouth, trips to the Bovington Tank Museum were possible and as well as seeing the tanks there, if I was lucky, I would see armoured vehicles driving along the roads around the camp. Information came from the ‘pocket money’ booklets from the museum, Bellona vehicle data booklets, Purnell’s History of the Second World War books and the range of Osprey books on tanks in the rotating stands in bookshops. Another milestone in my interest in all things tanks was getting the first issue of Military Modeller in 1971.

At that time when my interest in tanks began little did I realise that it would set the course for my career. Following study for a degree in automotive engineering at the Royal Military College of Science, I started working at what was then called the Military Vehicles and Engineering Establishment at Chertsey and I have worked at science and technology organisations within the Ministry of Defence ever since.

I therefore wrote Chobham Armour very much as a ‘tank enthusiast’ for other ‘tank enthusiasts’, but one who had the privilege of working on some of the projects discussed in the book. I have been able to access many of the reports written about the vehicles and their development and speak to others at the site who were involved in the work. Using official information and the recollections of those involved means that I have been able to try to ensure that the story told and information provided is as accurate as possible. I have also tried to find information and pictures that have not been published before.

I find that a trait of like-minded tank enthusiasts is that we are often more interested in the ‘might have beens’, the ideas and concepts that never made it or were overtaken by events, than those that were actually fielded. I hope that readers will find many such interesting examples in Chobham Armour.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment