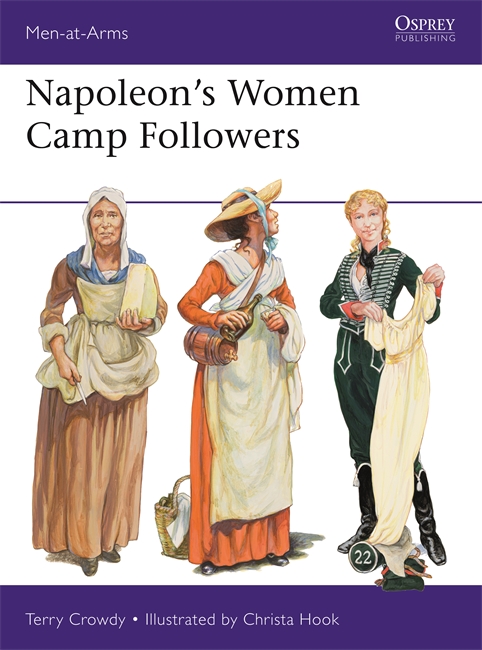

Researched from genuine primary sources in regulations and memoirs, Napoleon's Women Camp Followers is the first book to explain and illustrate the organization, activities and personal stories of the female 'support staff' who played a major role in the day-to-day life of Napoleon's armies. In today's blog post, author Terry Crowdy gives a brief overview of the women and their clothing and explores how these were brought to life on the page.

Napoleon’s ‘Grande Armée’: what is left to say? How about a book on the women camp followers or cantinières who were an integral part of Napoleon’s armies? I thought this book was needed, and so did veteran editor, Martin Windrow, but! … what we were proposing was a Men-At-Arms title, not about men, not about arms, not even about women combatants, but the civilian wives of Napoleon’s soldiers. It was a challenging pitch, but its validity in this series is not as spurious as it might first seem.

Women have always followed armies in one guise or the other, but what was new in the 1790s was the formal licensing of women as regimental sutlers and laundresses. Before this, only soldiers (by definition males) provided sutler services, selling life’s little necessities and occasional luxuries which military rations did not provide. It was a lucrative perk for the soldier, more so because he could afford to keep a wife, and she would do all the work for him. During the 1790s, Napoleon’s armies saw the licensing of women in their own name.

Thousands of sutler-women (and their children) served Napoleon’s armies and were a frequent sight when a regiment marched by. They were seen on the battlefield too, sometimes following their battalion into action, distributing brandy, telling the soldiers they could pay for the drink tomorrow (if they survived). Such examples gave them a certain reputation for courage and compassion. Often the daughters of soldiers themselves, many had grown up following the regiment and could be as tough, resilient, and foul-mouthed as any soldier.

Perhaps the most crucial question answered in this new book is what did they wear? Unfortunately, almost every illustration, painting, model, wargame figure produced on the subject in the last 190 years has made an inaccurate interpretation. This is a bold statement, so I will explain.

After the Napoleonic Wars, cantinières began to wear a sort of uniform. We have fantastic photographs from the Crimean War and beyond depicting these plucky women in pelisses and trousers, with military hats and so on. Later artists began to portray Napoleonic sutler-women in a similar style, with military style garments. Crucially, later artists misunderstood the fashion of the Napoleonic era, providing the women with corseted waistlines, a style which only became fashionable in the mid-1820s.

So what did they wear? French Napoleonic sutler-women wore civilian clothing. French fashion underwent a revolution in the 1790s, and like today, what began as haute couture for the A-listers and influencers among the Napoleonic glitterati soon filtered its way onto the high street. However, unlike the women festooned with tricolour apparel on the barricades of Les Mis, sutler-women did not even wear cockades in their hats. Why would they? They were not soldiers, nor civil servants. Ordinary women took no part in civic life. To have paraded around with political symbols would have been provocative, and when they did, there were brawls in the street.

Researching their costume was a challenging and interesting piece of work, requiring a detailed study of reliable contemporary artwork and collections. The subject made much more sense to me when I got to grips with (metaphorically) the ‘fichu’ (find out what a fichu is in the book!). I also had to research more about the ‘Directory’ or ‘Empire Line’ style, and why an English earl called ‘Spencer’ ‘ singeing his coattails’ in a fire was also significant. I learned how the French mispronounced the English term ‘riding coat’ and spent hours understanding why an Indian ‘Madras’ fabric was worn in a Creole style (true story: In Louisiana during the Spanish colonial period, a law was passed forcing Creole women of colour to wear a ‘tignon’ (a west African-style headscarf) to mark them out as non-European. The law ultimately backfired because the tignon was thereafter worn with such style and attitude, wealthy white women copied the fashion, which travelled to Europe. By 1814 you see French working women wearing the scarf.)

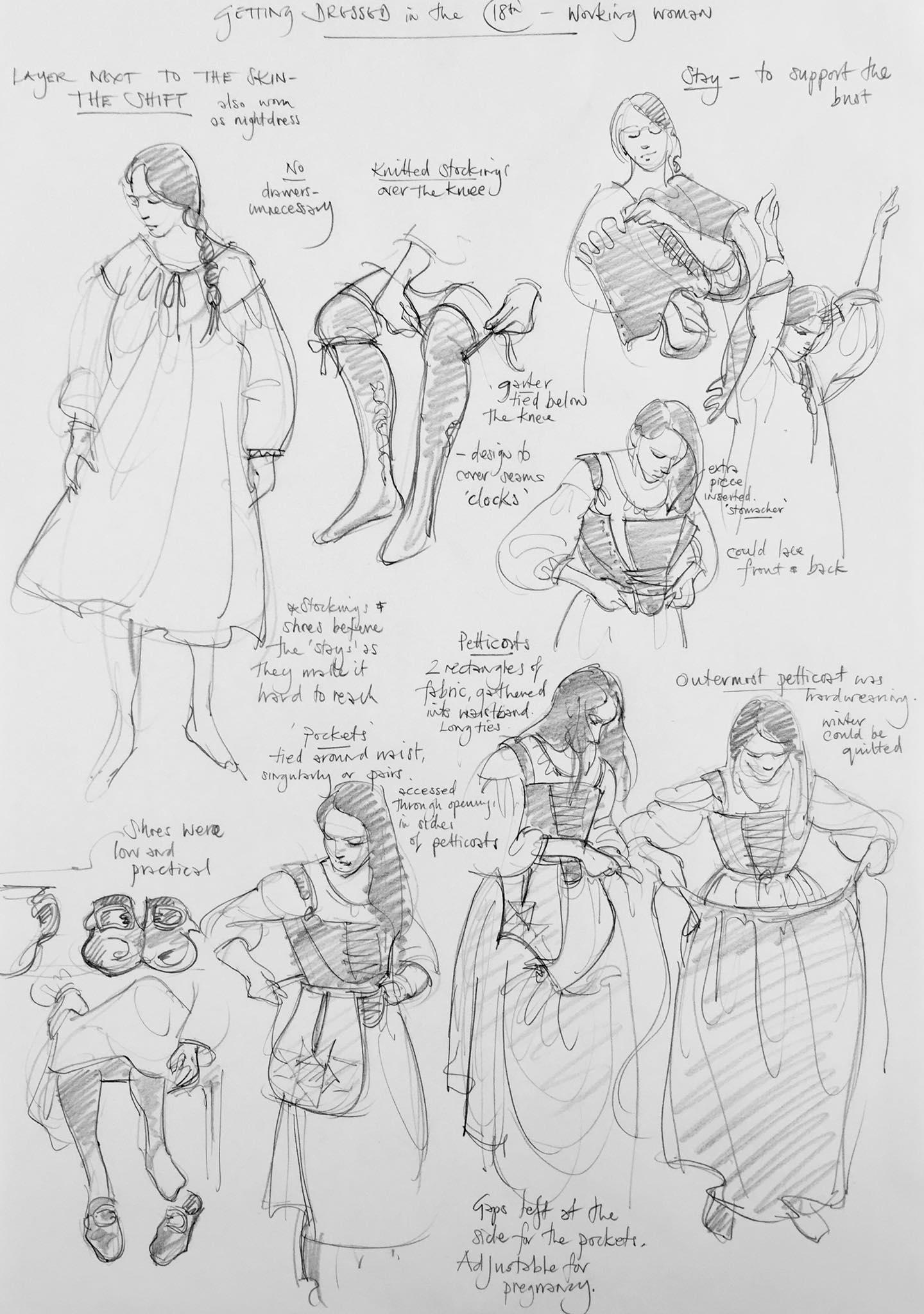

I was lucky to work with Christa Hook on this title. Christa is well-known for her military artwork, but if you follow ‘Christa Hook Watercolour Artist’ on Facebook, you will know how adept Christa is at depicting the female form. This was vital for the project. We had to depict women accurately and naturally. To provide our ladies (as they became known) with an authentic appearance, we had to learn what lay beneath the outer garments, and how the layers of clothing were built up. It was a fascinating process: French women have a certain style and attitude which is as true then as it is today and the French wife of one of Christa’s friends provided clues to this style. Additional research revealed the subtle art of tying the headscarf. As we worked through the first pencil sketches to the final colour plates, it was evident how much Christa enjoyed this project, telling me how connected she felt to each of our ladies, and imagining the lives of the real women who inspired the original artists. Christa was right. More so than with any other project, I found myself forming backstories around each of them.

Christa sketches a woman dressing (preparatory study).

Author Collection

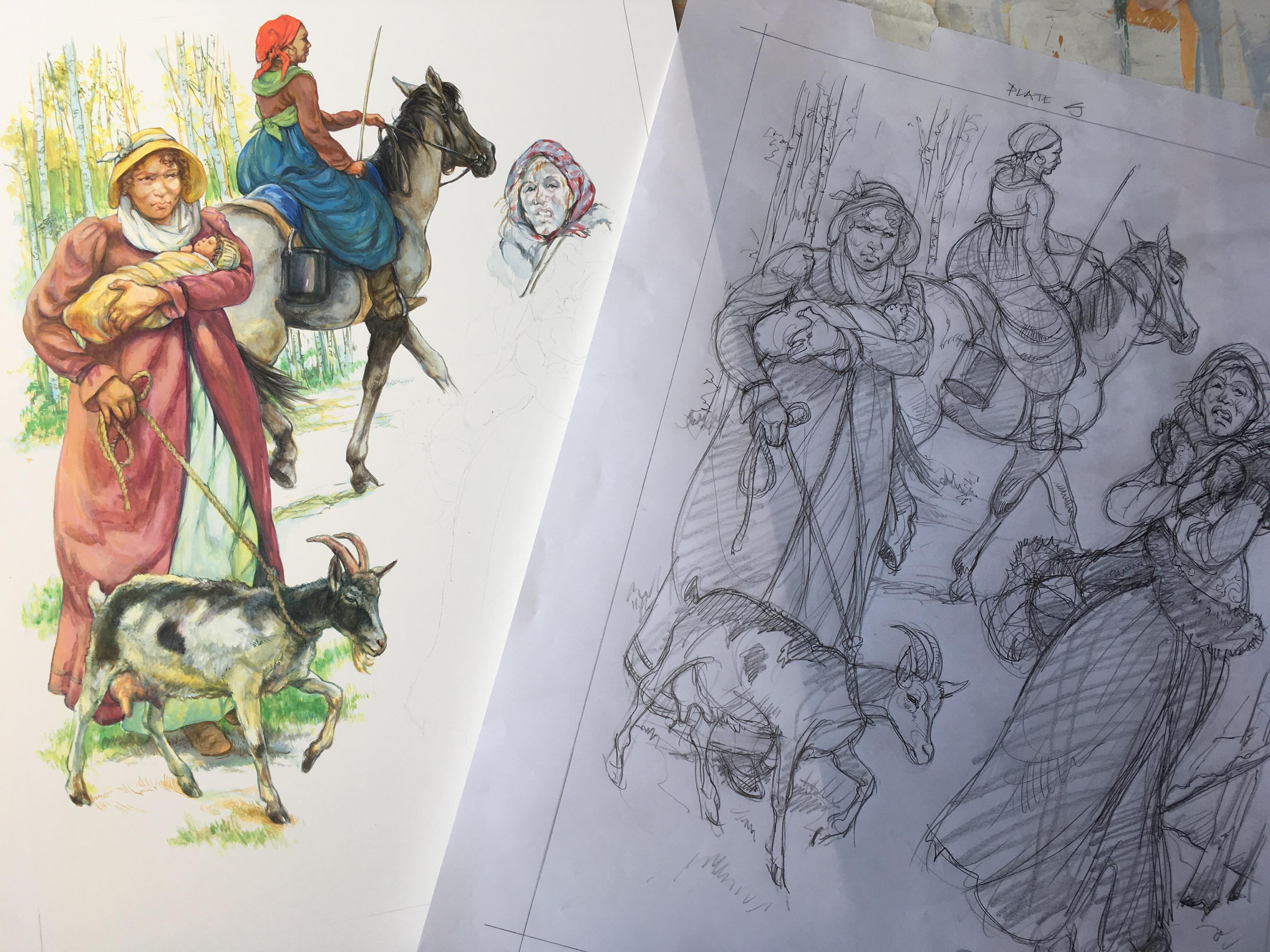

The finished plates are excellent and illustrate the progression in French fashion through the period very well. Even a brief glimpse of the first and final plates will confirm the changes; as will the group of laundresses, each depicting a phase of fashion. My own favourites include a figure taken from Bacler d'Albe’s Passage of the Great St Bernard: the simplicity of the costume is stark compared to its mid-nineteenth century equivalents. The woman on horseback from the 1812 campaign is another favourite: she is taken from Albrecht Adam’s Soldiers on the road to Lianvawitschi and is shown in a military convoy, on horseback, riding astride, with trousers and boots beneath her skirt, and her hair tied in a bandana. Our shared favourite was the French cantinière in Egypt, taken from Lejeune’s The Battle of the Pyramids. Christa has captured the spirit of the woman so well, turning her head while pouring a drink. Modellers prepare!

From pencil to colour plate. Ladies of the 1812 Russian campaign.

Author Collection

There are two pictures in the plates which do not depict sutler-women (or their children). We show one of the Fernig sisters, both of whom were aides-de-camp to General Dumouriez in 1792. I thought their story was worth recording, if only to reinforce the point that women were not allowed to serve in uniform after 1792. The other figure is a camp follower of a different type. Officer’s wives often broke the rules to accompany their husbands, and there is the famous example of ‘Cleopatra’ who smuggled herself on a ship to Egypt dressed as a chasseur à cheval and then ‘came out’ as a woman on arrival in Cairo.

The artist at work. Christa working on the 1814/ 1815 figures.

Author Collection

In conclusion, this fascinating book, brilliantly illustrated, forms an essential pictorial record of the appearance and costume of these unforgettable women with the relevant laws, regulations and context they lived in concisely explained. Forget what you thought you knew, and welcome to the real world of these Napoleonic women.

Napoleon's Women Camp Followers is out now. Order your copy from the website today!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment