On the blog today, Robbie MacNiven, briefly examines the importance of the British Light Infantry in the American Revolution and how they came to be known as "bloodhounds".

For George Washington’s adjutant general Joseph Reed, September 16, 1776 started with musket and rifle fire. The Continental Army officer had been sent forward by his commander early in the morning to ascertain the truth behind reports that British forces, who had recently occupied New York, were on the move once more. Ahead of Reed had gone Knowleton’s Rangers, a picked Continental Army light infantry force consisting of 150 officers and men from Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut.

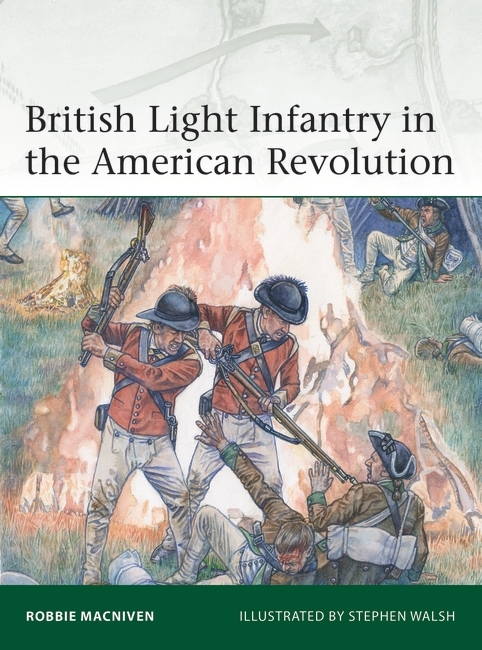

The New Englanders soon realised they had bitten off more than they could chew for, while reports of a massed British advance were incorrect, the rangers had disturbed a piquet force consisting of their counterparts in the British Army – several companies of regulars from the 2nd Light Infantry Battalion, part of Brigadier General Alexander Leslie’s light infantry brigade. Knowlton’s men soon began a fighting withdrawal.

Washington himself arrived on the scene of the developing engagement as the rangers were being forced back, scrambling up a narrow, wooded defile known as the Hollow Way. Reed, who had been observing the combat, rode to Washington’s side intending to recommend that the New Englanders be reinforced. As he did so, he recalled how the British blew hunting horns as though during a fox chase, a fact that filled Reed with particular shame and anger.

Reed’s assumption was probably incorrect. Two other rebel sources that day identified the blowing of horns as signals being sent to scattered British forces to regroup, a far more likely scenario following a brisk woodland skirmish. While Reed may have been mistaken, the metaphor of British hounds hunting down and savaging the wily American fox was not wholly misplaced. Six months after Reed’s experience one British office wrote that hunting rebels was both easier and more enjoyable than a fox chase. Indeed, by late 1777 rebel soldiers were referring to British light infantry specifically as “bloodhounds.” The king’s savage attack dogs were loose in the colonies.

British light infantry proved to be a vital component for Crown Forces during the American Revolutionary War. Indeed, the idea that the British Army was ill-suited to warfare in the Americas is an incorrect one. The experiences of the Seven Years War in both America and Europe had not only acclimatised the British military to warfare on the frontiers of empire, it had also popularised the concept of light infantry, men who were good shots and physically fit, who could act on their own initiative, endure hardship and fight an elusive foe – at that time, Native Americans and French Canadian colonists – in difficult terrain. While budget cuts saw the light infantry disbanded following the conclusion of the war, the experiences of officers and NCOs would go on to inform the British during the Revolutionary War. Indeed, the commander-in-chief in North America between 1775 and 1778, William Howe, had served as an officer in a light infantry battalion during the Seven Years War.

Beginning in 1771, with unrest brewing in the North American colonies, light infantry companies were reintroduced into first the British and then the Irish establishments. In his 1772 treatise Rules and Orders for the Discipline of the Light Infantry Companies in His Majesty’s Army in Ireland, Lieutenant General George Townshend wrote that light infantrymen should be active and able as well as experienced. They were to be, as an officer during the Seven Years War had recommended, accustomed to long marches, at home in woodlands and excellent marksmen. Townshend stressed that victory - and survival - could depend on one well-placed shot.

Pre-war preparations helped to give the British Army a basis to build upon once fighting broke out in 1775. The experiences of Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill acted as a reality check to those who thought the rebelling colonists would be easily subdued. The response was not only to consolidate the strength of the light infantry by forming the disparate companies into composite battalions, but to put the main army at Halifax in 1776 through the basics of light infantry drill. From now on even the regular “line” companies of British regiments would fight in open order and typically engage their enemies with speed and aggression, a far cry from the densely-packed, slow “Prussian” drill that is popularly imagined for British forces of the period.

The immediate result was the battle of Long Island – a victory spearheaded by British light infantry battalions – and the capture of New York. Throughout the following seven years of the conflict, light infantry proved themselves to be the army’s elite in North America, giving British commanders the skill and flexibility needed to engage their enemies in all terrain and circumstances. Their successes were so frequent that the Continental Army mimicked them with their creation of their own light infantry brigades, which went on to win renown at Stony Point and Yorktown.

Just as young officers during the Seven Years War had brought their experiences of irregular warfare into the American Revolution, so young British officers of the Revolutionary War would carry over what they had learned in the later Napoleonic Wars. One such officer, John Moore, became one of the leading advocates for light infantry doctrines, and would play an instrumental part in preparing the British Army for its wars with Napoleonic France.

British Light Infantry in the American Revolution is out now! Get your copy from the website today.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment