Battle of the Atlantic 1942–45, the second of two volumes, explores the climactic events of the Battle of the Atlantic, and reveals how air power - both maritime patrol aircraft and carrier aircraft - ultimately proved to be the Allies' most important weapon in one of the most bitterly fought naval campaigns of World War II. On the blog today, author Mark Lardas looks at some of the advantages the Allies had.

As April 1943 ended, Grossadmiral Karl Dönitz and his U-boats appeared on the cusp of winning the Battle of the Atlantic. His boats sank over half a million tons of Allied shipping in March and a quarter million tons in May. Another quarter-million tons had been damaged over those two months. This deprived the Allies of nearly 200 cargo ships, three-quarters of which were gone forever.

Even if April had been an off month, things were bound to get better. Over 400 U-boats were in commission, with over half operational and attacking the Allies. There had been no day in March and April in which less than 120 U-boats were on combat patrol. On some days over 150 were on patrol. Twenty U-boats were entering service every month, well above the loss rate for the first four months of 1943. By autumn, Dönitz expected to have 200 U-boats on patrol each day.

A month later, Dönitz’s expectation of victory had suddenly been reversed. Instead of the Axis being about to win the Battle of the Atlantic, abruptly the Allies were not only winning, but were on the verge of decisive victory. In May, Nazi Germany lost 44 U-boats, 41 at sea, and had three destroyed in port during a bombing raid. It was an unsustainable loss rate, which led Dönitz to temporarily withdraw his U-boats from the North Atlantic, a withdrawal that became permanent after several attempts to renew the battle yielded further unsustainable losses.

This abrupt reversal of fortune was due to four antisubmarine technologies maturing by the end of April 1943. All were associated with the Allied air campaign against the U-boat: the widespread use of centimeter-wave ASVIII radar, the introduction of the antisubmarine rocket and the Fido acoustic homing torpedo, and finally, the appearance of escort carriers in the North Atlantic.

By the start of 1943, the Germans were aware of the threat airborne radar posed to U-boats, and had introduced countermeasures against them. The most effective was the METOX radar detector. It gave warning when a radar wave reached a U-boat, often before the hunting aircraft realized it had found a U-boat. This gave U-boats time to submerge before it could be attacked.

However METOX only detected the meter waves of the older Mark I and Mark II ASV radars. Centimeter-wave ASV pulses were invisible to METOX. On March 20, enough Coastal Command aircraft were equipped with ASV III that Sir John Slessor, commanding Coastal Command, ordered a new offensive against U-boats crossing the Bay of Biscay. Only two submarines were sunk in the Bay during March and April, but that was because crews were learning how to best use centimeter radar. As May began, they had worked out its idiosyncrasies, and were ready to make use of it.

Coastal Command Wellingtons like this one were becoming equipped with ASV Mk III radar in January 1943.

Author Collection

ASW aircraft also had two new tools with which to kill U-boats as May began. The first was the anti-submarine rocket, a solid-fuel anti-tank rocket modified for use against U-boats. It had been introduced in late winter, 1943. Traveling at near-supersonic speed, with a solid steel warhead, it used kinetic energy to crack open a U-boat’s pressure hull. Each rocket weighed 66 pounds, and eight were carried, four under each wing. Best results were achieved if the rockets were fired at a shallow angle and entered the water. Due to the warhead shape, they arched up, striking the U-boat at or near the waterline.

The second was the Mark 24 torpedo. Air dropped using parachute stabilization, it was an acoustic homing torpedo called Fido. Once in the water, it followed a U-boat’s propeller noise. With a 92lb High Blast Explosive warhead it cracked the U-boa’s pressure hull when it hit. A Fido weighed 680 pounds and could be carried by most antisubmarine aircraft. It had gone into wide-scale production in February and appeared operationally in April.

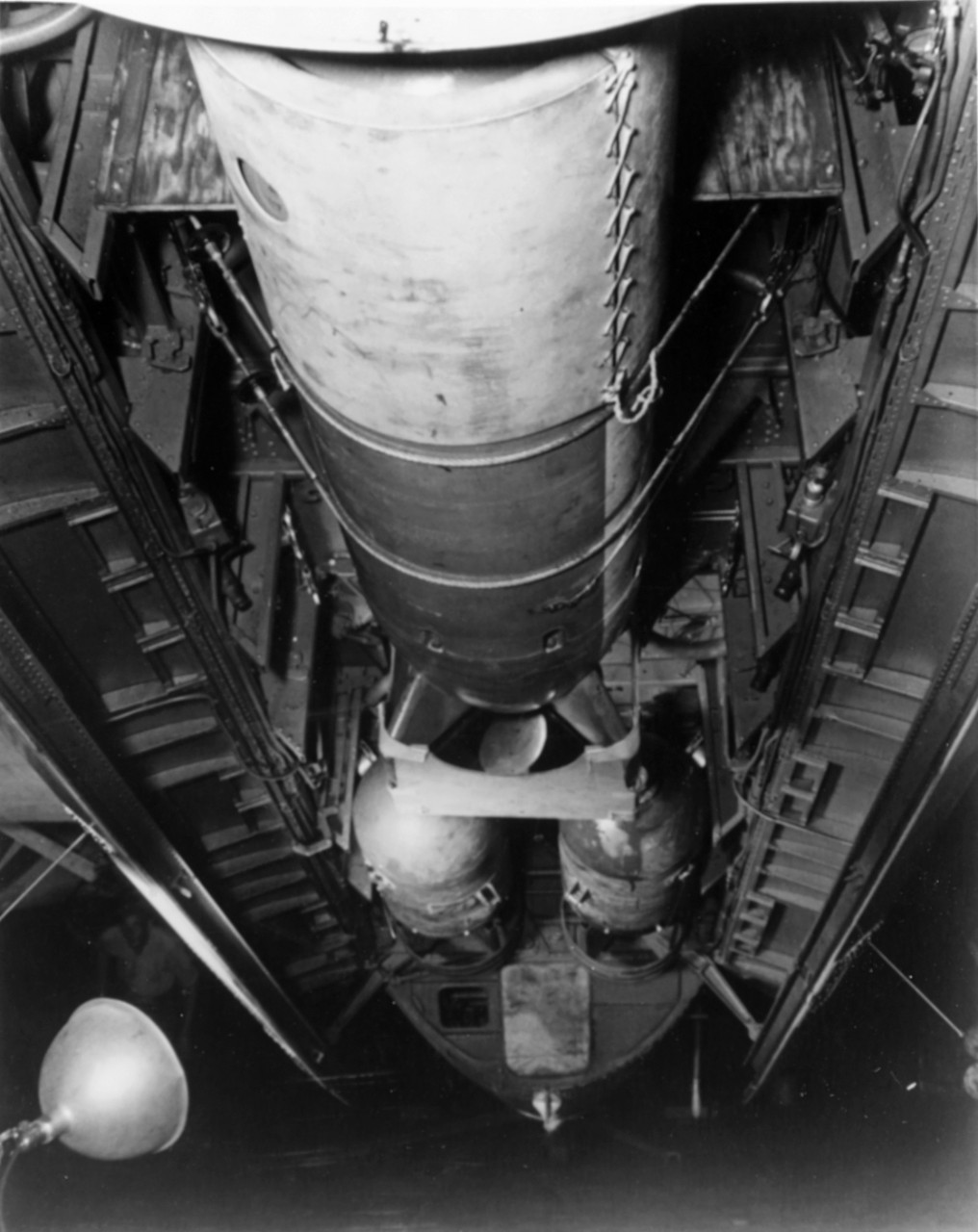

The Mark 24 homing torpedo (or Fido) in the bomb bay of an Avenger. Behind it are two depth charges.

US Navy Heritage and History Command

The final tool was the escort carrier. Escort carriers, twenty-knot vessels usually converted from merchant hulls, had been around since 1941. Due to their scarcity, except for HMS Audacity, sunk in December 1941, escort carriers had not been used to protect routine Atlantic convoys. One had been used on an Arctic convoy in 1942 and several others provided air cover for November 1942’s Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of Northwest Africa. Then in March 1943, two were assigned to cover convoys USS Bogue and HMS Archer. As with centimeter radar, Fido torpedoes, and rockets, there was a learning curve. For the first six weeks they were committed, they achieved no result.

In May, all four factors came together. Coastal Command aircraft equipped with ASV III, and often armed with Fidos began reaping a toll on U-boats crossing the Bay of Biscay, sinking seven. Additionally, the aircraft carriers Archer and Bogue each sank a U-boat in May. Archer’s kill was the first-ever U-boat sunk using rockets. Bogue’s aircraft not only forced U-569 to scuttle, but badly damaged U-231 and U-305. They were the first of many kills racked up by escort carriers in 1943 through 1945.

The escort carrier USS Bogue sank its first of eleven submarines in May 1943.

US Navy Heritage and History Command

Unassisted aircraft sank another 11 patrolling U-boats, and shared credit with warships in sinking another five. Two of those 16 submarines were sunk by Fidos. This increase was due to the greater number of land-based ASW aircraft available, especially very-long range Liberator. Another three U-boat were bombed and sunk in Kiel harbor during an Eighth Air Force raid on that town. In all, aircraft accounted for 25 of the 44 U-boats sunk in May. They also spotted U-boats approaching convoys, directing the escort warships to the U-boats.

Dönitz and his U-boat crews unwittingly contributed to the disaster. In May 1943, Dönitz ordered his crews to remain on the surface and fight it out with ASW aircraft, something that made it easier for the aircraft to sink the U-boats. Also, U-boat crews knew something was wrong when aircraft began attacking U-boats at night, without warning. Two Coastal Command aircrew captured in early 1943 convinced their captors the MEXTOX detectors were the culprit, telling the Germans their aircraft were using transmissions from METOX antennae to locate their targets. This theoretically possible explanation drew attention away from the real cause – the ASV Mark III centimeter radar. It had the side benefit of causing the Germans to discontinue use of METOX, leaving them vulnerable to attack from remaining aircraft with Mark II radar.

Donitz compounded the problem by ordering his U-boats to fight it out with aircraft, adding heavy antiarcraft battiers to some U-boats.

US Navy Heritage and History Command

They may not have realized it, but the Germans were losing the Battle of the Atlantic even before the disastrous May 1943. Allied new construction was outstripping the ability of Germans to sink merchant ships faster than they could be built. ASW aircraft numbers were swelling and tools like Fido allowed aircraft to sink submerged and maneuvering U-boats. Convoy escort warships ordered in 1941 and built in 1942 were finally arriving on the battlefield. But Dönitz’s very bad May underscored the inability of the U-boat arm to attack well-defended convoys or counter the threat aircraft posed to them.

Battle of the Atlantic 1942–45 is out now. Get your copy from the website today!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment