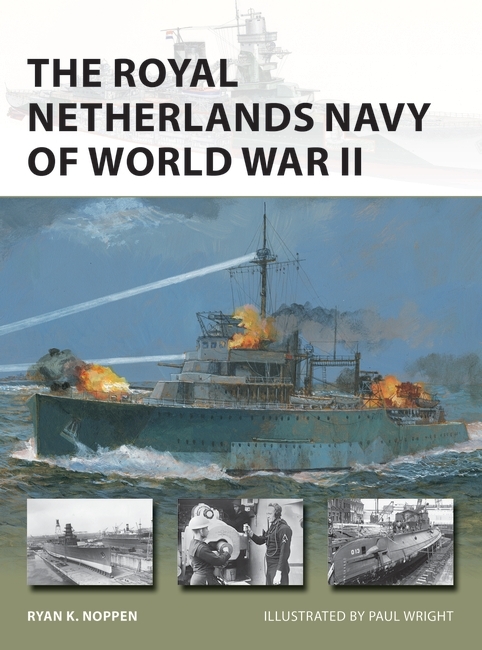

On the blog today, Ryan K. Noppen, author of the new recently released Vanguard title, The Royal Netherlands Navy of World War II, shares how this latest book came about.

If you are familiar with the previous books I have written for Osprey, then you have probably noticed that I tend to write books on subjects that might be considered niche or outside of the mainstream military history interests. One reason for this has to do with my own specialized research and linguistic background while another is my desire to examine subjects that pique my interest which may not be well-covered in the English language. In the case of my most recent book, The Royal Netherlands Navy of World War II, my interest in the subject largely stems from my Dutch heritage.

Growing up in western Michigan in the States as a second-generation Dutch-American, in an ethnic Dutch community, I heard lots of anecdotes and humor regarding the Dutch. I remember my grandfather joking with one of his friends at church (Dutch Reformed of course) who served in the Koninklijke Marine, or Royal Dutch Navy, in the years immediately following the Second World War. My grandfather would ask, “Hey, do you know what the Dutch Navy is?” “Two Dutchman in a rowboat,” was the inevitable punchline. As my grandfather laughed, his friend’s retort was routinely: “Now Carl, de haf some very big scheps.” Some necessary context: my grandfather is an expert at sarcastic humor, a hallmark Dutch trait, but he was also a decorated US Marine Corps veteran of the Korean War (part of the famous Fox Company, or “Frozen Chosen”, which for six days held off a large Communist Chinese force at the Chosin Reservoir in late 1950) and was accustomed to seeing the massive ships and fleets of the United States Navy during his tour of duty. Bearing this humor in mind, why then would I bother to write a book about the “two Dutchman in a rowboat?”

Indeed, the Netherlands is a very small country; by car, roughly two hours across east to west and three hours across north to south. This small country had a disproportionate impact on world history however through its dominance of overseas trade, backed by significant naval power. During the Early Modern period, the Dutch had displaced the Portuguese and Spanish as dominant sea powers and successfully held rising British sea power at bay; I love to remind my British colleagues of the tally of the three Anglo-Dutch Wars of the seventeenth century: one tie and two wins to the Dutch. This seaborne dominance and the establishment of a highly profitable colonial empire during the Golden Age, or Gouden Eeuw, made the Netherlands the wealthiest state per capita for generations. The Dutch were eventually displaced as the world’s preeminent sea power over the course of the eighteenth century by the British; the French occupation of the Netherlands during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars finally broke the back of Dutch naval strength in the Age of Sail. The Dutch colonial empire stayed intact throughout this turbulent period, continuing to bring immense wealth to the home country, but rather than build a powerful new navy to contend with the other great naval powers in the post-Napoleonic world order, Dutch leadership was content to rely upon a foreign policy of strict neutrality and the dominant naval strength of Great Britain through its Pax Britannica to safeguard Dutch interests abroad and on the high seas. To the business-minded Dutch, letting the British bear the massive cost of maintaining peace on the seas was a lucrative decision and the Age of Steam saw the Netherlands maintain a small coastal defense fleet. The “two Dutchman in a rowboat” satire certainly seems apropos here.

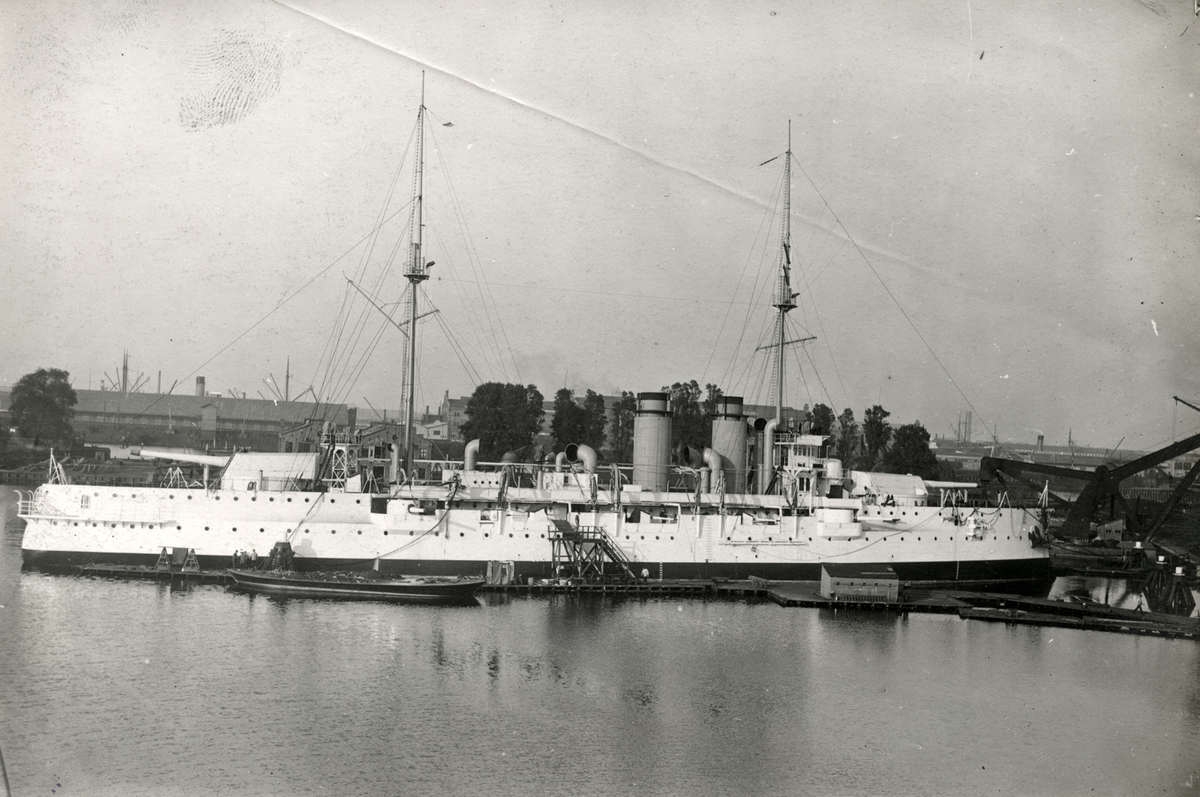

De Zeven Provinciën, launched in 1909, was the largest vessel in the Koninklijke Marine when the First World War began. The culmination of several classes of Pantserschepen, unique Dutch armored ships developed for cost-effective coastal defense in home waters or the East Indies, its armament of only two 280 mm guns and maximum speed of only 16 knots was completely outclassed by the dreadnoughts and battle cruisers entering service with the Imperial Japanese Navy. (collection of the author)

Dramatic events at the beginning of the twentieth century abruptly changed Dutch naval policy and forced the Netherlands to reconsider its position as a minor naval power. First, the events of the Second Anglo-Boer War in South Africa, particularly the imprisonment of Dutch Boer women and children in concentration camps, caused a major rift in Anglo-Dutch relations to the extent that the Koninklijke Marine could no longer view the British Royal Navy as a friendly force. Second, rapid Japanese naval expansion in the wake of the First Sino-Japanese War led to the formation of a new rival naval power in the Far East. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 and the destruction of a significant portion of the Imperial Russian Navy in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 further strengthened Japan’s naval position in Asia. The coastal defense strategy of the nineteenth century could no longer safeguard the sea lanes between the Netherlands and its most profitable colony, the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia) in Southeast Asia nor could it stand up against the Imperial Japanese Navy’s growing battle fleet. On the eve of the First World War, the Koninklijke Marine decided to enter the dreadnought race and submitted design requests with firms across Europe. Then minister van Marine viceadmiraal Jean Jacques Rambonnet created a building plan modelled after German admiral Alfred von Tirpitz’s Risk Theory. A dreadnought design was selected from the Krupp Germaniawerft firm in Kiel and the Koninklijke Marine was in negotiations for construction of five dreadnoughts when the First World War began.

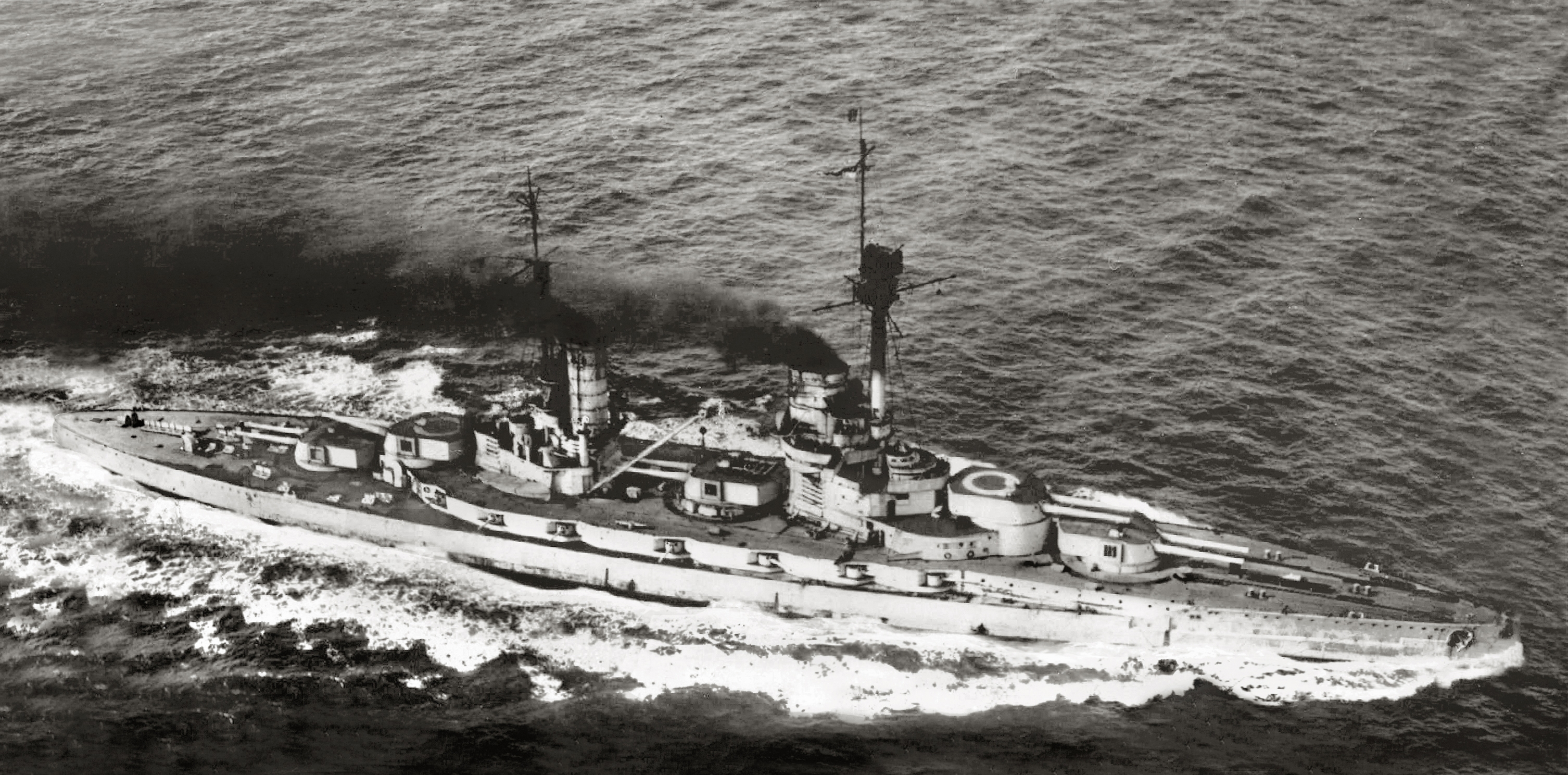

German König class dreadnought underway. The Koninklijke Marine entered into negotiations with the German Krupp Germaniawerft yard for the construction of five similar vessels on the eve of the First World War. (collection of the author)

German wartime demands precluded dreadnought construction for foreign navies and the Koninklijke Marine’s dreadnought program ended at the close of 1914 as Dutch yards were unable to complete such vessels. Rambonnet was unwilling to give up on a Risk Theory strategy and innovatively turned to submarines to fill the place of dreadnoughts. With the aid of Germaniawerft however, the Koninklijke Marine embarked on a vigorous submarine development program during the war. By the time of the Treaty of Versailles and the resumption of peace around the globe however, budget-minded politicians insisted on dramatically scaling back naval construction and the Koninklijke Marine was left with a small force of two cruisers, eight destroyers, and a handful of submarines; hardly a sizeable modern force. The interwar leadership of the Koninklijke Marine, refusing to let go of Rambonnet’s Risk Theory strategy based upon a compact yet powerful surface fleet, railed for new vessels for the defense of the East Indies; the dream of large, powerful warships under the Dutch ensign died hard with many of the navy’s officers. The cash-strapped Dutch governments, particularly during the years of the Great Depression, only gave a trickle of funding which allowed for the construction of destroyers and submarines. The construction of a third modern cruiser, De Ruyter, in the early 1930s caused a great deal of political and popular upheaval; as a result the Koninklijke Marine was forced to agree to a number of cost-savings measures in order to get funding for the vessel approved. Only the rise of Hitler in Germany and the general rearmament taking place across the Continent unlocked funding for substantial new ship construction. Still dreaming back to 1914, the Koninklijke Marine’s leadership pushed for the construction of a modern surface fleet, at the core of which was three new battle cruisers whose design was based upon the German Kriegsmarine’s Scharnhorst class battleships. Negotiations with German builders were still underway in the spring of 1940 when the Wehrmacht launched its surprise invasion of the Netherlands on May 10, 1940.

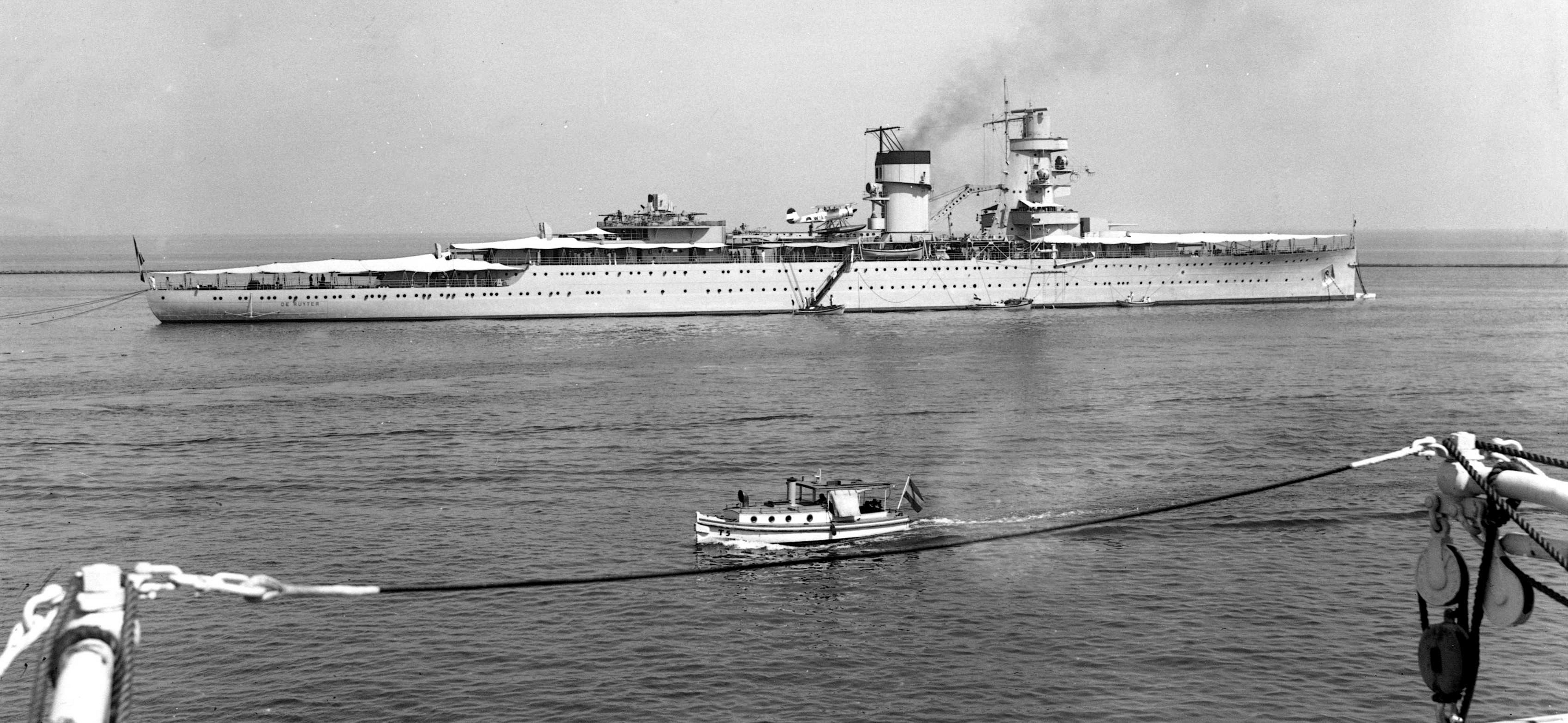

Dutch cruiser De Ruyter, commissioned in 1935. Despite its modern and formidable appearance, resembling the Panzerschiffe of the German Kriegsmarine, De Ruyter’s armament and protection was reduced due to political opposition to the ship’s intended cost and design. The development and construction of De Ruyter serves as a prime example of the obstacles to acquiring a balanced surface fleet faced by the Koninklijke Marine during the interwar years. (collection of the author)

War again (in this case occupation by Germany) brought an end to another ambitious Koninklijke Marine building program. The bulk of the navy’s vessels relocated to the East Indies where they faced the onslaught of Japan’s blitzkrieg across Southeast Asia in early 1942. The small force of three cruisers, eight destroyers, and a number of modern submarines was not sufficient to effectively defend the East Indies archipelago against the vast numerical superiority held by the Imperial Japanese Navy. By the summer of 1942, the Koninklijke Marine was reduced in strength to two modern cruisers, one destroyer, and ten submarines. Although following the Japanese occupation of the East Indies in March 1942, the Koninklijke Marine could no longer effectively operate as an independent entity, its remaining warships and crews, plus two N class destroyers acquired from Great Britain, fought bravely alongside the Allied Navies for the remainder of the Second World War.

By numbers alone, the Koninklijke Marine did not have a large presence in the First World War, interwar years, or Second World War. The service of the majority of its vessels during the Second World War was largely confined to the East Indies Campaign of 1941-42 and is relatively well documented. I cover this campaign in my book but I chose to devote a good portion this new work to exploring why the Koninklijke Marine had the limited number of vessels it possessed by the start of the Second World War. The wrestling of a smaller power, albeit possessing a large colonial footprint, to develop an effective naval construction and operational strategy in the face of two major naval arms races within 25 years fascinated me. Of further interest were the extensive surface fleet expansion plans developed before both World Wars, including designs for dreadnoughts and battlecruisers. Furthermore, in a bit of irony, the German influence upon strategy and warship design also led to the Koninklijke Marine possessing a fleet more similar to that of the Kriegsmarine than those of its later allies, the British Royal Navy or United States Navy. So, with loving apologies to my grandfather, while the size of the Koninklijke Marine was not large during the Second World War, it was certainly more than two Dutchman in a rowboat. Its prewar plans for a larger surface fleets were impressive, albeit controversial, and the initiative shown by the leadership and strategists of the Koninklijke Marine in the first half of the twentieth century, despite being hampered by financial and political constraints, certainly deserves consideration and acknowledgement. I’ve only given the tip of the iceberg here; I hope you enjoy the book. Proost!

The Royal Netherlands Navy of World War II is out now. Preorder your copy now!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment