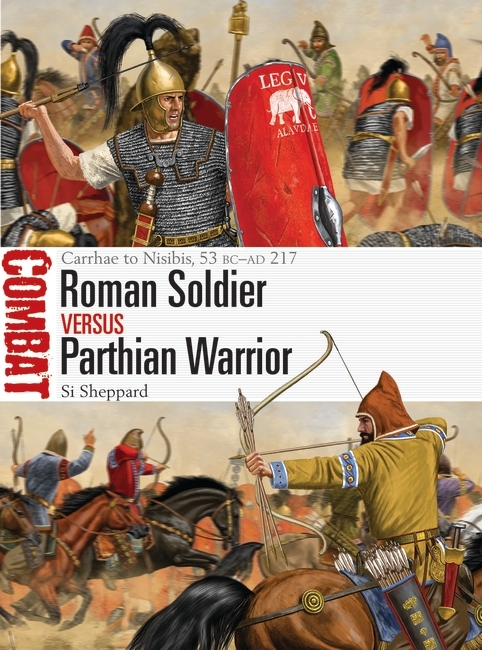

On the blog today, Si Shepphard looks at the concept of the decisive battle, something he explores in his latest Osprey title, Roman Soldier vs Parthian Warrior.

Writing my latest title for Osprey (and my first for Combat), Roman Soldier vs Parthian Warrior: Carrhae to Nisibis, 53 BC-AD 217, allowed me to explore the concept of the decisive battle.

Defining the precise meaning of this term has been the subject of much speculation amongst military professionals, academics, and general students of history. Many books have been written on the topic, but there is no consensus on its definition, or on precisely which battles it applies to. For example, a one-sided outcome does not necessarily make a battle decisive. Hannibal’s great victory over Rome at Cannae (216 BC) is still regarded to this day as the definitive tactical masterpiece in a set-piece battle, but in strategic terms, it was fundamentally indecisive; the war continued, and Rome ultimately triumphed. The battle of Zama (202 BC) could be considered decisive, in that it ended the war, but, much like the equally famous battle of Waterloo (1815), this represented the culmination of an outcome that was effectively inevitable; even had Hannibal carried the day, just like Napoleon, he was confronting, alone, a differential in power that was worsening by the day and would have led to his being run to ground sooner or later. If any battle of the 2nd Punic War was decisive, it was the less-heralded battle of the Metaurus River (207 BC), when Hannibal’s last chance of receiving the reinforcements that could have tipped the balance against Rome in her Italian heartland died with his brother.

Some battles are clearly decisive in that they broke the ability of one side to continue fighting in the war, either by compromising the combat capacity of its army in the field or by undermining the will of its people, at the elite level in the corridors of power or at the street level of popular opinion. Two wars of empire ended in this fashion, with the British defeated by the anticolonial Americans at Yorktown (1781) and the French defeated by the anticolonial Vietnamese at Dien Bien Dhu (1954). Other wars can only be assumed to have experienced not one but a series of turning points; Moscow (1941), El Alamein (1942), and Stalingrad (1942), among others, were the critical markers in the defeat of Hitler during World War II.

Other battles stand out in that they represent the construction of a boundary between one world and another. The empire of Rome experienced two such lessons in the limits of power. The disaster of the Teutoburg Forest (AD 9), when three legions were wiped out in a Germanic ambush, marked the end of Roman expansion into Europe. The imperial frontiers therefore came to rest on the Rhine and Danube rivers to the north, having already reached the immutable geographic limits of the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and the Sahara Desert to the south.

To the east, Rome met her match on 9 June 53 BC, when two worlds collided on a dusty plain outside the town of Carrhae, near the modern-day border of Turkey and Syria. The outcome of the battle that day would reshape the geopolitical map and establish a frontier between East and West that would endure for the next 700 years.

Over the previous three centuries, Rome had crushed all opposition in its inexorable rise to power over the entire Mediterranean basin. No people had been able to resist this restless city-state; not its Italian neighbours, nor the Punic civilization of Carthage, the Celtic tribes of Spain and Gaul, the Macedonian heirs to Alexander III of Macedon (‘the Great’), the Anatolian states of Pontus, or Armenia. When the triumvir Marcus Licinius Crassus – alongside Pompey and Caesar, one of the three men who shared real power in Rome – crossed the Euphrates River, thereby willfully violating Rome’s peace treaty with the Parthian dynasty of Persia, he was entirely confident of expanding this run of unbroken success. Unwittingly, he had initiated a conflict that would endure for generations until it became engrained in the national psyches of both combatants. For Rome had finally encountered a people it could not subdue. Rome’s legions were masters of the battlefield, from the Rhine to the Nile. As infantry, they had no peers. Crassus, however, was stumbling into a trap. For the Parthians refused to fight by the rules as the Romans understood them. The Parthian mode of warfare – their way of life – focused exclusively on the horse. Marching eastwards, the foot-slogging Roman infantry were about to encounter the hard-riding Parthian cavalry galloping to meet them. The outcome was a disaster on an unprecedented scale. In the ensuing clash at Carrhae, Crassus lost everything; the battle; his son, Publius; and his life.

As a direct consequence, the Fertile Crescent would be divided in half, between a Roman west (modern-day Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, Syria and Turkey) and a Persian east (modern-day Kuwait, Iraq, Iran and Azerbaijan) for nearly 700 years. Armenia would always be contested between the two superpowers, and the frontiers would shift incrementally after each war, sometimes in favour of one side, sometimes the other, but always the basic contours would remain the same, until the Arabs, united by the faith of Islam, would sweep the entire chessboard in the 7th Century AD and start a whole new game.

Roman Soldier vs Parthian Warrior is out now. Order your copy now to read more!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment