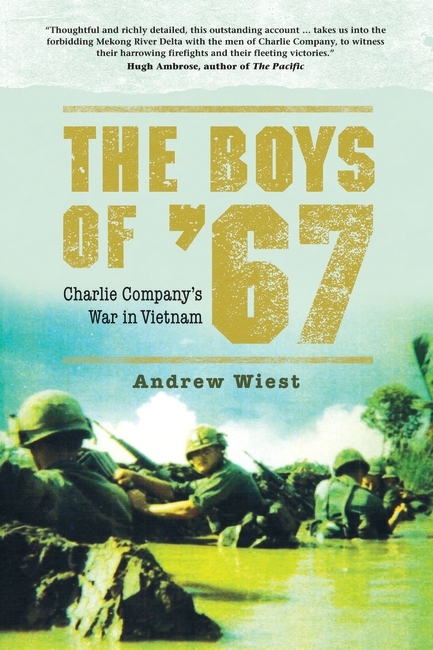

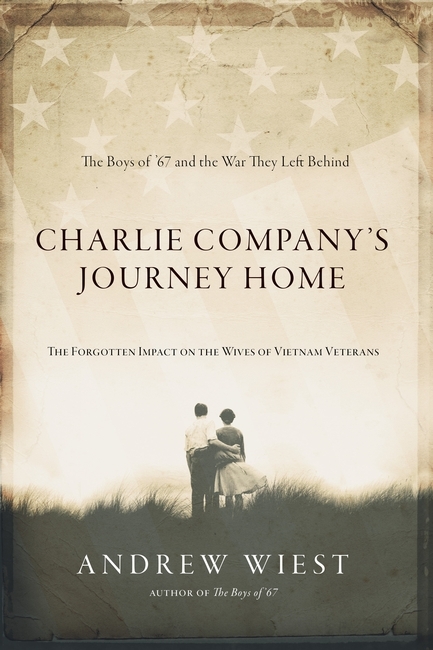

On the blog today, Andrew Wiest answers some of our questions about his latest Osprey books, The Boys of ’67 and Charlie Company’s Journey Home.

.

What initially drew you to the subject of the Vietnam War and the 9th Infantry Division in particular?

I was always fascinated by the Vietnam War – it was the war of my youth. I was 12 when US involvement in the war ended, so I remember seeing it on the television news every night. And it was a war that my older sister’s friends were always talking about, being that they were of draft age. It just seemed to be the war of my generation, so I always wanted to know more about it. But when I went to college to study Military History, nobody taught about Vietnam, so I specialized in World War I. But I kept reading about the war and following its historiography. After I got my job at the University of Southern Mississippi it turned out that they needed somebody to teach about Vietnam, so I volunteered. No better way to have to learn about something than teach it.

In teaching it, I realized that in this war, unlike World War I, I had a huge number of potential veteran speakers who could add to my class. So I began to integrate those veterans into my teaching. I got veterans of all types to come in, from SOG [Studies and Observations Group] operatives, to Marines, to chopper pilots, to nurses, to anti war protestors. Along the way I realized, after reading Born on the 4th of July by Ron Kovic, that a group of veterans that I had missed having in class was veterans who still had issues with the war. So I contacted the Veterans Affairs hospital in nearby Gulfport to arrange a meeting between my students and a group of their patients. As it happens I had been put into touch with the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder clinic at the VA, so we met with three veterans who were suffering from PTSD. Their stories were profound and full of depth and emotion – they affected us all deeply. Of that group of veterans, one stood out, John Young. He was spellbinding and eloquent in a way I could never hope to be. I knew immediately that he had a story that needed to be told. And John was a member of Charlie Company, 4th of the 47th – the unit I studies in The Boys of 67. So it is almost like fate that I came to learn of and tell that particular story.

In The Boys of ’67, you explore many soldier’s stories. Is there one that sticks out to you the most?

Wow. Having to pick one of the stories from Boys of ’67 is like having to choose your favorite child. The stories are all so illustrative of the impact that war has on those young people who are tasked with the fighting. One story, though, that always did stand out was that of Bill Geier. Bill was from Chicago – from the same neighborhood as my father. Bill was older than me by about a decade, but our proximity was clear. We were even at the same baseball games on a couple of occasions. If not for that decade difference, he and I might well have met or served together. Bill became a medic in Charlie Company, and his family was so proud to learn that he would be saving lives, not taking them. He was killed in battle on 19 June 1967, shielding a wounded man with his own body as he tried to save his life. Charlie Company has reunions every other year, and Bill’s family always attends. I had the pleasure of meeting his siblings and his mother. They knew that I was working on a book that included their beloved Bill. They gave me a picture of him and replicas of his dogtags as a thank you – and those still hang above my computer at work to remind me to keep writing and to keep telling the stories of these soldiers. Meeting the Geiers, with whom I am still in regular contact, really lit a fire under me. I knew more than ever that I needed to tell these stories, and to tell them well. There were family members out there relying on me. I couldn’t let them down. So Bill’s story was familiar, it was noble, and it was needed. It hit me in every way.

Charlie Company’s Journey Home focuses on the girlfriends and wives that ‘Boys of ‘67’ left behind at home, and the impact of the war, for good and ill, on the families. Why did you choose to tell this particular story?

In writing Boys of ’67 I interviewed many wives and family members of the veterans, but they occupied a side part of the story – fleshing out the meaning of the veterans’ stories. One of the most memorable characters in The Boys of ’67 is Lieutenant Jack Benedick. The hard charger – the John Wayne that had saved the lives of many men under his command. The larger-than-life figure who lost both legs in Vietnam, but still went on to stay in the army and then become a champion downhill skier. This guy did it all, and became one of the focal points of the book. Jack died from complications of Parkinson’s disease in 2013. In the spring of 2014 Charlie Company gathered at Arlington National Cemetery for the interment – an event so well attended that it became something of a somber reunion. At the hotel I got a chance to sit with Nancy, Jack’s wife, who thanked me for writing about her husband and his bravery. But she also went on to say that for everything Jack had ever accomplished – she and his family had been there pushing him and supporting him. She wondered aloud when someone would ever tell their story. My blindness hit me hard at that point. I hadn’t exactly ignored their stories in Boys of ’67, but I certainly had not told them fully. After returning home I searched everywhere to see how the stories of wives and families of combatants have been told, and found really nothing. Everyone seemed to say that wives and families suffer just as much if not more than the soldiers themselves, but nobody had ever bothered to take that past just being a worn-out saying. Knowing the Charlie Company family as well as I did by that point, it just seemed a natural next step. And it also seemed a great wrong that needed some righting – to finally begin to tell the stories of wives and families at war.

What was your biggest challenge when writing The Boys of ’67 and your latest Osprey title, Charlie Company’s Journey Home

I am a rather typical historian – one who writes perhaps too academically, including zillions of footnotes, in an effort to prove my case. We historians all too often seem mainly to write for only an audience of other historians. I realized that in the Charlie Company stories that I had something much more – a story that needed to be out there in the world, not just on the dusty shelves of academic libraries. The stories I had were spun gold – bravery, sacrifice, trauma, resilience, fear, comedy, camaraderie – it was all there. The stories were deep beyond measure – and I was intensely aware that only I could screw them up. I had been given gold, but I feared that I would produce dross. So I had to ‘de-history’ myself to get to this writing. I wanted to write these books with more of the flow and character development of a novel. So I took to reading science fiction. Those authors conjure up entire worlds and make the readers care about characters who exist only in fictive universes. And I wanted readers to care about the men of Charlie Company. I wanted them to get to know them. I wanted the reader to hurt when Charlie Company hurt. I wanted the reader to mourn when a beloved buddy perished. And to do this, I had to utilize the tools of fiction. I wrote two other books while ‘practicing’ for The Boys of ’67, but still wondered if I had gotten it right. Oddly I started writing somewhat in the middle, with the chapter that includes Charlie Company’s first battle on 15 May 1967. I only allowed one other person to read the chapters in progress, and that was John Young. He had become my confidant and confessor during the whole process. And I was so worried when he read that chapter. I had to send it to him in a manila envelope – rather formally, even though we saw each other nearly every other day. As he read he never let on during our meetings (he would help me teach my Vietnam War class) about his reaction to what he had read. Then one day I got a manila envelope in return. I opened it with a great deal of trepidation. There was the chapter, with nary a word attached. Only a note – that he wouldn’t change a word. The note had an addendum – that the water marks on the pages were from his tears. That was the highest praise I have ever or will ever receive.

What was the most surprising thing you learned when researching your books?

The most surprising thing? Well there were surprises throughout, but I will pick one. Resilience. The men and the families were both incredibly resilient. Both went through things I could only imagine. And yet the men and their families fought on through it all. Women who had children, but who had lost their husbands. Men who returned from war disabled. Men who returned from war unable to put the past behind them. Wives who had been married only for a few months who welcomed home a husband they would never recognize again. Children with no father, or distant fathers. Even those who were most unchanged by war on the surface were still changed. And all of this amidst a country that was trying to forget the Vietnam veterans and their myriad sacrifices. Even with all of these things, Charlie Company veterans and their families prospered. PTSD came along, Agent Orange came along – it all came along. And still these men succeeded, their marriages and families thrived – all to a greater degree than their societal compatriots who had not been to war. What these guys and their families have achieved is nearly miraculous.

How has meeting veterans of the war and their families shaped you and your work?

Becoming part of the Charlie Company family has impacted me deeply. These men and women welcomed me into their midst, not knowing at first what I was going to write about them. They put a great deal of faith into me – something I will never forget. In part because they relied on me and trusted me, I pushed myself as hard as I could to be a better writer. I had to write their stories well, but also write them seriously. The book couldn’t be just for them – it had to be a book that historians and general readers would know to be fully researched and serious. It had to make a contribution beyond simple reporting. Working with these wonderful people in the Charlie Company family has made me a better historian and person. They impact me every day. I have become part of them and they have become part of me.

What subject is your research focusing on currently, and what would you like to explore in future, if you were given unlimited research funding

I grew up in south Mississippi, where there is a strong tradition of service in the military. All around me are veterans – and the ones I know best are National Guard veterans. In America’s wars of the 21st century the National Guard has played a pivotal and vastly under-reported role. In 2005 our local Guard unit served a year-long tour of duty in Iraq, losing 10 killed in action even as Hurricane Katrina levelled their homes. My next writing goal is to use the skills I honed in Boys of ’67 and Charlie Company’s Journey Home to tell the story of our local Mississippi National Guard Unit, the Dixie Sappers, in its 2005 tour. The stories are much the same – of service, camaraderie, and sacrifice. But the book is only a small part of a much bigger project that the Dale Center for the Study of War and Society and the University of Southern Mississippi are undertaking. The National Guard has utterly transformed in the 21st century, with the story of the Dixie Sappers being only a small, illustrative part. From not going to war in Vietnam, the Guard is now a major portion of America’s kinetic military might. Just as a for instance, the Dixie Sappers have undertaken three active deployments – something unheard of in prior generations. This story of the transformation of what the Guard is and how America’s military functions in wartime is sadly very under-researched and under-reported. Part of that problem falls to the nature of the Guard. The National Guard is from every state and territory in the US – meaning that its story is spread out over archives, museums, and armories across the country. There is no central repository for everything Guard. No place for one-stop historical shopping to work on the Guard – leaving its story largely untold. It is our plan at the Dale Center, in tandem with the National Guard Association of the United States, to found a National Center for the Study of the National Guard to serve as custodians of the Guard story. So Charlie Company led me to a desire to tell the story of my Mississippi National Guard neighbors and friends. And that led to the move to gather, chronicle, and tell the story of the Guard written large.

Charlie Company’s Journey Home and The Boys of ’67 are available to order now!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment