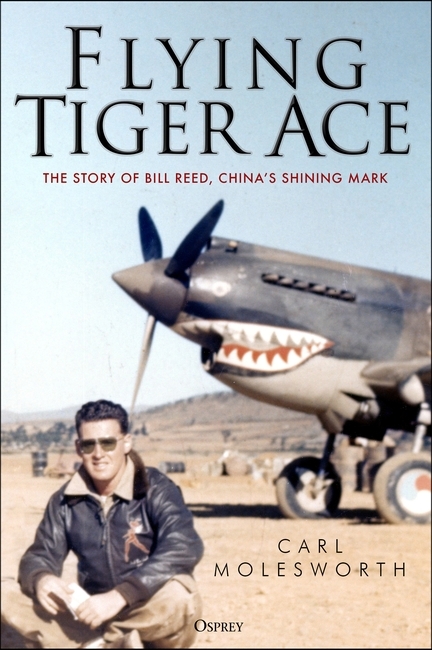

Flying Tiger Ace, The Story of Bill Reed, China’s Shining Mark by Carl Molesworth is a moving biography of Lt Col William Norman Reed, a World War II fighter ace who fought with the Flying Tigers and died in defence of the two nations he loved. In today's blog post, Carl shares a fantastic story about Bill that didn't make it into the book.

It took me many years to work up to the task of writing Flying Tiger Ace, because I wanted to be sure I had enough material to do justice to the story of my subject, Lt. Col. William N. “Bill” Reed. With Bill’s AVG diary plus all my research materials about the Chinese-American Composite Wing from my first book, Wing to Wing, in hand, I knew I could tell readers about Bill’s wartime exploits. But I needed more insight into Bill Reed the man.

Sure, Bill Reed was intelligent, athletic and handsome. That was plain to see. But what kind of person was he? I was pondering this when the Reed family came through with a treasure trove of material in the form of more than 200 letters Bill wrote to his family between 1935, when he left home to attend college, and December 1944, about two weeks before he died in a desperate nighttime parachute jump in China. These not only provided details of Bill’s personal life but also revealed him to have been a decent, honorable and generous human being. I felt like I knew him, even though he died several years before I was born. Then I found out that important stories about Bill’s older brother Kenneth and nephew Major William R. “Dick” Reed merited places in the book as well. Suddenly, I had more than enough material. Something needed to go.

One of my favorite stories about Bill dated from his high-school days, when he and his friends would play pranks on Halloween night. This story was told by his boyhood friend Ed Ferreter in a newspaper article published many years after Bill’s death. I hated to leave it out, but in the final trimming of the manuscript I decided that it was more entertaining than enlightening. I cut the story from the manuscript but kept it for possible use later. Now, thanks to the Osprey blog, I have the chance to share it.

Halloween, 1934

When Old Man Stickney, the part-time town marshal of Marion, Iowa, approached a small knot of teenaged boys standing in the shadows behind the Carnegie Library on 7th Avenue, he knew he had them dead to rights. The time was just past 10 pm, and Mayor John Mullen had ordered a 10 o’clock curfew for this Halloween night of 1934. Someone had been getting into a lot of mischief earlier that evening, and Stickney was pretty sure these guys were the culprits.

Back in those Depression-era days before Halloween became commercialized, boys of a certain age all over America looked forward to October 31 for months in advance, planning pranks they could pull off after darkness fell. It was a night to have some fun, to blow off a little steam. Most Halloween trick-or-treat mischief was relatively harmless. A common trick was “soaping.” The kids would carry bars of soap and rub them on the windows of homes where they were denied a treat, leaving a hazy mess for grown-ups to clean up the following morning. In towns such as Marion, where indoor plumbing was not yet universal, it was not surprising for several outhouses – “privies” in Marion vernacular – to be overturned during the night as well.

Those capers and more had happened in Marion that Halloween evening by the time Stickney accosted his suspects. But the two most elaborate pranks wouldn’t be discovered until the following morning. First, the boys had sneaked over to Mayor John Mullen’s house, where his car was parked outside. Silently, they jacked up the back of the car and placed blocks under the rear axle to leave the back wheels an inch or so off the ground. They could only imagine the mayor’s reaction when he tried to drive the car to work the next day and it wouldn’t go. Then they moved on to their highlight caper of the evening. One of the boys, Ed Ferreter, described it many years later:

“We were just out raising a little clean hell, so to speak. Our biggest coup of the night was getting a cow up on the third floor of the high school. We were careful to tie it securely to a doorknob so it would not ram through the hall or even crash down the stairs. In fact, we even tied it to the principal’s door.”

In typical small-town fashion, news traveled fast in Marion and secrets didn’t last very long. By tomorrow, everyone in Marion High School would be talking about the cow on the third floor, and most of them would know who had put her there. But at this moment, Stickney only knew that windows in most of the downtown businesses were covered with soap and that a stink was beginning to rise from the uncovered cesspools of several overturned privies. He was pretty sure that these boys were to blame, but he hadn’t caught them doing anything except breaking the curfew. All he could do was to turn in their names to Mullen in the morning and let the mayor mete out the punishment later. Even doing this posed a problem for Stickney, however.

Like many Americans of his generation, Stickney had never learned to read or write. So when he pulled a pencil and paper from his jacket pocket, he handed them to one of the boys, Bill Reed, with instructions to write down the names of the gang members and hand the list back to him. It’s possible that Stickney picked Bill for the task because he knew him to be a standout student and athlete at the high school. It’s also possible that Stickney had experienced similar run-ins with Bill’s older brothers, Ed and Kenneth, on Halloween nights past. Whether Bill knew or simply guessed that Stickney was illiterate is not known. In any case, Bill bent to his task and soon produced the list of names. Then the boys dispersed, but not before Bill passed a sly wink to the others. Ed Ferreter tells the rest of the story:

“The next morning Stickney proudly paraded into Mayor John Mullen’s office with his list of culprits. John listened to Old Man Stickney’s complaints. He read the list. Then he said, ‘Are you sure you want to press charges against these boys?’

‘Sure do.’

John picked up the list saying, ‘The first name on the list is your son, Jud Stickney.’

Stickney stuttered, stammered and muttered. He took the list from the mayor, tore it up and stomped out. Jud had not been with us. Bill Reed had outfoxed Old Man Stickney.”

Flying Tiger Ace publishes 20 February 2020. Preorder your copy here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment