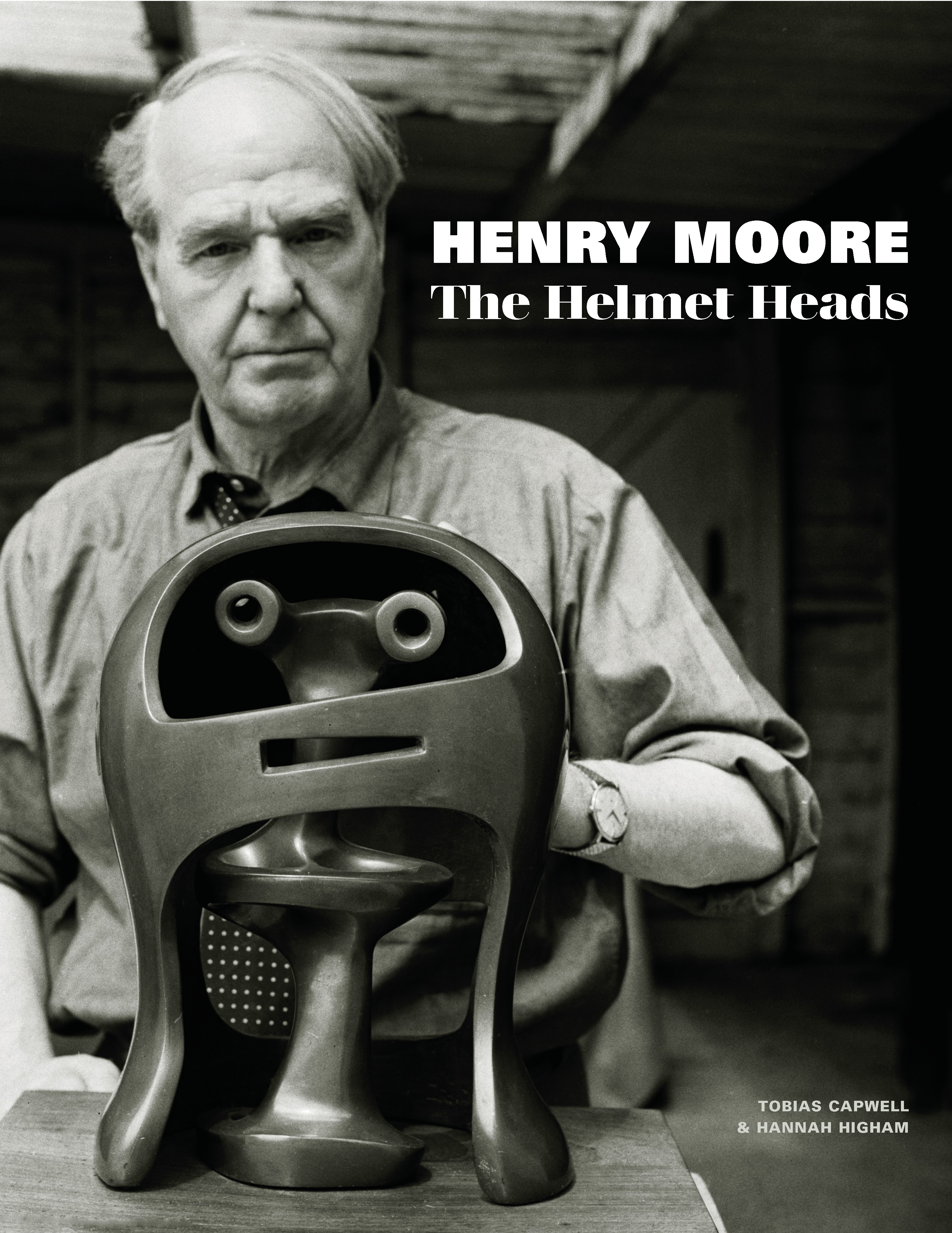

Coinciding with the major exhibition of the same name, Henry Moore: The Helmet Heads traces the footsteps of the artist through the armouries of the Wallace Collection, where he encountered 'objects of power' that profoundly influenced his work for the rest of his career. In this new book, Tobias Capwell, curator of The Wallace Collection, identifies the specific helmets that inspired the artist and examines these alongside Moore's sculptures for the very first time. The reasons for Moore's fascination with armour and the implications it had on his art are explored by Hannah Higham, curator of The Henry Moore Foundation, and set in the context of Moore's life and work. Today's blog post, an extract from the book, gives an interesting introduction to Moore's interest in helmets and the Wallace Collection.

In about 1907 a schoolboy named Henry Moore visited the medieval church of St Oswald, in Methley, West Yorkshire, for the first time. He was profoundly affected by the profusion of stone carving found throughout this magical place. It was the future artist’s first experience of sculpture, as he later explained:

“Methley Church … contains the first real sculptures I remember. I was very impressed by these recumbent effigy figures… [it was] the almost Egyptian stillness of the figure that appealed to me, as well as the hands coming away from the body.”

Two of those effigies represent the late medieval knights Sir Robert Waterton, Constable of Pontefract Castle (d. 1424), and Sir Lionel, Lord Welles KG (killed at the Battle of Towton, 1461). As well as Moore’s first experience of sculpture, Methley was probably also therefore the first time Moore encountered life-sized images of warriors in armour, figures armed for eternity in the accoutrements of war they had worn in life. As a monumental work of funerary art, an armoured effigy was intended to express the identity, the prestige and the power of its subject. Armour augmented its wearer physically, but also changed the way the world saw him. It made him seem superhuman and otherworldly, the glittering steel surfaces reflecting both the light of the sun above and the power of God invested within. When carved in alabaster as at Methley, armour reinforced the viewer’s understanding of and connection to the subject, in order to ask for and spur on prayers for the departed soul.

Even without fully understanding such things, Moore must have felt the power of these images, human forms which also incorporated other, non-human shapes – almost abstract sculptural augmentations of the body inside. Unlike the empty armours which Moore would later contemplate at the Wallace Collection, an effigy is a simultaneous visualization of both the impervious armour outside and the vulnerable human being within. On one level it is a sculpture within a sculpture, while on another it presents us with another quality of armour, the tendency to fuse with the person it protects, creating a living sculpture; armour was a process through which the artist transformed his patron into a work of art. This idea of a form within a form, the kinship between the armour and the wearer, was a constant inhabitant of Moore’s thoughts about armour. As he would elucidate much later:

“The armour idea is this hard covering or shell, to something inside it… And it is like, it’s the same idea as the shell of a crab or a lobster or a snail, protecting a very vulnerable form inside it. It is a fundamental form idea.”

During his combat service in World War I, Henry Moore cannot have failed to see how armour, through its form alone, could project deep feelings and messages. The British ‘Brodie’ helmet, which he wore while fighting as a machine-gunner at the Battle of Cambrai in 1917, was in its basic shape almost entirely unlike the better-designed, more protective and, indeed, more fearsome-looking M1916 helmets worn by the Germans. The fact that Moore did indeed observe the visual and expressive qualities of the helmets of his own time is proven by his incorporation of aspects of the German helmet’s design into Helmet Head No. 1 (1950) and his later Helmet Head lithographs (1974–75).

When he first visited the Wallace Collection during the interwar years, Moore had been well prepared to see and understand the armour displayed there for the complex thing that it was – utilitarian equipment designed for fighting which somehow transcended its function to become, at the same time, expressive art of great power. He seems to have sensed this naturally, effortlessly. He could see perfectly well that the form of an Italian Renaissance helmet was determined by the functional demands informing its design, and yet it is clearly much more than an answer to the physical problem of how best to protect the human head.

Courtesy of The Wallace Collection.

A tool which is designed to function well naturally becomes beautiful. Initially this occurs almost as a side effect. The makers, however, especially those who self-identified as artists first and engineers second, as Renaissance armourers usually did, could perceive this process in action as they worked, and often sought to extend and augment the aesthetic qualities of their creations beyond the requirements of the practical application. An Italian helmet naturally became, as described by Stephen Grancsay, a ‘sculpture in steel’.3 However, for many visitors to the Wallace Collection armouries, the pure sculptural qualities of armour, beyond function and indeed decoration, can be difficult to see. The modern mind often has trouble with the idea that an object can be at once a functional tool and an expressive, even abstract, work of art.

Henry Moore saw it. It is quite remarkable how we can follow him through the galleries, tracing the pieces which most captivated him through their presence in his work on the helmet theme. He spent hours studying particular artefacts, while largely ignoring many others. What did these special pieces, which have lain unmoved since 1908, say to him? What did they make him think about? What did he see in them?

I hope that this exhibition will move its visitors to look at armour in a new way, with a great modern sculptor as our guide.

-Tobias Capwell

To find out more about Henry Moore, order your copy of Henry Moore: The Helmet Heads.

Plus, from now till 23 June 2019, visit the Henry Moore: The Helmet Heads exhibition to explore the great twentieth-century British sculptor’s fascination with armour. Presented in collaboration with the Henry Moore Foundation, the exhibition uncovers the previously unknown role of specific helmets and armour from the Wallace Collection in influencing Moore’s ideas and creations. This is the first time that Moore’s helmet-related works, comprising over sixty sketches, drawings, maquettes and full-sized sculptures in plaster, lead and bronze, have been comprehensively assembled, to be juxtaposed with the Renaissance armour that inspired them. Head to their website to find out more about the exhibition and to book your tickets.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment