On the blog today, Armies of the Great Northern War 1700 –1720 author Gabriele Esposito, briefly looks at the main countries involved in the war.

The Great Northern War was the largest and most important military conflict ever fought in the Baltic region: it saw the heavy involvement of all the states located in northern and eastern Europe, lasting for two decades. At the beginning of the new century, after the many wars that had followed the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, Europe was in search of a new political asset: almost simultaneously with the Great Northern War, in fact, the countries of central and southern Europe were ravaged by the long and terrible War of the Spanish Succession. Both these conflicts had enduring consequences on the future history of the states that fought them. Regarding the Great Northern War, it is important to notice that it marked the promotion of Russia as a real ‘great power’ of Europe; until the ascendancy of Peter the Great, Russia had remained a minor player in the political scene of eastern Europe. The hard lessons learned during the Great Northern War and the consequent ‘Westernization’ of the state realized by Peter the Great transformed Russia into the dominant military power of the Baltic area.

In 1700, when the conflict began, Sweden was one of the great European powers and controlled most of northern Europe. Thanks to the great military victories of Gustavus Adolphus during the Thirty Years’ War, the Scandinavian country had created a real ‘empire’ that comprised large and rich territories. In addition to Finland, which was traditionally a dominion of the Swedish Crown, the Swedish Empire included the following territories: Karelia (a border region between Finland and Russia), Ingria (the coastal region of Russia on the Baltic, where St Petersburg was later founded), Estonia, Livonia (more or less the modern Latvia) and several areas on the northern coast of Germany (Western Pomerania, Wismar, Duchy of Bremen and Verden). The large dimensions of the Swedish possessions meant that they had to be defended from several enemies; after many decades of success, with the beginning of the new century, the Swedes had to face the new Russian menace and a large coalition of old enemies. The latter had contrasting ambitions but shared one important objective: the destruction of the Swedish Empire, in order to expand their areas of influence over former Swedish territories. As we will see, the Swedes were able to achieve many brilliant victories during the Great Northern War and came very near to complete success over all their enemies. In the end, however, the death of their king, Charles XII, and a series of disastrous defeats obliged the Swedes to surrender. Practically all the Swedish territories located outside Scandinavia were occupied by Sweden's enemies, with the result that Sweden became a secondary European power for the decades to come.

Russia and Sweden were the major participants of the Great Northern War, two great military powers that were able to deploy several armies on many different fronts; it is important to remember, however, that the Great Northern War was a large conflict involving many different states. The military coalition guided by Russia included many old enemies of Sweden, first of all the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway. Frederick IV of Denmark had great ambitions for his country, especially regarding dominance over Scandinavia for control of the Baltic commerce. Since the secession of Sweden in 1523, Denmark had always tried to maintain the leadership among the Scandinavian countries. After the Thirty Years’ War, however, Sweden had been able to build an empire and reduce the international influence of Denmark. After 1648 Sweden and Denmark had fought each other in 1657–60 and in the Scanian War of 1675–79; the latter conflict was extremely harsh for both sides but led to no significant political or territorial changes. Many questions remained unsettled betweenSwedenandDenmark, with the result that in 1700 the Danes were ready to side with Russia against their traditional enemy.

Together with Russia and Denmark, the most important enemy of the Swedes was represented by the union of Saxony and Poland: both countries, in fact, were ruled by the same monarch (Augustus II ‘the Strong’). The Electorate of Saxony was one of the most important and powerful German states from a military point of view; since 1694 it was ruled by Augustus II, a monarch who had great ambitions and good personal capabilities. In 1697, after the death of the Polish king John III Sobieski (the saviour of Vienna in 1683), Augustus became also king of Poland. As a result, two of the largest states in eastern Europe came under control of a single monarch. At that time Poland was a ‘commonwealth’ (a sort of confederation) formed by two different states: Poland and Lithuania. Both countries had their own institutions and armies, which were united just by the sacred person of the king. Both Poland and Lithuania, however, were very weak from a political point of view: the real holders of power in Poland were the great nobles, who were extremely jealous of their autonomy and who always tried to limit the absolute power of the king; Lithuania was ravaged during the last years of the 17th century by a cruel civil war between two different factions of nobles. One of the two sides was led by the powerful Sapieha family, who controlled the key positions in the Lithuanian Army. In 1698 the Lithuanian civil war had temporarily ended thanks to a new peace treaty; in 1701, however, the Sapieha family decided to abandon Augustus II and joined Charles XII of Sweden in order to obtain complete control over Lithuania. Augustus hoped to make the Polish-Lithuanian throne hereditary within his family and to use his Saxon military forces to restore order in the Commonwealth (by reducing the power of the local nobles). The outbreak of the war in 1700 prevented him from achieving these internal objectives, something that caused him many troubles during the long conflict. As we will see, the Polish-LithuanianCommonwealthgave a very scarce military contribution to Augustus, who had to rely on his loyal Saxons to continue the long and deadly fight against the Swedes. Poland and Lithuania were the battleground over which most of the Great Northern War was fought, with the Polish and Lithuanian soldiers playing a quite passive role according to circumstances.

Finally, the alliance formed against Sweden was completed by two German states: Prussia and Hanover. The Prussians were still a secondary power at the time, but the participation to the Great Northern War transformed their country into a significant regional power. The Duchy of Prussia originated in 1525 from the former State of the Teutonic Order: in that year the knights became Lutheran Protestants and completely secularized their state. Formally, Prussia was a vassal state of Poland. The Duchy was ruled by the Hohenzollern family, which members already controlled the Margraviate of Brandenburg (a German state centred on Berlin). In 1701 Frederick I Hohenzollern, grandfather of Frederick the Great, elevated Brandenburg-Prussia from Duchy to Kingdom thanks to his alliances with the Holy Roman Empire and Poland. The military reforms that were made during the Great Northern War transformed the Prussian Army into one of the best in Europe, capable to fight in the Baltic area as well as in the War of Spanish Succession. At the outbreak of the Great Northern War, Hanover did not exist: there were, instead, the Duchy of Hanover-Calenberg and the Duchy of Lunenburg-Celle (ruled by two related noble families). In 1705 the two small states were united to form the single Duchy of Hanover, which soon became a significant minor power among the principalities of the Holy Roman Empire. Due to the military support given to the Empire on various occasions, Hanover was transformed into an Electorate in 1708; in 1714 the ruler of Hanover, George Louis, became King of Great Britain after the death of Queen Anne and thus started the personal union between Hanover and Britain. LikePrussia, Hanover joined the coalition formed against Sweden with the ambition to conquer the rich Swedish territories in northern Germany.

Sweden had a few allies to count on: the small Duchy of Holstein-Gottorp (located just south of Denmark, formally a vassal state of the Danish kings but effectively a loyal ally of Sweden) and the Ukrainian Cossacks (organized into a sort of ‘modern’ state, known as ‘Cossack Hetmanate’ or ‘Zaporizhian Host’). In 1649, after bloody and long military campaigns against the Poles, the Cossacks of Ukraine had finally gained their independence and had organized themselves into this new state: very soon, however, the Hetmanate was menaced by the expansionism of Russia. With the ascendancy of Peter the Great, it became clear for the Ukrainians that the vast fields of their country were one of Russia's main expansionist targets. As a result of this situation, Ivan Mazepa (the ‘Hetman’ or supreme guide of the Cossacks) decided to side with Sweden in 1708. Finally, Sweden was briefly allied with the Ottoman Empire during the years 1710–14; like the Cossacks, the Ottomans feared Russian expansionism and wanted to defend their Balkan possessions. These comprised three semi-autonomous states, which were under nominal Ottoman control but that effectively acted as independent countries: the Principality of Moldavia, the Principality of Wallachia and the Crimean Khanate. The two Danubian Principalities covered most of modern Romania and were frequently involved into the major wars that were fought in eastern Europe: the great military clashes between the Turks and the Poles, for example, usually took place on their territory. The Crimean Khanate was the last remnant of the Mongol presence in Russia and Ukraine: after the fall of the Golden Horde during the last decades of the 15th century, Crimea remained in the hands of the Mongols and survived as an independent khanate. In order to resist Polish and Russian expansionism, however, this small tribal state was soon obliged to accept formal Ottoman suzerainty in 1475. The Mongols of Crimea continued to be very active as raiders and slave-traders during the following centuries, obtaining many benefits from Ottoman protection. They were very frequently at war against the Cossacks of Ukraine, who controlled a much larger territory; during the Great Northern War, however, the Tatars (Mongols) of Crimea and the Cossacks fought on the same side.

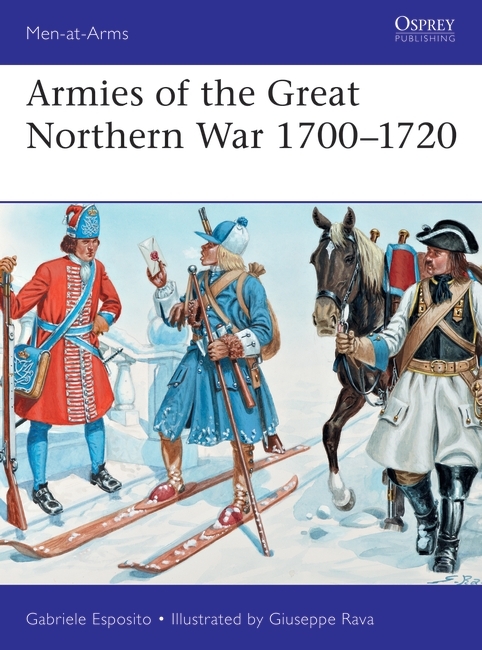

Pre-order your copy of Armies of the Great Northern War 1700 –1720 to find out more.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment