An Englishman Abroad, by Gianluca Barneschi, recounts the incredible true story of Dick Mallaby: spy, Special Operations Executive operative, and the first British agent to be inserted into Italy during World War II. Immediately captured and interrogated by Italian Forces, only his quick thinking and ability to talk himself out of trouble spared him from execution. From that moment on, he was set on a path which saw him become personally involved in some of the most important events in the history of Italy: the Italian Armistice and the escape of the king. The following extract, detailing Dick Mallaby’s first insertion into Italy and immediate capture, comes from ‘Chapter 3: Operation Neck, 14 August 1943‘.

On Friday 13 August 1943, at his Tuscan residence, Cecil Mallaby wrote in his personal diary his impressions of the atrocious heat and the unlucky date.

At the same time, Cecil’s son, the first British agent to begin a mission in Italy, was preparing to lay any superstition to rest and experiencing the tension of the final moments prior to the launch of Operation Neck in similarly hot weather. Mallaby junior had to make his departure dressed as an Italian labourer, on top of which he was also wearing a parachute smock, a jumpsuit and a wetsuit. It took two people (one of whom was Teddy De Haan) to help Mallaby get on board the plane, and even that was a struggle.

At 10.02pm on 13 August, agent Olaf took off from Blida on board a Halifax heading for Italy, piloted by the Canadian Alfred Ruttledge and accompanied by six other crew members. Mallaby was the only passenger on board.

As planned, it was a full moon night.

Despite the tension, Mallaby managed to catch some sleep on the flight to Italy. The aircraft flew over Minorca, south-eastern France and Lodi in Lombardy, and he was woken as it approached Lake Como from the south-west.

The flight was a turbulent one. Due to radar tracking around Nice, as a precaution the pilot dropped chaff; in Italian territory, there was flak in the Savona area and searchlights around Pavia.

The sky was clear and the full moon lit up the landscape described by famous writers such as Byron and Wordsworth. But agent Olaf had no time for poetic musings, and after the customary tap on the shoulder and a ‘Good luck, mate’ from the dispatcher, one Sergeant Wilson, Mallaby launched himself into the black void around 600m above the great Lombard lake. It was 2.48am, 14 August 1943.

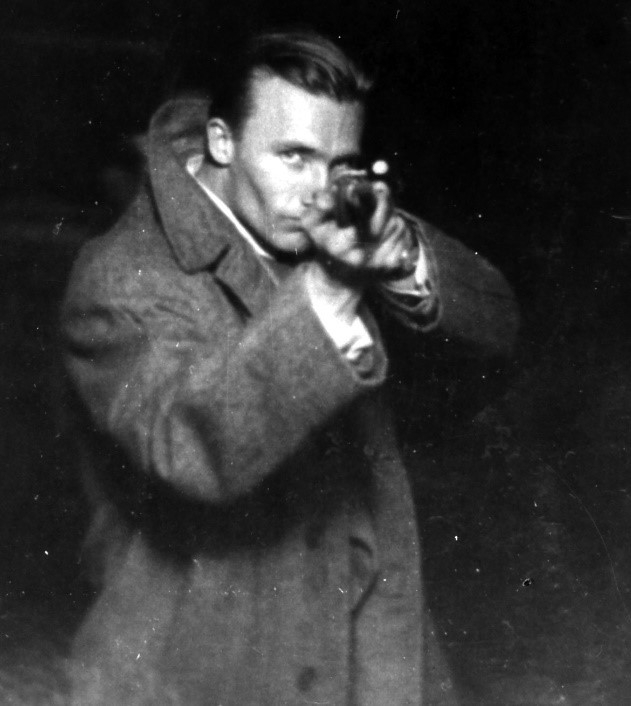

Dick Mallaby in the late 1940s.

Image courtesy of the Mallaby family

The plan was for him to splash down near the town of Torno, about 8km from Como itself, his subsequent destination. Mallaby’s first challenge was to target the central part of the body of water – no easy task, given the narrowness of the lake at this point, and the air currents and micro vortices caused by the surrounding high mountains. Hitting dry land would have been very dangerous.

Dick Mallaby’s parachute opened without problems. According to a subsequent report dated 28 September, ‘The site pre-chosen for the drop was a place where it was highly unlikely anyone would be present after 10.00 p.m.’

As the waters of the lake approached, Mallaby noticed that the banks were not as dark as they should be, and he could see flashes of light to the south.

The report submitted by the pilot who had flown Mallaby to Lake Como was not reassuring, and predicted the forthcoming disaster. It stated that agent Olaf had exited the plane flying at about 200km/h, and that the planned drop point was unsuitable due to the height of the surrounding mountains. Furthermore, it noted the unexpected presence of lights on the ground below and on the surrounding mountainsides. The report ended by reiterating, with fatal foreboding, that despite it being night, the villages around the lake were all lit up.

To the south of Lake Como, a sinister light was spreading from the direction of Milan, which had been heavily bombed the previous night and was still burning. In the hours preceding Mallaby’s jump, thousands of people had also fled to Lake Como: the surrounding area, despite it being night, was busy and brightly lit. Furthermore, the Italian anti-aircraft defences had been placed on alert.

Thus the British agent was spotted while still flying about 1km from the southern shore and 3km to the east of the intended drop point.

Dick Mallaby hit the water safely.

After a brief, dangerous struggle to rid himself of his parachute, his next step was to activate the self-inflating mechanism on his rubber dinghy. Having clambered on board, Mallaby tried to orient himself, moving slowly on the lake using a pair of small paddles worn like gloves.

But the noise made by the British plane had raised the alarm. Mallaby, heading towards the western shore of the lake in the direction of Carate Urio, had no idea that he had already been spotted from there.

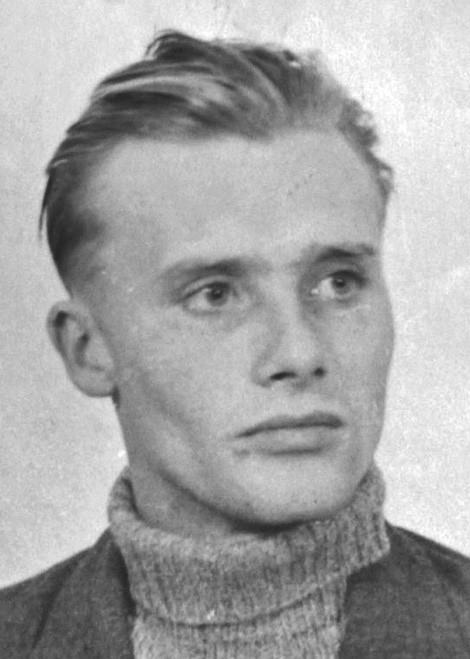

Dick Mallaby’s mugshot.

Image courtesy of the Mallaby family

Using official documents and several eyewitness accounts, it is possible to reconstruct in detail what took place in the hours that followed, and correct several key misconceptions.

Mallaby was first spotted by Domenica Aquilini. From the balcony of her home in Carate Urio, she watched the British agent descend from the sky, and immediately raised the alarm. Also in Carate Urio, Fulvio Borghi and the municipal rural guard Giovanni Abate saw agent Olaf enter the water between Faggeto and Pognana, off the eastern shore of the southwestern branch of the lake. Seeking help, they met local policeman Emilio Rusconi and Amleto Morandotti, a convalescing soldier from the 42nd Genoa Infantry Regiment, and decided to take a rowing boat out to the mysterious parachutist. Another local, Domenico Taroni, also joined the group.

Given the method of transport used, it took some time to make contact with the target, but they were aided by the full moon. Tension grew on both sides. Mallaby heard the sound of hostile voices and saw the flash of torchlights; gunshots followed. Several minutes later, the British agent was intercepted in the middle of the lake around Pognana. From the rowing boat came a shout to halt.

From his dinghy Mallaby replied, ‘Friends!’ Cunningly trying to reverse roles, the best form of defence being attack, he asked with increasing insistence bordering on arrogance if those cautiously approaching him were fishermen.

The rowing boat came nearer, and when he was ordered to put his hands up, Mallaby dawdled, managing to drop the knife he had tied to his wrist into the water. He was soon surrounded by other boats and captured. As he was hoisted on board, Mallaby claimed that he was injured, and was offered a cigarette. Agent Olaf had been captured before his mission had begun.

Want to read more? Pre-order your copy of An Englishman Abroad now!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment