Publishing this month is Tsushuma 1905, which looks at one of the most decisive surface naval battle of the 20th century. Author Mark Lardas looks into the growth of the Japanese navy in today's blog post, and how they came to possess one of the most powerful battlecruisers in the world.

The battlecruiser was a hybrid – an attempt to pair a battleship’s battery with an armored cruiser’s speed and protection. Many believe the battlecruiser emerged in the wake of the dreadnought. In reality, the first attempts at this pairing emerged before the Russo-Japanese War. The first true battlecruiser, a ship with a battleship’s armament on an armored cruiser’s hull started construction during that war.

By the 1890s the standard main battery for a battleship was made up of either 10-inch or 12-inch guns, while armored cruisers typically carried 8-inch or 9-inch main batteries. Both classes of ships mounted large numbers of secondary guns, typically 6-incher, with a tertiary battery of 1-pounder (37mm) or 3-pounder (47mm) quick-firing guns. Naval doctrine called for the tertiary battery to knock out torpedo boats, the secondary battery to suppress fire on the enemy ship to allow a warship to close on its opponent and the main battery to deliver the knockout blows once an enemy ship could no longer fire. By 1904 this doctrine was obsolete, but neither navy realized this until they actually went into combat.

The battlecruiser initially arose from this doctrine. Every navy wanted a fast ship with a heavy battery. It would depend upon speed for safety, its secondary guns would suppress enemy fire while its heavy battery allowed it to deliver a knockout blow quickly.

Two realities interfered with this vision. The first problem was that due to improvements in marine propulsion “fast” changed quickly – often faster than ships could be built. Frequently a ship with record-breaking speeds when it entered service became slower than newly launched warships considered to possess average speeds within five years.

The other problem was the old “pick any two” snag. This expressed itself in several ways familiar to engineers: you could have it good, fast, and cheap – pick any two. More relevant to naval architecture, you could have it heavily armed, heavily protected, and fast – pick any two. Guns and armor required increasing weight as they increased in size. Speed required more propulsion machinery as it increased, requiring greater weight of machinery.

As weight increased, the power required to maintain a desired speed also increased requiring yet more machinery, requiring yet more weight. If you wanted high speed and heavy guns you had to sacrifice armor. If you wanted a fast warship with a battleship’s main guns, it almost required an armored cruiser’s armor.

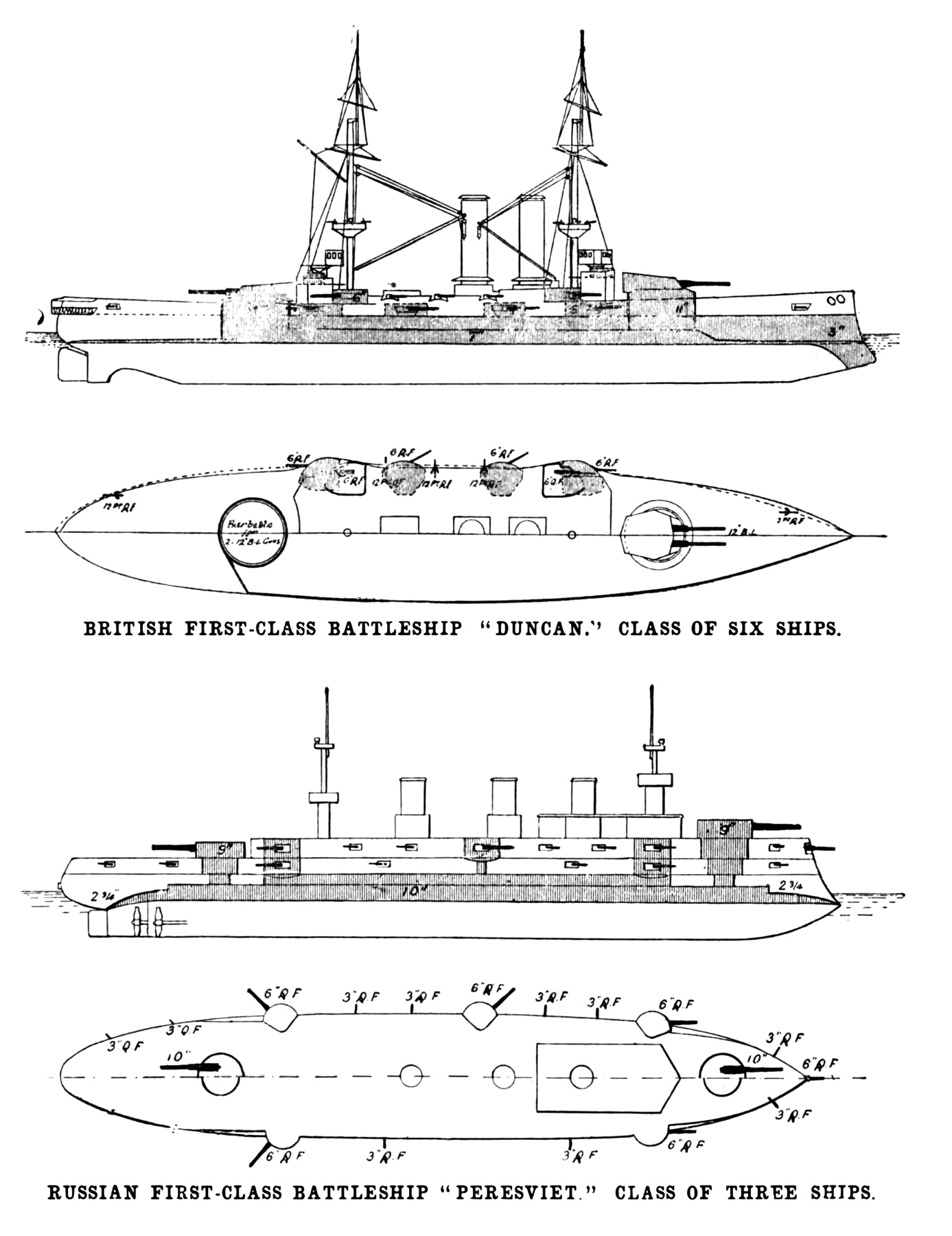

Peresvet's armor compared to the more tradition battleship HMS Duncan

Peresvet's armor compared to the more tradition battleship HMS Duncan

(Source: Author's Collection)

Russia tried to square that circle before the Russo-Japanese War with the Peresvet-class, ordered in 1895. Originally described as “cruiser-battleships,” these vessels were two knots faster than the previous Poltava-class of Russian battleships, despite a displacement one-sixth greater than the Poltavas. This was due in part to a change in engine technology. The Peresvets were the first Russian battleship to use water tube boilers (which ran water-filled tubes through the firebox) rather than the older, less efficient fire tube boilers (which ran heated air in tubes through the water-filled boiler) of the Poltavas.

The Russians also used a 10-inch main battery (light by battleship standards) to reduce the weight of the main guns enough to add extra armor. The result remained a compromise. The Peresvets’ armor was lighter than other Russian battleships built before and after them, but was still heavier than the armor typically carried by armored cruisers. By 1904, when the Russo-Japanese War began, the “cruiser” part of their description had been dropped. They were no faster than new construction battleships, and were simply called battleships.

Japan sidled into the battlecruiser race by accident. Chile and Argentina began a warship race in the first years of the twentieth century. Chile bought two new battleships from Britain. Argentina responded, ordering two very heavy armored cruisers from Italy, adding to the four Argentina already had. Britain, fearing two important trading partners might go to war (curbing British trade profits) defused the crisis, buying the two battleships from Chile. This led Argentina to sell off its unneeded cruisers nearing completion as 1903 ended. With war imminent Russia and Japan both attempted to buy the cruisers. British pressure and a better offer by Japan led to Japan winning that battle. The cruisers entered the Imperial Japanese Navy as Kasuga and Nisshin.

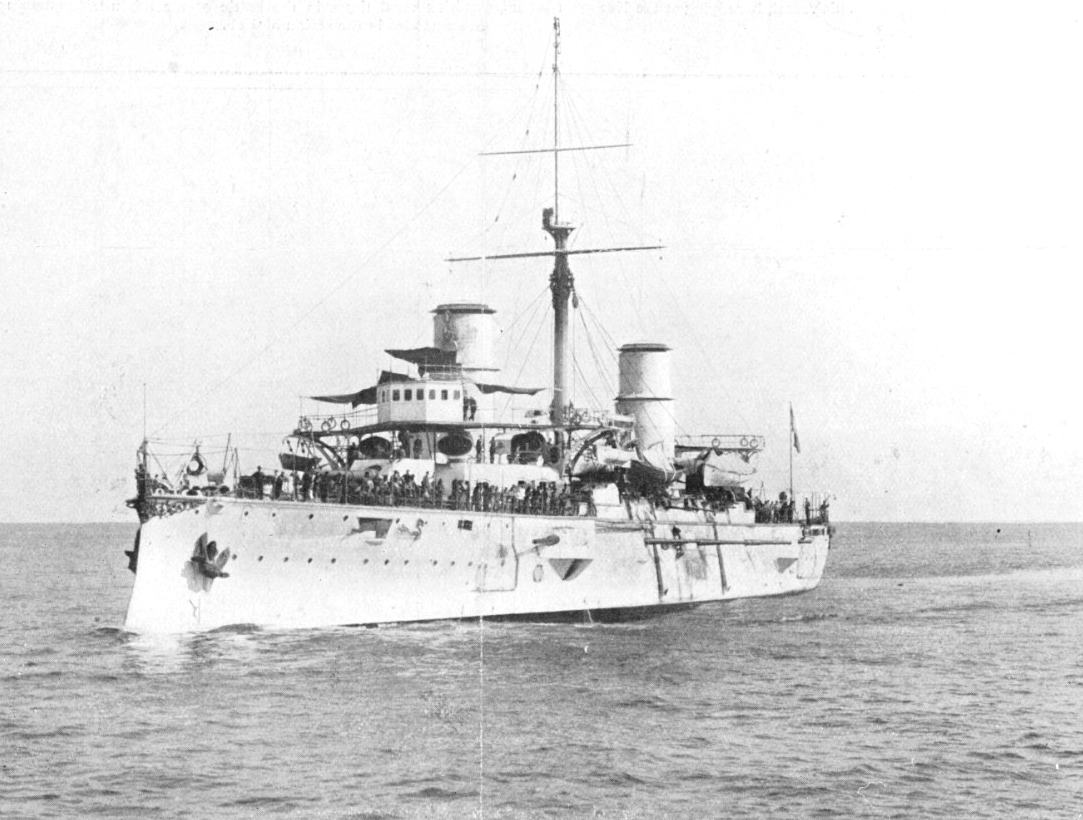

The IJN Kasuga had a 10-inch gun, which could have put it in the category of a battlecruiser.

The IJN Kasuga had a 10-inch gun, which could have put it in the category of a battlecruiser.

(Source: US Navy Heritage and History Command)

The ships were large for armored cruisers, and heavily armored as armored cruisers go. Nisshin had a traditional cruiser main gun suite of four 8-inch guns. Kasuga mounted a single 10-inch gun in its forward turret, giving it a mixed main battery of one 10-inch and two 8-inch guns. If you squinted hard you could sort of, kind of, make a case that Kasuga carried a battleship’s battery (the single 10-inch gun) which made it a battlecruiser. Especially since Japan used the two armored cruisers in their First Battleship Squadron as replacements for Yashima and Hatsuse after those two battleships sank after steaming through a Russian minefield.

However, a single light battleship gun does not transform an armored cruiser, even a large one, into a battle cruiser. Besides, three of the four Argentine armored cruisers that were near-sisters of Kasuga and Nisshin had a main armament of two 10-inch guns. Argentina and the rest of the world considered them armored cruisers.

Japan began construction on two actual battlecruisers during the Russo-Japanese War, almost accidentally. Neither was completed before the war ended. These were Tsukuba and Ikoma.

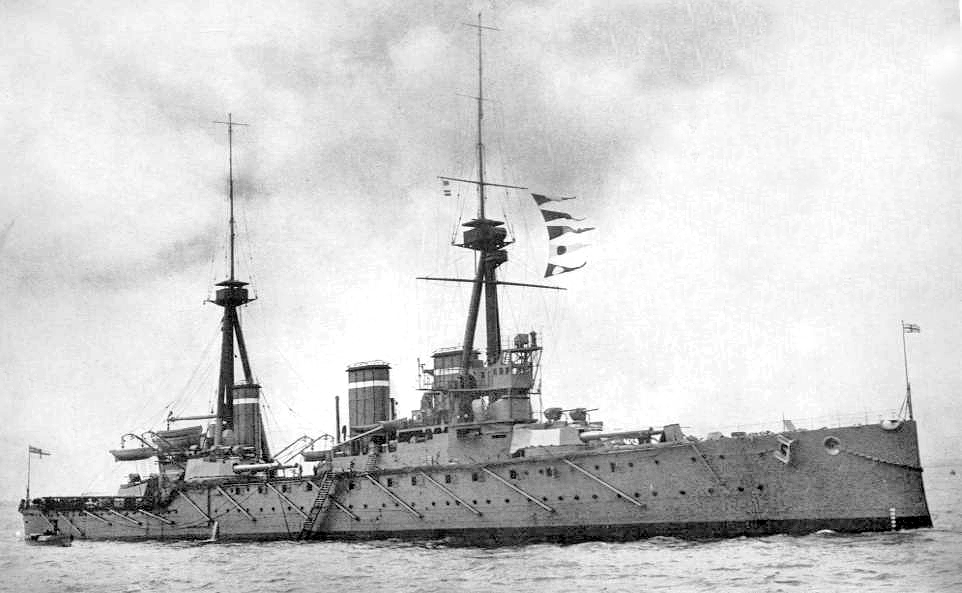

Ikoma, started during the Russo-Japanese war, and carrying a battleship's main battery,

Ikoma, started during the Russo-Japanese war, and carrying a battleship's main battery,

it and its sister Tsukuba were the first battlecruisers

(US Navy Heritage and History Command)

By 1900 Japan was building scout and protected cruisers domestically. Increased experience in shipbuilding gave Japan the confidence to build larger warships, starting in 1904. A special appropriation bill passed that March after the Russo-Japanese War began, authorized construction of four armored cruisers and two battleships in Japanese yards.

The first ships started were two armored cruisers. They were to be large ships, the largest warships built in Japan to that date. Initially they were intended to carry a main battery of four 8-inch guns, the traditional armament for an armored cruiser. Between their authorization of these cruisers in March 1904 and when the first of the two was laid down in January 1905 two events occurred which changed these plans.

The first, in May 1904 was the loss of Yashima and Hatsuse, reducing Japan’s battleships by one-third. It forced use of armored cruisers Kasuga and Nisshin in a division with the remaining four Japanese battleships. They proved less vulnerable to Russian shells than expected.

The second, in August 1904 was the Battle of the Yellow Sea, a protracted all-day action that included nearly four hours when the Japanese and Russian battle fleets traded broadsides. The Russians opened fire at 15,000 yards, with both sides regularly landing hits at 12,000 yards. While Kasuga and Nisshin stood up to the fire well, 12,000 yards was outside the range of the cruisers’ 8-inch guns. They just had to take fire until the battle closed to where those guns could reach the Russians.

Given that armored cruisers had shown they could stand in a line-of-battle against battleships, but that their guns were so badly outranged, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s naval architects came up with a radical design change to Tsukuba and Ikoma. Replace the 8-inch main battery with 12-inch guns. The hulls were big enough. The ships were designed to displace 13,800 tons, only a little smaller than Hatsuse’s 14,800 ton displacement and larger than the 12,230 ton Yashima. Guns were available; space 12-inch guns intended for use on the two sunken battleships.

Tsukuba and Ikoma were redesigned to accommodate four 12-inch guns in twin turrets. The armor was lighter than that of the battleship, but it protected almost as well as the sunken battleships. Tsukuba and Ikoma had Krupp armor, while Yashima and Hatsusa had Harvey armor. Five inches of Krupp armor produced the same protection as 6 1/2 inches of Harvey steel. The cruisers had a top speed of 20.5 knots.

The two ships were rushed through construction. Tsukuba was laid down January 14, 1905 and launched December 26, 1905. By then the war was over, and completion continued at a more leisurely rate. Ikoma was laid down on March 15, 1905, but it would not be launched until April 9, 1906 – construction slowed after it became apparent neither ship could be finished in time for combat. Tsukuba was finally completed in January 1907, while Ikoma did not join the fleet until March 1908.

By then both ships were already obsolescent. In December 1906, five weeks before Tsukuba joined the Imperial Japanese Navy, the Royal Navy commissioned HMS Dreadnought, a new type of battleship that mounted ten 12-inch guns in five twin turrets. It had a broadside of eight guns – equal to both Japanese battlecruisers. Moreover, thanks to its turbine engines, it had a top speed of 21 knots, greater than that of the battlecruisers.

HMS Invincible prior to World War I, the first dreadnought battlecruiser

HMS Invincible prior to World War I, the first dreadnought battlecruiser

(Source: Wikipedia)

In April 1906 the Royal Navy started construction of Invincible, a battlecruiser. Only this battlecruiser was a dreadnought warship. It had four twin 12-inch turrets and could fire a broadside of six. Its turbine engines could drive it at 25.5 knots – 25% faster than the Japanese battlecruisers, with their triple-expansion engines. Regardless, until Invincible was commissioned on March 20, 1909, Japan could boast it had the most powerful battlecruisers in the world.

Tsushima 1905 looks at the pivotol battle of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), and publishes on Thursday 29 November. To pre-order your copy, click here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment