Last month we published Snapdragon: The World War II Exploits of Darby's Ranger and Combat Photographer Phil Stern by Liesl Bradner. This incredible new book showcases the outstanding photographs taken by Phil Stern during his remarkable service during World War II as a combat photographer with Derby's Rangers, and uses Stern's catchy 1940s lingo and humour to transport readers 70 years back in time.

Last month we published Snapdragon: The World War II Exploits of Darby's Ranger and Combat Photographer Phil Stern by Liesl Bradner. This incredible new book showcases the outstanding photographs taken by Phil Stern during his remarkable service during World War II as a combat photographer with Derby's Rangers, and uses Stern's catchy 1940s lingo and humour to transport readers 70 years back in time.

Today on the blog, author Liesl Bradner discusses Phil's entry into the war, his memoir, as well as letting us know which of his photographs is her favourite.

By early December 1941, World War II had been raging in Europe for two years. The British had been busy fighting in North Africa, Norway, and Greece. They had survived the Blitz and the debacle at Dunkirk. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic in the desert town of San Bernardino, California, Phil Stern, a budding photographer from Brooklyn, was on assignment for Popular Photography, to take pictures of the Women’s Ambulance and Defense Corps of America (WADCA).

In the early morning of December 7, Stern was snapping photos of the women reenacting with gas masks on when the field radios blared out, “The Japs have just bombed Pearl Harbor! The West Coast Army Command orders all officers and national guardsmen to report to their post at once!”

Phil hastened back to Los Angeles and immediately enlisted in the US Army. A few months later he was working at 35 Davis Street in London and Allied Headquarters at 20 Grosvenor Square as a Signal Corps Photographer. For a while, London was exciting for a young Yank’s first time across the pond, but boredom soon set in. Taking photos of high level officers and elite society parties wasn’t exactly what he had expected. Where was all the excitement and combat scenes he joined the Army to photograph? He desperately wanted to see some action and fight the Nazis. As luck would have it, Phil came across a notice in Stars and Stripes looking for volunteers to “get nasty with those Nazis – in an elite hit-and-run unit.” After getting the okay from his boss, Major Cuthbertson, Phil hopped on a train to Corker Hill in the Scottish Highlands, where he would train with the British Commandos. After meeting with Colonel Darby, the charismatic leader of the 1st Ranger Battalion, Phil would not only be designated as Darby’s Rangers official photographer but would also train and fight alongside the men as a bona-fide member of the elite army unit in North Africa, Tunisia and Sicily. He was given the nickname “Snapdragon” by one of his fellow Rangers. Now, if he could just figure out how to shoot a rifle.

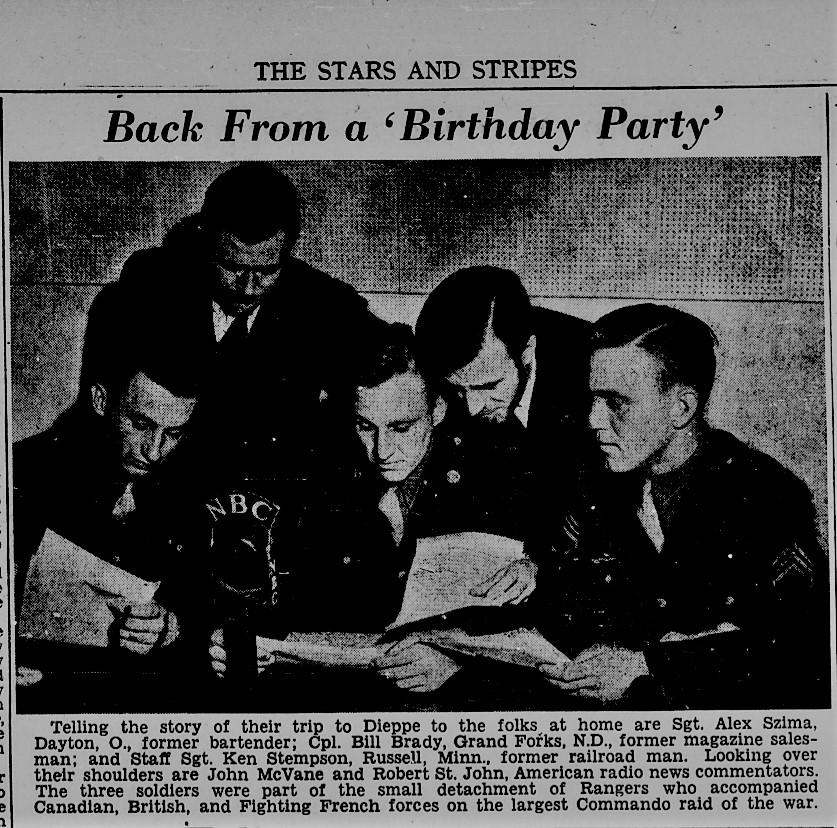

The moonfaced, stocky snapper would also capture rare photos of three of the 50 rangers that fought alongside the Canadians and British in the Dieppe Raid on August 19, 1942. Little has been known about the Rangers’ top-secret first raid, codenamed Operation Jubilee. Three Rangers were KIA in the raid in Northern France. They would be the first American casualties in Europe during the war.

Jumping ahead to 2011, I was assigned by my editor at the Los Angeles Times to interview Phil. I meet the 92-year-old Stern for the first time at his Hollywood bungalow home across the street from Paramount Studios. He had recently opened his own art gallery in Downtown Los Angeles and was exhibiting his collection of John Wayne photographs. Although politically the two were polar opposites, they remained friends until “The Duke’s” death on June 12, 1979.

During this time, I began researching and learning about Darby’s Rangers and Phil’s time in the US Army. (I’m a big history enthusiast.) I stayed in touch with Phil and his family, writing articles about his photos of Marilyn Monroe and Frank Sinatra, and his service in the war.

D-day in New York City (Phil returned to the US in Oct. 1943 after being wounded in N. Africa & Sicily)

D-day in New York City (Phil returned to the US in Oct. 1943 after being wounded in N. Africa & Sicily)

In 2013, Phil and his family were invited to Sicily for the 70th anniversary of the invasion of Sicily. It was his first time back since the war. After returning home to Los Angeles, I met up with him again for an interview for WWII Magazine. He seemed different – a little more cranky than usual. Seventy-year-old memories, previously hidden away in the dark recesses of his mind, had resurfaced. He shared difficult, painful stories about some ugly fighting in Sicily which he’d bottled up for decades. Two documentaries were filmed while in Sicily about his time there during the war. In 2017 The Phil Stern Pavilion, a permanent exhibit of his wartime photographs, was built in Catania, Sicily.

In early 2014, I got a call from the 94-year-old and his son Peter. Phil was moving into the newly built Veterans Home in West Los Angeles and wanted to donate 100 of his photographs to adorn the empty white walls. He asked me if I would spearhead an exhibit of his photos coinciding with his 95th birthday bash. While digging through his vast archives I came across a tattered, 77-page unfinished manuscript circa 1944. I immediately scanned the crumbling, yellowing pages and quickly read his incredible tales. His writing stopped after Kasserine Pass. Captivated by his fascinating stories, I wanted more, so I gave him a call. “Why didn’t you finish and get this published?”

After returning home to the US to recuperate from his injuries in El Guettar and Sicily, Phil was recruited by Uncle Sam to go on a cross-country bond tour. Afterwards, he soon got busy working in Hollywood and raising a big family. At one point actor Gary Cooper and director Fritz Lang expressed interest in a movie version of his manuscript, due to the popularity of war films at the time. Like many movies, Phil’s story, “Ranger’s Return,” never got made. The manuscript languished in a folio box for nearly 70 years.

Then, one day in November 2014, I got a voicemail from Phil. He was on a rant. He’d been reading Killing Patton, and wanted to straighten things out. Decades after General Patton’s death, Old Blood and Guts still put Phil in a fit. He’d had some run-ins with the colorful General in North Africa. “The S.O.B. caught me on the rear lines in Tunisia without a helmet and fined me 25 bucks and a night in the slammer!” His tirade continued. “This guy O’Reilly doesn’t know what the hell he’s talking about!” Phil proposed we write a book on his version of General Patton. “What about your memoirs?” I asked. “Oh, yes, get that published too,” he said.

Favorite Photo

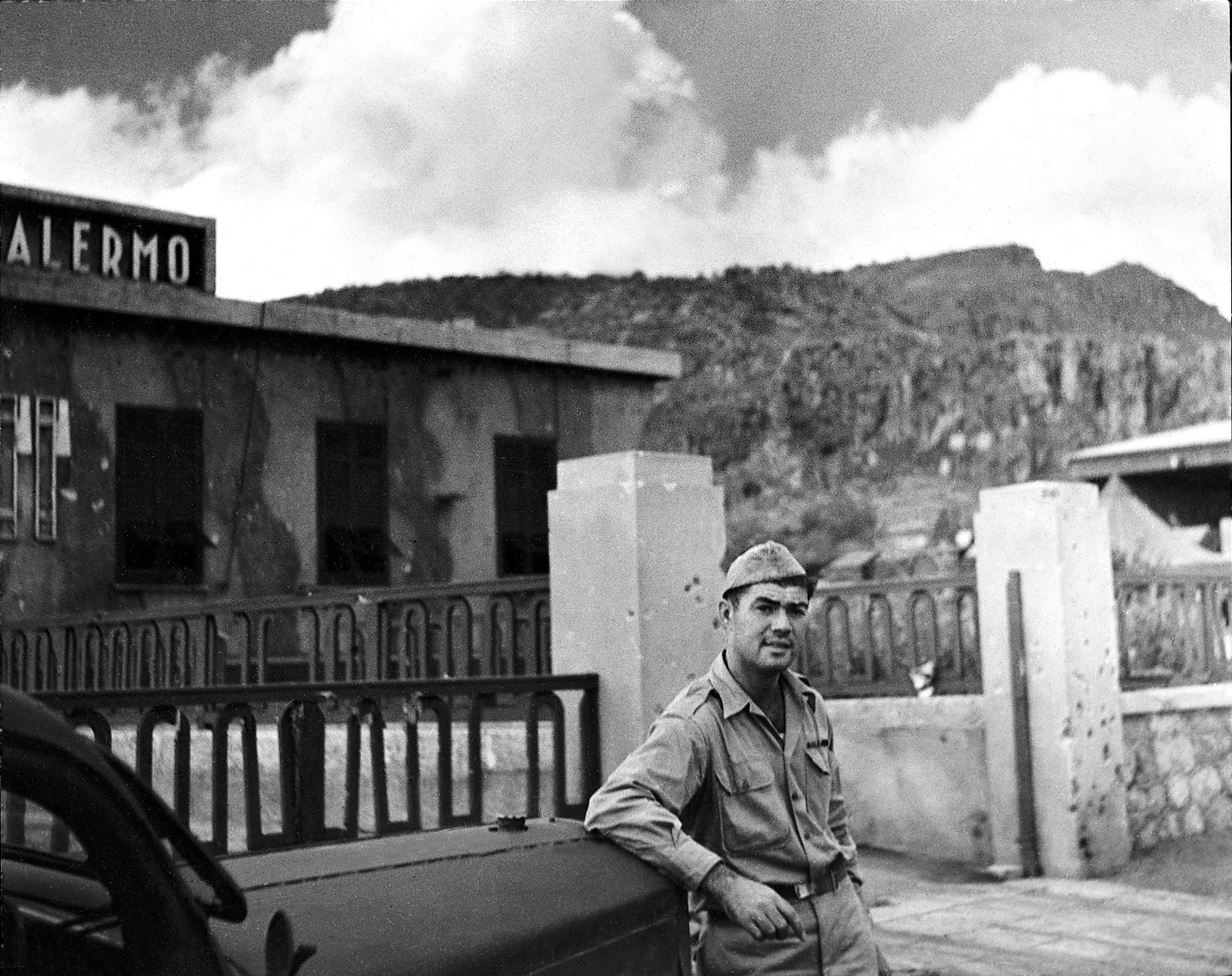

Many people ask me what some of my favorite Phil Stern photos are. It’s tough to answer, as he made so many great shots. One of my favorites is the headless statue of the Italian politician Ruggero Settimo in front of the Politeama Theater, built in 1874 in Palermo. The composition and clarity is striking. Quite a difference from the muddy training photographs in Scotland. I believe Phil really blossomed in Sicily. Whether it was the Italian sunlight or trial by fire in North Africa, his images from the invasion of Sicily are some of his finest work. He snapped around 300 photos in the first five days of the Sicilian Campaign.

A headless marble statue of the Sicilian patriot Ruggero Settimo stands on a 12-foot-high, multi-tiered marble monument in the Piazza Politeama square in Palermo. Heavy bombing by the Allies during the invasion of Sicily on July 10, 1943, blasted the head off the beloved politician, diplomat, and activist from Sicily who fought alongside the British fleet in the Mediterranean Sea against the French under Napoleon Bonaparte. In the background is the Politeama Theatre and triumphal arch topped by a bronze quadriga depicting the “Triumph of Apollo and Euterpe.” Phil Stern

A headless marble statue of the Sicilian patriot Ruggero Settimo stands on a 12-foot-high, multi-tiered marble monument in the Piazza Politeama square in Palermo. Heavy bombing by the Allies during the invasion of Sicily on July 10, 1943, blasted the head off the beloved politician, diplomat, and activist from Sicily who fought alongside the British fleet in the Mediterranean Sea against the French under Napoleon Bonaparte. In the background is the Politeama Theatre and triumphal arch topped by a bronze quadriga depicting the “Triumph of Apollo and Euterpe.” Phil Stern

Although Phil was one of the first photographers to land in Sicily at Licata Beach, fellow snapper Robert Capa was also there, parachuting into Sicily with the 82nd Airborne Division. Capa missed out on the early action, as he was stranded in a tree for hours near the town of Troina when his parachute caught on a branch. After the war, the two would often run into each other. Capa would try to recruit Phil to join his new artist agency, Magnum Photos. “I said no every time because I didn’t want to get killed and it seemed like many of his photographers were dying in battle.”

The closest Phil ever got to war again was on movie sets. He lived to be 95 years old.

Phil Stern Quotes

“I didn’t want my mother to worry about me so when I told her I was a Ranger she thought I was fighting forest fires. When I was wounded in El Guettar she thought I’d fallen out of a tree.”

“You’ll never have a greater outfit than the Rangers. What fighters and what buddies. I’m proud to say I was one of them and I’m proud to say I was there.”

Snapdragon by Liesl Bradner is now available to order. Click here to get your copy!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment