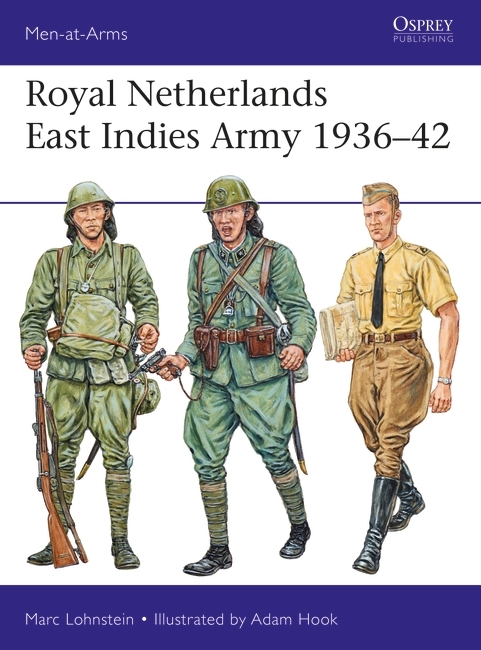

Last month saw the publication of Marc Lohnstein's new Men-at-Arms title, Royal Netherlands East Indies Army 1936–42, which looks at the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army before and during World War II. Marc joins us on the blog today to discuss Men-at-Arms 521, providing an insight into the conflict facing the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army throughout this period.

During the first phase of the war in the Pacific, the so-called Japanese southern offensive, the Netherlands-Indies and its army, the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL), played an important part. The Dutch colony – present day Indonesia – was rich in natural resources, specifically oil, and was therefore the main target of the Japanese. Furthermore, the KNIL and Dutch Navy contributed a large number of troops to ABDACOM (American-British-Dutch-Australian Command), the allied command in charge of defending Southeast Asia against the Japanese encroachment.

It was around 1914 that the last areas of the Indonesian archipelago had come under formal Dutch colonial rule. This marked the end of the so-called pacification period. The formation, organisation and armament of the KNIL were tailored to maintaining internal order and tranquillity in the vast and outstretched colony. The size of the army was relatively small, based on the limited number of troops needed to control the Dutch outer islands, the islands outside Java and Madura. The army stationed at Java served only as a back up to these troops. Java personnel rotated with those stationed on the outer islands and, if necessary, the Java troops could be deployed as an expeditionary force. The number of troops available for these tasks was only just sufficient. The organisation and armament of the KNIL was matched to those limited tasks: light infantry with support from light artillery.

The KNIL was a professional army that consisted of Europeans who signed up for years and Indonesian volunteers. It was not a reflection of the diverse ethnic groups that inhabited the colony. On the contrary, the officers and higher ranked non-commissioned officers were almost exclusively European (read: Dutch). Europeans and Christian minorities from the outer islands of the archipelago were strongly overrepresented among the rank and file. In 1929, the KNIL consisted of 38,600 troops while the total population of the Netherlands Indies was 60 million. For political and financial reasons, the potential of possible recruits was scarcely used.

By 1941/1942 the KNIL had changed into a volunteer-conscript force with more modern equipment aimed at defending Java in particular from a foreign enemy. This significant metamorphosis mainly came about between 1936 and 1942. However, the army displayed some structural weaknesses when it came to management and the buildup of personnel. An Australian officer observed in November 1941 that ‘the infantry and artillery are generally well equipped, but (…) equipment is considerably ahead of training.’ Moreover, the command at the battalion and regimental level was poor.

The political-strategic policy of the Netherlands was based on neutrality. The Netherlands did not have the means, both in terms of money as well as troops, to defend the Netherlands-Indies against a major foreign power. The principles of defence as formulated in 1927 were based on maintaining neutrality on Java and the oil-rich Tarakan and Balikpapan. The KNIL did not believe in short and limited breaches of the Netherlands-Indies neutrality, but figured that a possible attack would be a targeted all-out invasion. Its resources were therefore directed towards defending the aforementioned positions. This became the new de facto doctrine of the KNIL after 1936.

Indigenous KNIL troops, 1938

Indigenous KNIL troops, 1938

Source: Collectie Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen

For this new defensive task, the troops on Java were reorganised into the Java army. The old battalion structure was now superseded by new layers of organisation. First battalions were organised into brigades and later, from 1922 on, divisions with regiments were created, with some units that operated independently from this top down structure. The firepower of both infantry and artillery was enlarged with machine guns and some other new pieces of artillery. However, this build-up was delayed by successive severe budget cuts in 1922/1923, 1927 and 1930 and the years after that. These cuts were mainly realised by cutting down on personnel. It was only in the mid-1930s, because of the increasing international tensions in Europe and Asia, that these cutbacks were halted. From 1936 on, the defence budgets started to increase again.

The guideline for the build-up was the reinforcement plan of 1936. This plan sought to enhance the military capacities of the army. But the KNIL did not seek to achieve this increase in fighting power through a large expansion of the number of troops, but through improvements in its military equipment. This was laid down in an eight-point programme, which was expected to take four or five years to complete and which would have to commence in 1938 or 1939. The main points of the reinforcement plan called for additional bomber planes for the air force, the establishment of tank units and the purchase of medium machine guns and mortars for the infantry and finally it aimed to fill the gaps in personnel.

Modern anti-tank and anti-aircraft artillery was purchased to combat possible attacks from aircraft and armoured vehicles. The amount of new equipment that actually reached the Indies was modest though, since the orders were put out during a time when the arms market was already overheated with demands from all sides. To complicate matters, the traditional European arms suppliers were cut off after war broke out in Europe in 1939/1940 and American war production still had yet to get into full gear. An exception to the difficulties getting arms were the mortars. By the end of 1941, the KNIL owned 30 pieces of modern anti-tank artillery, 70 anti-tank rifles, 102 pieces of modern anti-aircraft artillery and 276 81mm mortars. Regarding combat vehicles, the KNIL counted 24 tanks and 142 armoured vehicles among its possessions. More modern material had been ordered, but could not be shipped in time.

The modernisation of the air force was the main priority of the KNIL. This came at the expense of the army. The KNIL adopted the strategy of indirect defence through the use of horizontal bomber planes. These bomber planes could attack enemy fleet units before their troops could disembark. Originally, this strategy was only envisioned for Java. Later, this aerial strategy was broadened to encompass much more territory, all the way to the edges of the outer islands. The bombing fleet was supplemented in 1940 and 1941 with single-seat fighter aircraft that could be deployed for escorting the bombers, supporting local air defence of several ground objects and delivering air support to troops on the ground. All in all, this lead to a rapid growth, both in material as well as in personnel, for the air force between 1936 and 1942. Yet the planned war organisation targets were not all met. Apart from the enlargement of the air force, the replacement of the bomber fleet was scheduled for the beginning of 1942, but this ultimately came too late.

To support the adopted strategy of indirect defence, airfields were constructed all throughout the archipelago in the shape of three lines of air defence. The first line was along the outer border of the Indonesian archipelago. The second line was along the north side of the Java Sea. And the last line went from South Sumatra, across Java, to Bali.

Aside from the core of European volunteers who had signed up to serve for several years on end, the KNIL instated the draft for Europeans in 1917. Starting in 1938, all kinds of short term drafts were added to this. A limited draft for Indonesians was introduced in July 1941. The first two annual contingents of conscripts reported for duty on 27 October and 1 November 1941. These 6,000 men were only just beginning their military training when Japan attacked. They would never see action. As a result, it meant that after mobilisation the KNIL was 114,000 men strong in December 1941. 94,000 of these were deployed on Java.

In 1941, on the eve of the Japanese southern offensive and inspired by the German use of mechanised warfare in Western Europe, it was decided the KNIL was to be drastically reorganised and expanded. This plan sought to motorise and mechanise its infantry. To this effect, five mixed brigades and one mobile brigade were to be formed under the direction of three division staffs. But on the eve of the Japanese landings on Indonesian soil these plans had not yet fully come into being. It meant that the mobile troops consisted of four infantry regiments with support troops. Only seven out of the 16 infantry battalions had been motorised. However, the cavalry had become almost fully motorised. The Japanese invasion hit the KNIL in the middle of an extensive reorganisation.

Through a well-organised joint operation, Japanese land, sea and air forces soon broke through the resistance lines of the KNIL. The isolated garrisons in the outer islands were eliminated one by one. The Royal Netherlands Navy sought and found a naval confrontation together with its allies. But the Imperial Japanese Navy emerged as superior from the Battle of the Java Sea. At the end of February and the start of March, the Japanese 16th Army performed amphibious landings on three different locations on the east and west side of Java. It put almost 55,000 troops on shore. The KNIL and its allies had the upper hand in sheer numbers though: 94,000 KNIL forces, 3,500 British troops, 2,500 Australians (excluding RAF and RAAF forces) and 900 Americans. And both parties seemed to be equally equipped with material. The Japanese infantry had more direct fire power with its grenade launchers and infantry pieces. The Japanese had the clear advantage when it came to the number of aircraft and tanks. Ultimately the quick and aggressive Japanese forces outwitted the mostly static allied defences both operationally and tactically by making full use of their airpower. The use of their air power proved to be of decisive importance throughout the whole campaign. On 9 March, the KNIL surrendered.

To read more about the KNIL, get your copy of Royal Netherlands East Indies Army 1936-42 by clicking here!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment