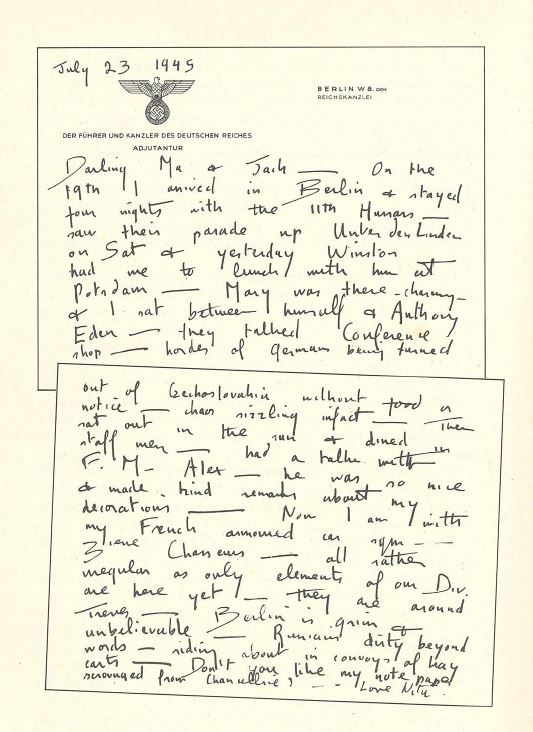

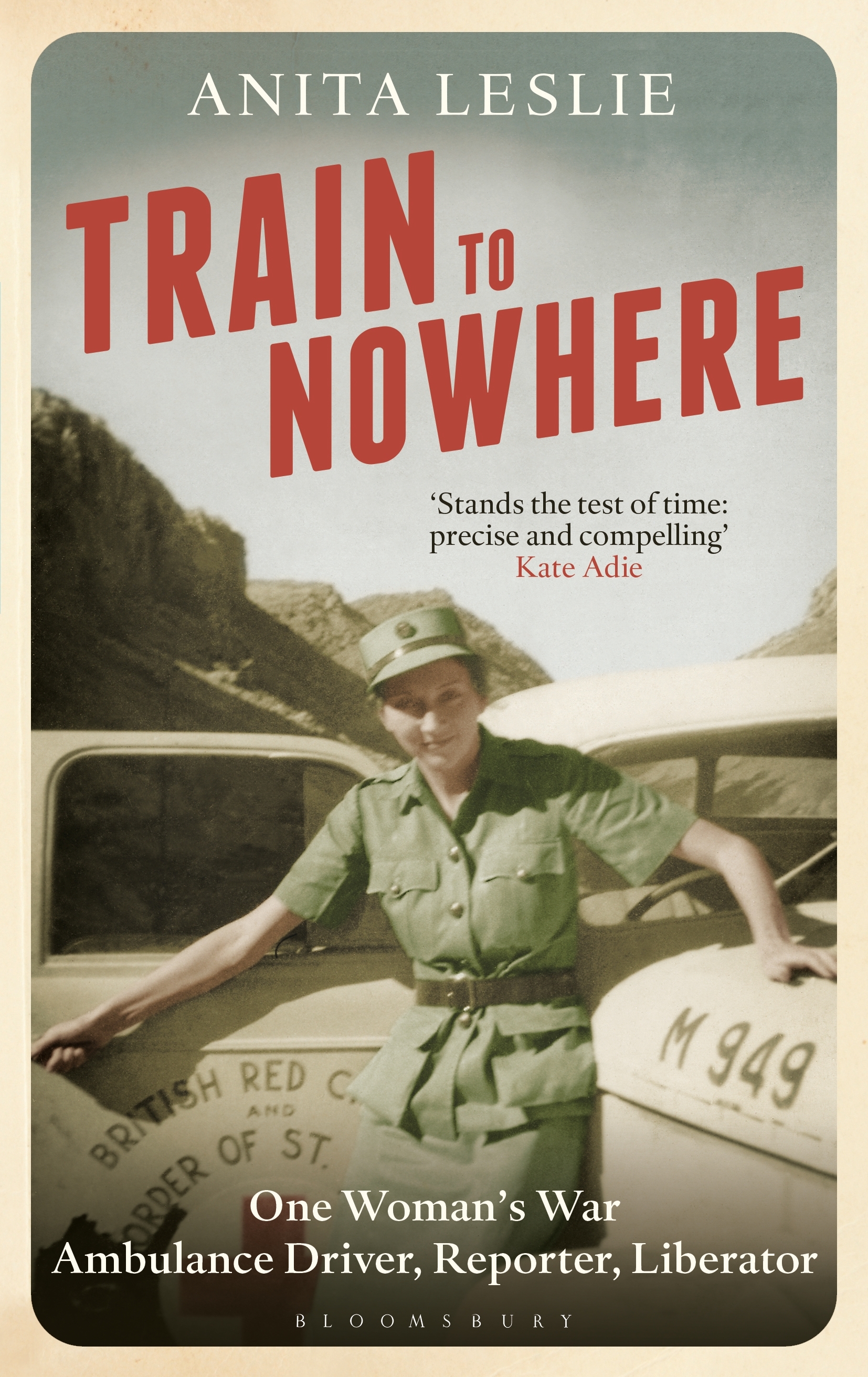

Today marks the release of the captivating memoir of Anita Leslie, Train to Nowhere. Leslie, daughter of a Baronet and cousin of Sir Winston Churchill, became a female ambulance driver during World War II, first for the MTC and then the Free French Forces, serving in Libya, Syria, Palestine, Italy, France and Germany. Below is the introduction to the fascinating memoir, published by Bloomsbury.

Anita Leslie was not the sort of person usually found on a battlefield. During the first winter of the Second World War, when both her brothers and most of her friends were active in the fight against Hitler, Anita was cubbing in Northamptonshire. She wrote to her friend Rose Burgh: ‘I feel I am “helping the war effort” by having as pleasant a time as possible which is just what he [Hitler] doesn’t want.’ Later, from London, she wrote to her mother, Marjorie, in Ireland: ‘You can’t imagine how bored people are with the war here. No one wants to listen to fancy speeches.’ The fancy speeches were made by Anita’s cousin, Winston Churchill, and inspired a nation.

What persuaded Anita to volunteer for active service was a need to escape from an exhaustingly tangled personal life, circumstances not referred to in her searing war memoir, Train to Nowhere. She enlisted as a driver in the mechanized transport corps (MTC), a voluntary organization much favoured by upper class young women such as Anita, who could afford to pay for their own chic uniform designed by the couturier Hardy Amies. As she sailed to Pretoria on the Arundel Castle through U-boat infested waters, she revelled in the novelty of freedom, writing to Rose: ‘Never again am I going to live a dull domesticated existence – I’m just going to be naughtier and naughtier! He he. ’ She may sound shallow but she came from a class that required its young girls to be light-headed and giddy. ‘Smile dear, it costs nothing,’ Anita’s grandmother, Lady Leonie Leslie, often admonished her. Marjorie’s advice to her daughter, about to head off to the Desert War, was ‘Don t get sunburned in Africa – men hate it. ’

In Cairo, the MTC tended the wounded in intense heat, hot winds and ‘maddening discomfort’ before being incorporated into the auxiliary territorial service (ATS) when the unit reached Alexandria. Anita, sensing correctly that it would be stuck in Egypt when the war moved elsewhere, manoeuvred herself into more adventurous roles – editing a newspaper, the Eastern Times, joining the Transjordan Frontier Force, where she delivered supplies to isolated field hospitals in Lebanon and Syria with her friend Pamela Wavell, who made these hazardous trips wearing a white dress and picture hat.

Anita and soldiers posing with a tank

Anita and soldiers posing with a tank

They did things differently in France. Train to Nowhere is dedicated to Anita’s commanding offi cer, Jeanne de l’Espée. Her first command to the new recruit was ‘Whatever happens, remember to use lipstick because it cheers the wounded. ’ In England, the iconic blonde bombshell recruiting poster designed by Abram Games for the ATS was rejected as being too glamorous. Amid the sound of gunfire, kitted out in American soldiers ’ outfits, including ‘comic underwear ’ – a far cry from Hardy Amies couture – eating tinned beans off tin plates, Anita was a front-line ambulance driver in the 1st French Armoured Division and played a vital part in the liberation of France. Driving in the pitch-dark through woods full of Germans, Anita wrote to Marjorie that she had never enjoyed life more. The fighting went on for months as the allies drove north-eastwards towards the Rhine, with heavy casualties on both sides. How sharply, and horrifyingly, Anita describes the battlefields: ‘In all directions, men advancing through the fi elds were suddenly blown up in a fountain of scarlet snow.’

Train to Nowhere, subtitled ‘An ambulance driver’s adventures on four fronts’ was first published in August 1948 and was widely considered to be the best book about the war to have been written by a woman – a dubious compliment. Reviewers recognized Anita’s ‘impersonal integrity’ and her unique point of view, ‘a terse, keen reticence and the summing up of deadly situations in a line or two’ TheTimes. The book sold out quickly, was reprinted twice and then forgotten. In the early post-war years, women were under pressure to revert to their pre-war role of angel in the house. Nobody wanted to hear about their exploits in bombed out villages or rescuing the dying in fields of blood. Anita herself didn’t write or talk about the war until 1983 when she wrote a lighter version of her wartime life. By that time, she had become well known for her gossipy biographies of her Churchill and Leslie relations. How gratifying that Train to Nowhere, the most heartfelt and absorbing of her books, is being revived for a new readership.

Penny Perrick 2017

Click here to read more and purchase your copy of Train to Nowhere, now available.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment