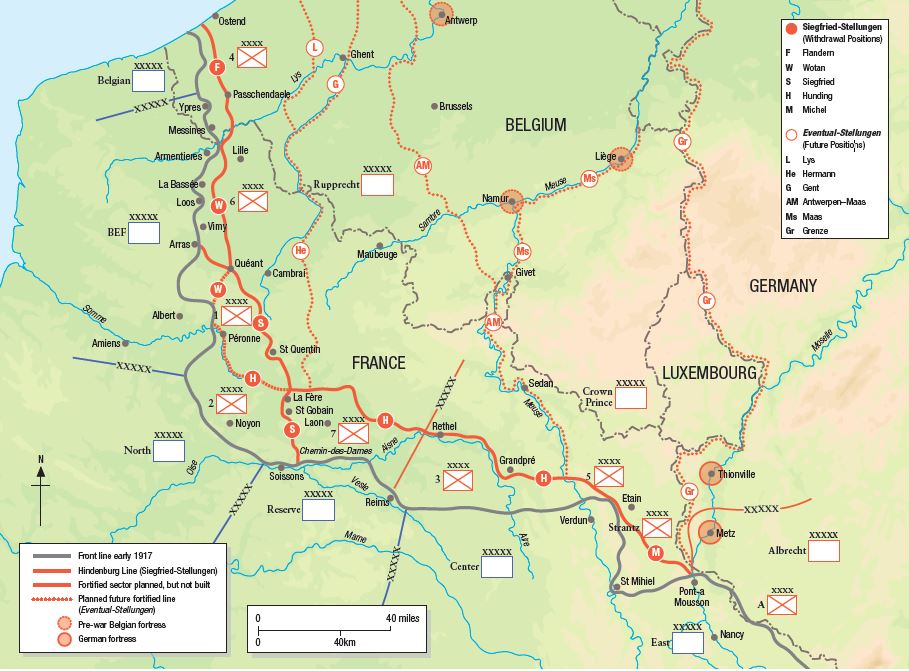

Today marks the 100th anniversary of the German withdrawal behind the Hindenburg Line. On the 16th March 1917, German troops began their withdrawal as part of Operation Alberich, which saw a retirement of 40 kilometres. The Allies would eventually break through the line at the end of the Hundred Days Offensive (8 August – 11 November 1918), signalling the end of the war, as well as the German Empire.

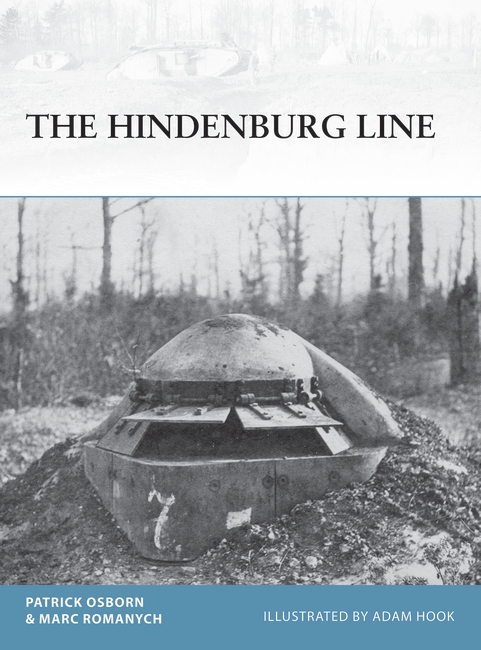

Below is an extract from Fortress 111: The Hindenburg Line by Patrick Osborn and Marc Romanych, which traces the genesis of the Line to its operational history. This extract features 5 ways in which the German Army organised the Line’s defensive position in addition to the use of trenches.

1. Wire Entanglements

Broad belts of barbed-wire entanglements were emplaced forward of the fortified positions to slow an Allied attack. The trace of the entanglements followed an irregular path, zigzagging in front of the trenches to provide fields of fire for machine guns. Additional entanglements were placed throughout the battle zone between trench systems, along communication trenches and around strongpoints to limit the advance of any infantry that penetrated the forward defences. The intervals between the belts were sometimes filled with wire set at ankle height to trip attacking infantry or pointed iron stakes to injure them.

2. Concrete shelters

The German Army built many more concrete fortifications than the Allied armies. The use of concrete began in mid-1915 when earth and timber shelters were strengthened with concrete roofs supported by joists of iron rails. However, these shelters could not stand up to artillery fire and were replaced in 1916 by shelters made of either poured concrete or pre-cast concrete block reinforced with iron rods. However, while these structures were significantly stronger, they could still be destroyed by a direct hit from heavy artillery and did not adequately protect occupants from the concussive effects of a near miss. Thus, for the Siegfried positions, even stronger shelters made of concrete reinforced with iron rods were built to replace the older poured concrete and block structures, although concrete block construction continued in forward areas where building with reinforced concrete was impractical because of the proximity to Allied lines. The primary purpose of these shelters was to protect soldiers from Allied artillery bombardment. However, other shelters were designed and built to also function as machine gun emplacements, observation posts, command posts, communication centres and medical aid stations.

3. Artillery positions

During the artillery battles of 1916 at Verdun and the Somme, the German Army stopped building shelters for artillery pieces after finding that guns placed in them were easily detected and destroyed by Allied artillery. As an alternative, the artillery turned to mobility and concealment for survivability. Thus, in contrast to the elaborate concrete shellproof shelters built for infantry units, artillery and trench mortar batteries were emplaced in open earthworks. Field-gun emplacements were dug so that the guns had a wide field of fire while trench mortars were emplaced in simple pits. Sometimes shallow dugouts with splinter-proof cover or cut-and-cover shelters were provided for the crews and munitions. Multiple emplacements were prepared so that the guns and mortars could frequently move to alternative positions. Larger-calibre indirect-fire artillery was located well to the rear, behind the second trench system, yet close enough to the front lines so that the guns could concentrate fire on an Allied attack. Emplacements for the guns were little more than a level spot on the ground. Within a battery position, trenches and timber-frame shelters covered with corrugated iron and earth were sometimes built to protect the crews and munitions. Anti-aircraft guns were also emplaced in simple earthworks, although concrete shelters were built to house searchlights.

4. Tank defences

The German Army began building anti-tank obstacles into the Siegfried positions in 1918. The purpose of these was to slow the advance of tanks and channel them into the fire of field guns or heavy artillery. The obstacles were arrayed in multiple lines of defence along likely approaches such as broad fields, valley bottoms and roads. Gaps were left in the obstacle lines to allow movement of their own troops through the battle zone. To the Allies, the presence of anti-tank defences indicated the Germans had assumed a defensive posture and had little intention of going over to the offensive in that sector. With no set design, anti-tank obstacles were improvised constructions made by troops using locally available materials. The three basic types were ditches, barricades and minefields. Anti-tank ditches were dug forward of the fighting trenches and were occasionally created by deepening and widening an existing trench line.

In mid-1918, the German Army employed anti-tank mines. The mines were designed to detonate under the weight of a tank and were emplaced in lines up to 2–3 miles (about 3–5km) in length. A single minefield could contain 7,000 mines. Minefields were generally placed forward of the first belt of wire entanglements in the outpost zone. To add depth to anti-tank defences, additional minefields were also emplaced further back in the battle zone in combination with other obstacles.

5. Camouflage

Great lengths were taken by the German Army to mitigate Allied ground and aerial observation of the fortified positions. Although most trenches and entanglement belts could not be hidden from aerial observation, simple measures such as cut vegetation or brush screens were used to conceal trenches and entanglements from ground-level observation. Therefore, camouflage and concealment focused primarily on shelters, dugouts and artillery positions. Shelters were concealed within the trench lines by building them at ground level and covering them with earth so that they looked like part of the trench wall. The facades of the shelters were camouflaged with vegetation and the concrete was sometimes stippled to blend it into the natural surroundings. Above ground, shelters and emplacements were particularly difficult to hide. These works were camouflaged with piles of earth or brush laid against, or on, the shelter to break up its silhouette. Shelters were also built into existing buildings or made to look like a building. Artillery emplacements and other open earthworks were camouflaged with canvas netting or cut vegetation. Decoy trenches, earthworks and artillery positions with dummy guns were built to draw artillery fire away from real positions.

To read more about the Hindenburg Line, see Fortress 111, which features detailed maps and historical photographs, as well as documenting the history of Germany’s most formidable line of defence during World War I. Click the link here to purchase a copy.

© Osprey Publishing

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment