Today marks the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Cambrai. Fought during World War I, the First Battle of Cambrai saw the birth of armour being used as an operational shock tactic. Following years of tiny gains for the Allies, which were always at the price of huge casualies, the first day at Cambrai saw incredible gains, advacing further in six hours than in three months at Passchendaele. However, the German counterattack that followed was incredibly costly for the Allies, and by the end of the battle on 7 December 1917, both sides had suffered heavy casualties.

Below is an extract from Campaign 187: Cambrai 1917 by Alexander Turner, describing the moment warfare changed on the Western Front, as the British put into action their plan.

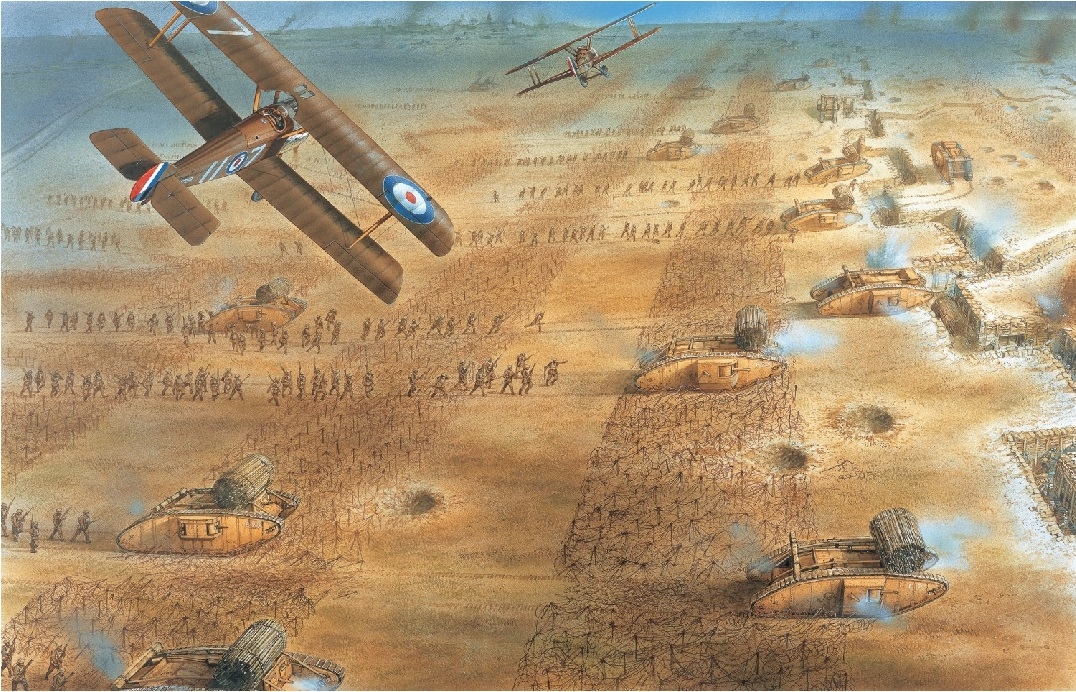

'The tanks lurched forwards at 0610hrs precisely – ten minutes ahead of Z-Hour. Their form-up locations were half a mile or so behind the front line to minimize risk of them being heard getting into position. It also gave them a rolling start to achieve section formation.

In the blue-grey twilight, the folds of rolling countryside were blanketed in a cold pale mist; distant woods still just thin bands of black ink on the scene. In the communications trenches and sunken lanes parallel with the leisurely advance, stiff infantrymen were helping each other up, shrugging into a more comfortable fit on webbing equipment while their officers squinted to identify the allotted tank section.

The advance of III Corps on 20 November 1917

The advance of III Corps on 20 November 1917

Inaudible to the tank crews but heartening to any infantryman was the unmistakable, croaky whistle of passing shells. Z-Hour – 0620hrs. German front-line positions became delineated with a brilliant band of rending explosions, blast waves pulsing palpably in the damp morning air. German sentries were launching distress flares, a signal for their artillery to respond. Nothing came over in reply. British counter-battery missions were being fired from the heavier guns further back, suppressing or destroying their counterparts with remarkable precision. The regime of silent registration was vindicated, particularly as many of the Germans in front-line positions were content to remain sheltering in dugouts. They expected the bombardment to continue for some time before any assault.

The first thing to greet Advance Guard tanks was the wire. Even though the tanks had proved their wire-crushing credentials before, commanders still felt trepidation as the great swathes came into view. These belts were dense, but not impenetrable. Tanks had no difficulty forging through. In their wake, they left springy, matted beds for the infantry to negotiate, like walking on giant-sized scouring pads.

In most places, the outpost line was vanquished almost without breaking stride. Dazed defenders felt the weight of this irresistible onslaught and threw their hands up. Nevertheless, the state of terror and panic caused by the tanks is probably overemphasized. By now, many German infantrymen had seen them before. What they were not prepared for was the shock effect of an attack mounted with such surprise and momentum. Even if they did put up resistance, the tide enveloped them hopelessly quickly.

Throughout their depth, the Germans were also being subjected to ground attack by III Brigade RFC. Flying so low that one pilot recalls having to literally ‘leap over’ tanks, ground fire was a significant hazard, accounting for casualty rates of approximately 30 per cent per day. Even so, their contribution was telling. As planned, rear areas were harassed, artillery batteries bombed, troops and horse-drawn vehicles strafed. Pilots flew sorties all day, landing to refuel, re-arm and charge their courage with a slug of strong brandy.'

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment