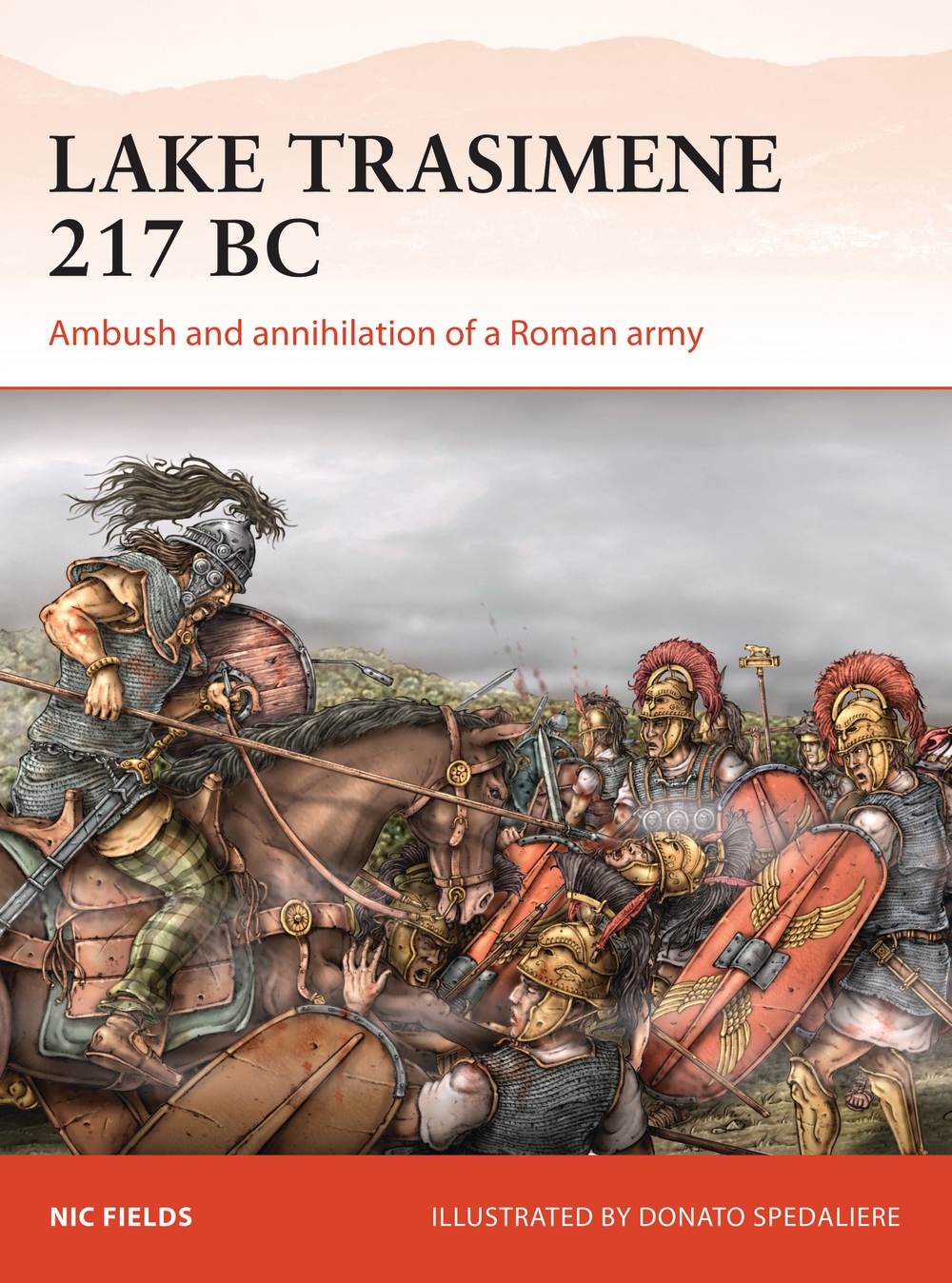

In advance of the publication of his latest book Lake Trasimene 217 BC, Osprey author Nic Fields discusses a less studied aspect of the legendary Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca: his sense of humour.

Chances are, if you are reading this, you are a fan of Hannibal Barca. If that is so, it is probably true too that when you think of Hannibal you are likely to do so with a certain degree of endearment, seeing him as the luckless but bewitching Carthaginian general who marched over the Alps, elephants and all, to take on the might of eternal Rome on its home turf. Yet, in spite of Hannibal’s amazing quartet of victories over the Romans at Ticinus, the Trebbia, Lake Trasimene and Cannae, Rome was not brought to its knees.

On the contrary, it endured through a bitter war of ugly attrition, and ultimately it was Hannibal who lost. It was that second Hannibal (but without the elephant), Napoléon, who allegedly stated, “Victory belongs to the most persevering”. Victory over Rome undoubtedly evaded Hannibal, but his perseverance never left him. But this particular Hannibalic trait is not the subject of this short article; on the contrary, it is his humour. Nowadays, what we often overlook is the fact that Hannibal was a wit and regarded jokes as an essential ingredient of man management. The ones we know about take the form of satiric anecdotes, blunt and boisterous in tone.

It is clear that Hannibal could be a cheerful card, particularly when the chips were down. When viewing the Roman behemoth preparing for the approaching struggle on the dusty, windswept plain of Cannae, one of his senior officers, a certain Gisgo, commented nervously on the number of the enemy. Hannibal turned to him with a grave look on his face and replied: “Yes Gisgo, you are absolutely right, but there is one thing you have not noticed, which is even more amazing”. “What is that, sir?” asked the puzzled Gisgo. “In all that great number of men opposite us there is not a single one named Gisgo”.

This is exactly the sort of humour soldiers appreciate. At this point, we must imagine, the entire Carthaginian staff broke into gales of laughter, and their hilarity rippled through the ranks of the waiting Carthaginian army. For Hannibal there were no hopeless situations (naturally), only hopeless men. The Carthaginian David then squared up to the Roman Goliath. The slow descent into one of the most tragic episodes in the annals of Roman military history had begun… with a piece of virtuoso foolery.

(image from CAM 303: Lake Trasimene)

(image from CAM 303: Lake Trasimene)

It is also clear that Hannibal could play the role of licensed court fool (as opposed to bootlicking court sycophant). As the armies were deploying to commit themselves to the lottery of battle, it is reputed that Antiochos of Syria turned to Hannibal, who was accompanying the Seleukid king as part of his bloated entourage, to enquire whether his army, its serried ranks shimmering with silver and gold, its commanders grandly arrayed in their heavy precious jewels and rich oriental silks, would be enough for the Romans. “Indeed they will be more than enough”, sneered Hannibal, “even though the Romans are the greediest nation on earth”.

Antiochos was one of the greatest Hellenistic monarchs who – in conscious imitation of Alexander – bore the epithet ‘the Great’, a title he had earned attempting to reconstitute the Seleukid kingdom by bringing back into the fold the former outlying possessions. He thus managed to reassert the power of the Seleukid dynasty briefly in the upper satrapies and Anatolia (Roman = Asia Minor), which effectively made him ruler of the eastern world from the Indus to the Aegean. One gains the distinct impression that Hannibal was none too impressed with all this eastern promise.

There is a Latin proverb that runs like this, Aut viam inveniam aut faciem, “We will either find a way, or make one”. This particular proverb (it was commonly said) was attributed to Hannibal in response to his senior officers who had voiced their collective doubts about crossing the precipitous Alpine paths with elephants. It does not require brilliant insight to understand their worried concerns on this matter – after all, the Alps were not a paper obstacle – but, and here is the snag, Hannibal would have spoken Punic not Latin.

This brings us to Punic names. The Carthaginian nobility used only a handful of forenames, which makes reading their history confusing at times. A case in point. One of Hannibal’s senior officers was also called Hannibal, nicknamed Monomachos (‘the Duellist’), who could have also appropriately been nicknamed ‘the Cannibal’. In one council of war on the eve of the great invasion he advised that during the crossing of the Alps, the men could eat any of their comrades who perished along the way if provisions ran short. In reply Hannibal said, tongue planted firmly in cheek, that he appreciated the practical value of cannibalism but could not bring himself to consider it. Clearly this was one option Hannibal did not wish to take.

The great general, when in exile at Ephesos, was once invited to attend a lecture by one Phormio, a noted Greek philosopher, and after being treated to a lengthy discourse on the art of generalship, was asked by his friends what he thought of it: “I have seen many old drivellers”, he replied, “on more than one occasion, but I have seen no one who drivelled more than Phormio”. Warlike and brilliant, Hannibal not only had a keen eye for strategy and tactics but also scholarship.

As a boy he had received a good education, which had included a strong Greek element. On his invasion of Italy Hannibal was to take Greek historians with him, including the Spartan Sosylos, his former tutor who had taught him Greek, and the Sicilian Silenos, though in what capacity he had taught the young Hannibal we do not know.

He established himself as something of a literary lion, even to the extent of having written works in Greek, including one addressed to the Rhodians on the Anatolian campaigns of Cnaeus Manlius Vulso. His Greek training made him intellectually the superior of any of the Roman commanders (excepting Publius Cornelius Scipio, perhaps) he was to face upon the field of conflict.

It comes as no surprise to learn that among its enemies Rome’s chief bête noire was beyond question Hannibal, and the Latin proverb Hannibal ad portas would retain its efficacy as a rallying cry for Romans in times of national crisis again and again, like a will-o’-the-wisp at dusk, until the very end of their empire. It almost seems as though the Romans did not want their greatest enemy absolutely eliminated.

Trapped, aging and defiant, Hannibal took the poison, which he always carried about his person, before a Roman snatch squad could bundle him off to Rome. In his final agony he apparently cried out: “Let us free the Roman people from their long-standing anxiety, seeing that they find it tedious to wait for an old man’s death”.

True or not, whether this exit line occurred to him spontaneously or whether he had rehearsed it is not known, and never will be. But never mind, as he lies dying, we may well suspect, Hannibal does not bemoan the triumph of Fortune, but humbly acknowledges her absolute primacy. Fortune, who claims to be the arbiter of all human affairs, will get us all in the end; the hardest thing is to accept that reality.

True or not, whether this exit line occurred to him spontaneously or whether he had rehearsed it is not known, and never will be. But never mind, as he lies dying, we may well suspect, Hannibal does not bemoan the triumph of Fortune, but humbly acknowledges her absolute primacy. Fortune, who claims to be the arbiter of all human affairs, will get us all in the end; the hardest thing is to accept that reality.

It is suffice to say that Hannibal was not only a superlative warrior general who had a knack for thinking outside the box, but also a consummate wit whose sense of serenity allowed him to maintain good humour and joke around even in the midst of battle.

The limited evidence for the events of Hannibal’s complex life come not from Carthaginian sources but those of his Roman enemies. However, those of you who wish to check out these Hannibalic anecdotes the references are as follows: the conversation between Hannibal and Gisgo is given in Plutarch, Fabius Maximus 15.2-3; that between Hannibal and Antiochos in Aulus Gellius Noctes Atticae 5.5; the story of Hannibal Monomachos in Polybios 9.24.5-8; that of Phormio in Cicero de Oratore 2.75; and the details of Hannibal’s death in Livy 39.51.9 and Nepos Hannibal 12.5; on Hannibal’s education and learning see Nepos Hannibal 13.3, Cicero de Oratore 2.18.75, Vegetius Epitoma rei militaris 3 preface.

Lake Trasimene 217 BC by Nic Fields is publishing on Thursday 23 January and is available for pre-order. Click the link in the book title above to place your order.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment