On 27 July, we'll be publishing Whispers Across the Atlantick by David Smith, a fantastic and original insight into the life of the British general William Howe, who acted as the commander-in-chief of the British forces during the early campaigns of the American Revolutionary War. Today on the blog David reveals how he came to writing his second book on the enigmatic general and how without a certain draft Whispers Across the Atlantick might never have existed.

What does a historian do when the evidence runs out? This question was posed by the great military historian John W. Shy, while we were discussing my PhD research in 2011. The question was particularly relevant to my work, because there isn’t a lot of primary source material dealing with General William Howe, who commanded the British army in America during the first two years of the American War of Independence.

I’d been fascinated by Howe for more than 15 years by that point and, after a few hiccups, had managed to embark on a doctorate at the University of Chester. I believed (or at least hoped) that more could be dug up on this enigmatic commander, who left behind no substantial collection of papers for an inquisitive historian to delve into. I expected my research to find me elbow deep in correspondence stored at the National Archives at Kew, trying to glean every last bit of information from documents that had been well studied before. More promising (and no doubt more exciting, not that I have anything against the National Archives) was a planned visit to the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan. The Clements Library is affectionately referred to as ‘British HQ’ for the War of Independence. They own many substantial collections and, with the buying power of American universities, tend to scoop up any new ones that come on the market as well. The papers of General Henry Clinton, Howe’s troublesome second-in-command, were of most interest to me and even though it would not be a cheap trip, it was an essential one.

Still, the Clinton Papers weren’t exactly unknown, and had already been thoroughly researched. So what if I couldn’t find anything new? A PhD demands an element of originality, so if I couldn’t dig up a new letter I would be relying on a new interpretation of existing documents, which is always tricky, especially when thousands of books have been written on the subject of the War of Independence.

Then, in February 2010, a story in the Telegraph hinted at something new. A collection of papers was being put on sale. The papers, including letters from British officers in America during the revolution, had been held in a private collection for 200 years. There was a good chance that at least some of these had never been studied before. The papers were due to be auctioned at Sotheby’s, in New York, and it was a near certainty that an American institution would end up buying them. There was, however, the outside chance that another private collector would snap them up, and they might not be interested in letting historians look at them.

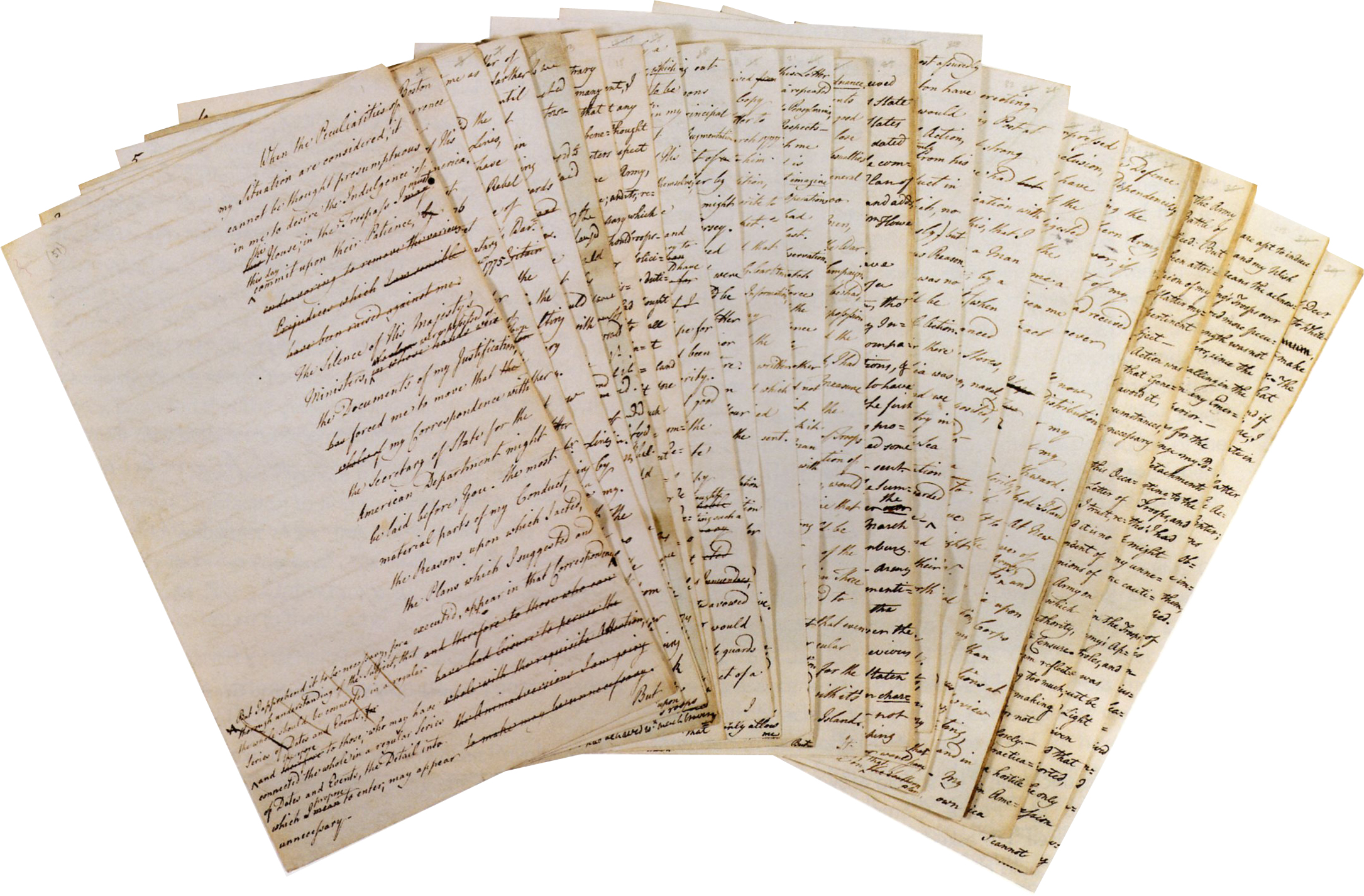

Sotheby’s produced a beautiful catalogue of the collection, known as the Henry Strachey Papers. Strachey had been secretary to the Howe brothers (William and his older brother Richard, commander of the British fleet in North American waters) in their role as peace commissioners. The catalogue was interesting, but there didn’t seem to be much that was particularly revealing—until I came to page 24. Under a picture of a pile hand-written papers was the heading: General Howe’s ‘Narrative’.

(Source: Henry Strachey Papers)

Howe’s narrative will be familiar to most students of the American Revolution. After failing to win the war, Howe had returned home under a cloud and had called for an inquiry into his personal conduct. As part of this inquiry, he had stood before the House of Commons and delivered a lengthy speech, detailing his decisions and actions while in command. It was a rather dull speech, which didn’t shed much light on anything, but the description in the Sotheby’s catalogue was intriguing, describing their copy of the narrative as a ‘complete early draft’. By comparing this draft with the final version, it might be possible to draw new conclusions about Howe’s decision-making. There was also the tantalising possibility that there might be some precious piece of new evidence in the draft, something that was ultimately left out of the speech and therefore forgotten for more than 200 years. The draft covered 85 pages, and could turn out to be the keystone of my entire thesis—if I could get my hands on it.

The auction came and went and I waited for news on who had bought the collection. Sometimes, if a private collector wins an auction, this information is never revealed, and there was the very real possibility of the draft of Howe’s narrative disappearing again before I’d had chance to see it. Thankfully, it turned out that the Clements Library had bought the collection, for $602,000. I would be able to study the documents, including the draft of the narrative, when I visited the following year.

In April 2011, I duly turned up in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and headed for the library. In the main room the narrative was laid out on display under a glass case and for a moment I was worried that it might not be available for scrutiny. The staff, however, assured me there was no problem and soon delivered it to my desk. There was an added bonus when I was informed that nobody else had yet come to study it.

What I read provided the original element that my PhD thesis needed. Howe was revealed to have been even more opposed to harsh treatment of the colonists than historians had believed, and the shaky ground he was on when trying to defend his performance in America seemed shakier still when several passages, deleted from the final speech, were considered. The narrative also proved what had been suspected for a long time—that Howe had a disastrous relationship with General Philip Leopold von Heister, who commanded the thousands of Hessian soldiers hired to beef up the British army. Von Heister had even refused an order from Howe to attack the rebels at White Plains at the end of the 1776 campaign.

The original evidence also convinced me that a published adaptation of my thesis was a possibility, and William Howe and the American War of Independence was published by Bloomsbury Academic in 2015. I had always hoped, however, to bring Howe to a wider audience. An academic title was fine, but I also wanted to write a popular history and, thankfully, Bloomsbury/Osprey also liked the idea. Whispers Across the Atlantick is the result, but if that draft of Howe’s narrative hadn’t shown up at just the right moment, it almost certainly would never have been written.

Whispers Across the Atlantick by David Smith will be released on 27 July 2017 by Osprey and is now available to preorder by clicking the title.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment