Richard Macrory is the author of Campaign 298: The First Afghan 1839-42 publishing on 25 August. In this blog he talks about his personal connection to the campaign, his research for this new book and the links between this 19th century conflict and the present day.

A British military invasion to secure regime change in a foreign country. Initial success in toppling the existing ruler but no proper planning of what to do once in occupation. Faulty intelligence that ignored the danger signals, and a failure to understand local politics. British forces sent with ill-suited equipment, compounded by economic squeezes from London. Confusion in lines of command between the political and the military, and several years later a mission that ended in humiliation and failure.

Chilcot 2016? In fact the story of the First Afghan War 1839-1842, and the subject of my new study in the Campaign Series. The modern resonances are all too uncomfortable.

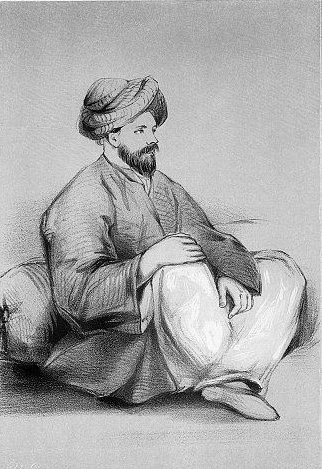

I have lived with the First Afghan War since my childhood. My great great great uncle was Eldred Pottinger (pictured left), one of a new breed of young political officers employed by the East India Company. Despite his young age he spoke the local languages fluently, and travelled extensively in Afghanistan in disguise before the British invasion. He was taken prisoner when the British finally retreated from Kabul in 1842, surviving almost nine months in captivity, and was one of the few senior British figures involved in the whole venture to emerge with his reputation intact.

When I was a teenager, my father, Patrick Macrory, wrote Signal Catastrophe (1966), the first modern account of the Afghan War, drawing on contemporary sources including Kaye’s magisterial History of the Afghan War published less than a decade after the event. There have been other studies of the First Afghan War published since then, including most recently William Dalrymple’s Return of the King (2013).

For this book, I went back to original accounts written by British participants at the time as well as more recent academic research examining British military tactics, and the complexities of Afghan politics. Focusing on the military strategies and the forces involved, it traces the First Anglo-Afghan War from the British forces crossing the Indus into Afghanistan through to the brutal rebellion and subsequent retreat from Kabul.

The campaign began with an invasion which nearly failed through poor logistical planning. It achieved its objective with small loss of life but, as many predicted at the time, the British then found they could not easily withdraw, though the politicians behind the venture remained blindly optimistic that all would eventually be well.

Three years later the core British forces were forced to retreat from Kabul. Leading to the destruction of some 4500 soldiers and 12000 camp followers, this was the first time that British forces had been so defeated by non-professional local resistance. The following year an Army of Retribution was sent to restore British pride. Its commander, General Sir George Pollock, was intent on avoiding earlier military mistakes – his meticulous logistical and military planning crushed Afghan resistance. But by then the British had lost all heart in further involvement in Afghanistan and left the country to the original ruler they had ousted four years earlier.

Artists attached to the British forces produced an extensive collection of evocative lithographs and drawings, many of which are reproduced in the book. The research also uncovered material hitherto hardly seen. I met a London art collector who had the original map used by the officer who had rescued the British prisoners. A visit to a regimental museum in Somerset unearthed in its basement a portrait of the young British officer stationed in Jalalabad who had first spotted the sole British survivor of the march from Kabul. Searching through the Kew archives uncovered a detailed map of the disposition of the forces during the siege of Ghazni produced for the commander in chief. This formed the basis for the battlefield Birds Eye View. Ghazni was considered impregnable, but the Chief Engineer attached to the forces devised a plan for secretly blowing a gate by gunpowder. One of his relatives made contact and allowed me to reproduce a family portrait of Chief Engineer Thomson. More recently I met one of the direct descendants of Lady Sale, a General’s wife who wrote a pithy contemporary diary of the whole disaster, and was later feted in London as the “Grenadier in Petticoats”.

Attack on Ghazni, 23 July 1839

Attack on Ghazni, 23 July 1839

Artwork by Peter Dennis

Kabul and the other key towns and cities in Afghanistan have grown out of all recognition since the 1840s, but the surrounding landscape and the route the British took during their retreat have hardly changed. In the early 1960s the American anthropologist Louis Dupree walked the retreat on the exact days that the British had done so many years before. He was exploring the extent to which village oral historians still recalled the First Afghan war, and found they were indeed familiar with the British names involved. His widow, Nancy Dupree, still lives and works in Kabul and we made contact. She discovered slides he had taken at the time, and a number are reproduced in the book. One of the most iconic paintings of the First Afghan War is Wollen’s Last Stand of the 44th at Gandamak, now to be seen in the Chelmsford and Essex Museum. Gandamak is far too dangerous to visit at present by any but the most intrepid but I contacted an American serviceman who managed to visit the village a few years back. His photograph of the lonely rocks where the last remnants of the British army were slaughtered appears in the book.

One would hope that modern politicians can learn from history. Yet the contemporary resonances of the First Afghan War continue to echo. The first edition of my father’s 1966 book contained a foreword by Field Marshall Sir Gerald Templer who had commanded the effective campaign against communist insurgents in Malaya in the 1950s. His words contained a veiled reference to US involvement in Vietnam - rather too sensitive for a US audience at the time, and his foreword was cut out of the American edition. General Sir Michael Rose wrote the foreword to a new edition of the book published in 2002 shortly after the commencement of Operation Enduring Freedom. He warned that “the underlying risk to the mission was much the same as experienced by all foreign powers that have sought to impose their will on Afghanistan over the centuries.” William Dalrymple found that Hamid Karzai, the new Afghan President supported by the US-led coalition, astonishingly came from the same sub-tribe as Shah Soojah, the luckless king whom the British had tried to impose on Afghanistan during the first Afghan War. Henry Kissinger once wrote, “It is not often that nations learn from the past, even rarer that they draw the correct conclusions from it.” Unfortunately his words seem all too true.

Richard Macrory's new book Campaign 298: The First Afghan War 1839-42 is available to preorder on the website now, and will be published on 25 August 2016.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment