Today marks the centenary of the Battle of Jutland, the only major fleet engagement of World War I and the biggest battleship action of all time. Osprey author Mark Lardas has delved into his research to provide an interesting look at one of the lesser known aspects of the battle.

Jutland is justly famous as the greatest surface battle in naval history. Yet it easily could have been famous for something else – being the first major naval battle in which aerial reconnaissance led to victory.

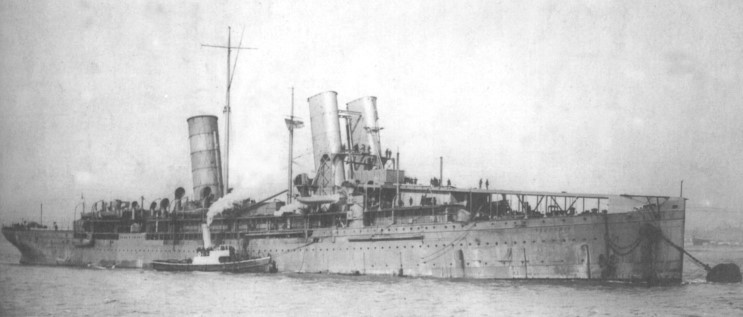

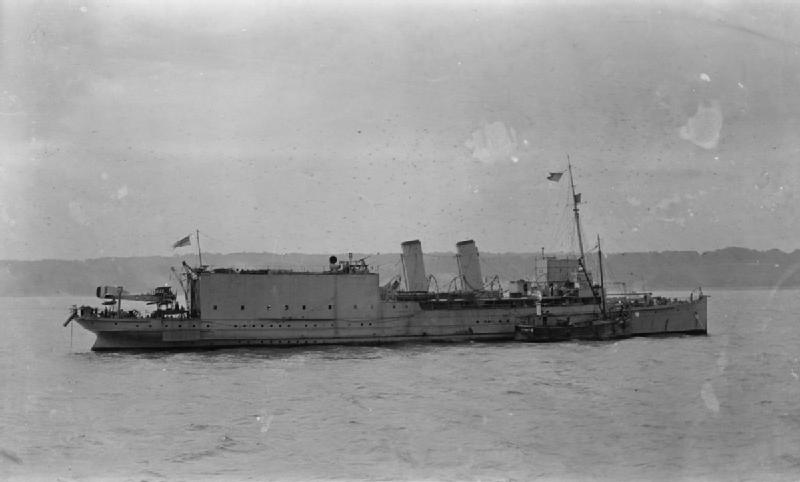

By May 1916 the Royal Navy had nine seaplane carriers in commission. Two, Campania and Engadine, were assigned to the Grand Fleet in May 1916. Campania, a former Cunard liner that had been converted to carry Short 184 seaplanes, and Sopwith Pup scouts. It was assigned to Jellicoe’s main body, stationed at Scapa Flow. Engadine, a former Channel ferry, was one of the first three seaplane conversions attempted by Britain in September 1914. At Jutland, it had two Short 184s and two Sopwith Baby floatplanes aboard. It accompanied Beatty’s Battle Cruiser Force, based at Rosyth.

HMS Campania

HMS Campania

Image courtesy of Imperial War Museum

Campania either did not get or misunderstood the signal to deploy when the Grand Fleet steamed out of Scapa Flow, and instead sailed 2 hours, 15 minutes later. The old girl (launched in 1892) cracked on the steam. It held the Blue Ribband as the fastest Atlantic liner in 1894 and 1895, and showed its old form, slowly catching up. Jellicoe, concerned about submarines and unwilling to dispatch destroyers to escort the unaccompanied Campania, ordered it back to port.

Engadine sailed with Beatty’s battle-cruisers. When two scouting light cruisers spotted a German light cruiser, Beatty sent orders to Engadine to conduct an air reconnaissance. Between 15:05 and 15:10 on May 31, a Short 184 piloted by Flight Lieutenant Frederick J. Rutland took to the air. Visibility was poor but Rutland and his observer Assistant Paymaster G. S. Trewin pushed on.

HMS Engadine

HMS Engadine

Image courtesy of Imperial War Museum

Unfortunately mist forced Rutland to fly at altitudes low enough for anti-aircraft fire to reach. The Short found itself receiving an intense and accurate barrage from three German light cruisers. At 15:30 Rutland radioed a contact report to Engadine.

Engadine received his message, but no one else did. Rutland continued signaling reports. By then German antiaircraft fire had landed seven hits. An oil line burst at 15:36. Rutland nursed his crippled aircraft home, his seaplane was recovered, and Rutland related his observations.

Engadine wrote up Rutland’s findings, broadcasting a report to Beatty. It also failed to reach its destination. By then Hipper’s battle-cruisers had opened up on Beatty’s dreadnoughts. The Battle of Jutland’s aerial reconnaissance was over. It had been completely unsuccessful.

Had Beatty received Rutland’s 15:30 broadcast the course of the battle might have changed radically. Instead of turning south to seek out the enemy Beatty might have continued east, cutting between Hipper’s scouting force and Scheer’s main body, possibly crossing Hipper’s “T”. The 5th Battle Squadron, four Queen Elizabeth-class fast battleships, would have been close at hand.

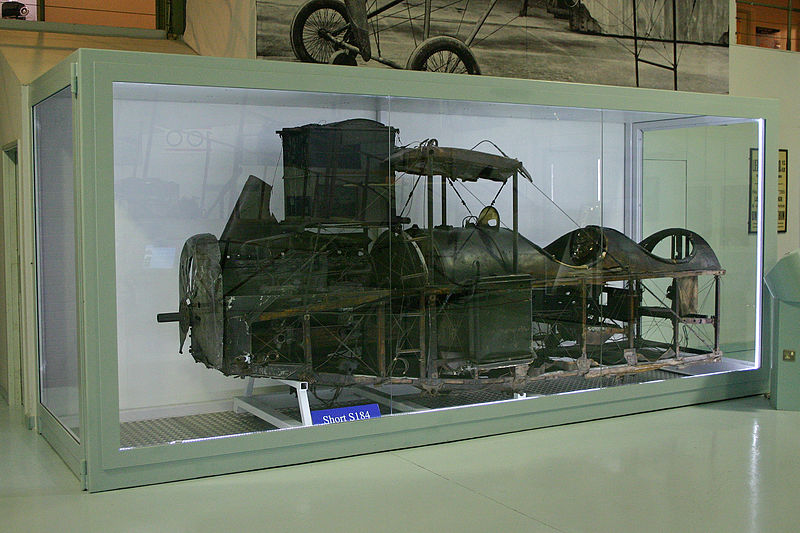

Forward fuselage of a Short 184

Forward fuselage of a Short 184

Rutland received a well-deserved DSC for his gallantry, and was thereafter known as Rutland of Jutland. He left the Royal Navy in 1922, apparently becoming a consultant. Setting up shop at Honolulu, Rutland sold his expertise on aircraft carrier operations to the Imperial Japanese Navy. British intelligence, unamused by his enterprise, interned Rutland shortly after his return to Britain in October 1941.

Campania sank after colliding with Royal Oak in the Firth of Forth on November 5, 1918. Engadine survived World War I, returning to service as a ferry. In 1933 Engadine was sold to a Philippine company, renamed Corregidor, and provided passenger service between the various islands. In December 1941, it struck a mine in Manila Bay and sank, with a heavy loss of life.

Rutland’s Short 184 went into the Fleet Air Arm museum. Damaged during a bombing raid in 1940, what is left of it is still on display at the FAA Museum in Yeovilton.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment