On 10 September 1939 the Royal Navy suffered its first submarine loss of the Second World War, with the HMS Oxley sinking with only 2 survivors. However, it was not at the hands of an enemy vessel that the submarine was lost but rather through friendly fire – the HMS Triton mistook the Oxley for an enemy submarine and fired upon it. The hearings that followed the incident showed that Lieutenant Commander H. P. de C. Steel was blameless in the incident, and that he had acted just as he should have when faced with an unidentified vessel.

Below is his testimony in relation to the tragic incident.

I surfaced at about 5 minutes to eight on the evening of 10th September and fixed the position of the ship Obrestad Light 067°, Kvassiem Light 110°. That position put me slightly west and south of my patrol billet which was No.5. My intention for the night was to patrol to the southward on a mean course of 190° and in order to get on that line I steered 170° zigzagging 30°, 15° each side of the mean course at about three to four knots, slow on one engine, charging on the other. The submarine was trimmed down. Before I went below I gave orders to the Officer of the Watch that if he saw a merchant ship he was to keep clear of her and in any case attempt to get end on. At the time there was one merchant ship coming south well away on my port quarter, and that was the only ship in sight at the time. The officer of the watch took over and I went below. Actually, we could not see this ship on the port quarter with the naked eye – only with binoculars.

Shortly before nine o’clock I was in the control room and there was a message from the bridge: Captain on the bridge immediately. I went straight up. The night was dark and there was a slight drizzle and I could see nothing except the shore lights. The Officer of the Watch informed me that there was a submarine fine on the port bow which for the moment I could not see. The ship was swinging to starboard and the officer of the watch was in charge. The signalman was sent for. In fact I am not certain whether he followed me up. I then made out through binoculars an object very fine on the port bow and I gave orders for the bow external tubes to stand by – Nos. 7 and 8 tubes

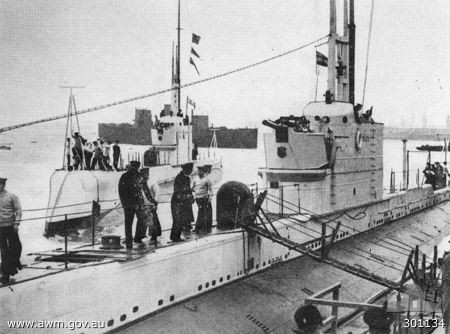

The HMS Oxley

At the same time the crew went to diving stations. I broke the charge and got on the main motors at once and it was at this moment that I recognised the object as a submarine. I took the ship and kept Triton bows on. From what I could see I appeared to be on a broad track, I should say about 120 degrees, and the object was steering in a north-westerly direction. It occurred to me that it might be Oxley and I dismissed the thought almost as soon as it crossed my mind because earlier in the day I had been in communication with Oxley and I had given her my position accurately, which was two miles south of my billet, No.5, and Oxley had acknowledged this, and I had also given him my course which was at the time 154°. By this time the signalman was on the bridge and I gave him the bearing of the object or the submarine. I told him not to make any challenge until he got direct orders from me. He knew the challenge and the reply. I then ordered the challenge to be made as soon as my sights were on and I knew the armament was ready, and the signalman made it slowly. No reply was received. After about 20 seconds I ordered the challenge to be made again. During this time I had been studying the submarine very closely indeed. She was trimmed down very low and I could see nothing of her bow or shape and the conning tower did not look like Oxley’s, and I could not see any outstanding points of identification such as periscope standards, ete.

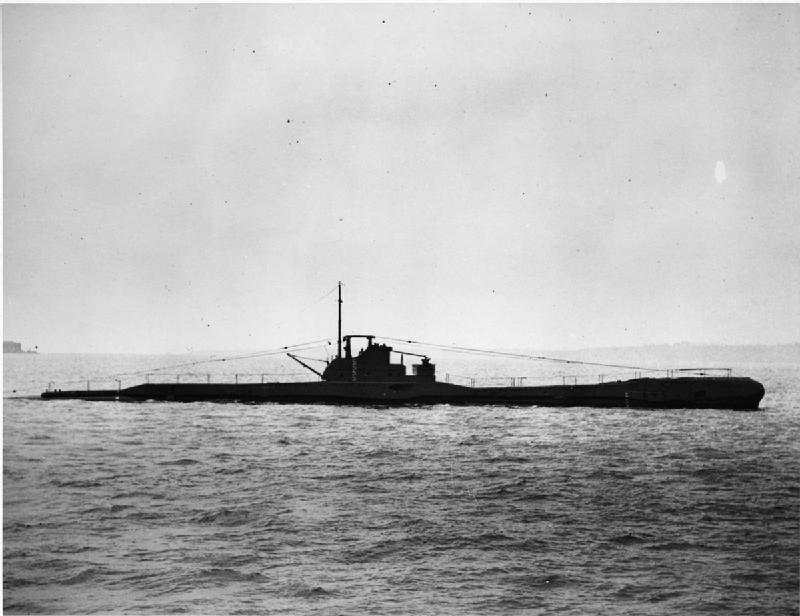

The HMS Triton

Accordingly, I ordered the second challenge to be made; received no reply to the second challenge. Receiving no reply to the second challenge, I made a third challenge again after a short interval. Receiving no reply to the third challenge I fired a grenade which burst correctly. I did not see the grenade actually burst although I knew it had burst because of the light as I had my eyes fixed on the submarine. By this time I was completely convinced that this was an enemy submarine. I counted fifteen to myself like this: and-one, and-two, andthree … When I had counted fifteen to myself! gave the order to fire; No.7 and No.8 tubes were fired at three-second intervals. About half a minute after firing, indeterminate flashing was seen from the submarine. This was unreadable and stopped in a few seconds. The Officer of the Watch also saw this. It gave me the impression that somebody was looking for something with a torch – it was certainly not Morse code. Very shortly afterwards, a matter of a few seconds after the flashing had stopped, one of my torpedoes hit. I told the Officer of the Watch, Lieutenant. H. A. Stacey, to fix the ship, and he fixed the ship as follows: Obrestad Light 035° Egero Light 105°. This fix placed the ship 6.8 miles 189° from No.5 position, which put me 4 miles inside my sector. I took the bearing of the explosion and proceeded towards the spot at once. The sea was about 3 and 2. Very soon we heard cries for help and as we came closer we actually heard the word ‘Help’. There were three men swimming. I manoeuvred the ship to the best of my ability to close the men and kept Aldis lights on. Lieutenant Stacey and Lieutenant Watkins attached lines to themselves and dived in the sea which was covered in oil and succeeded in bringing Lieutenant Commander Bowerman and Able Seaman Gukes to safety. The third man who afterwards transpired to be Lieutenant Manley, RNR, was seen swimming strongly in the light of an Aldis when he suddenly disappeared and was seen no more.

To find out more about British submarines during World War II take a look at New Vanguard 129: British Submarines 1939–45 by Innes McCartney.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment