The Cuxhaven Raid

Merry Christmas. As today is a key anniversary in the world of early naval aviation, I thought I’d mark the occasion with a Book Diaries on the subject.

Santa Claus was not the only one making aerial deliveries on Christmas Day in 1914. Exactly 101 years ago, the Royal Navy conducted an air raid against the German fleet at Cuxhaven. The British presents were the wartime equivalent of lumps of coal: bombs and bullets. The Germans could not even play with these gifts. They were expended upon delivery.

It was not a big raid. Only seven aircraft participated: three Short Type 74s, two Short Type 81s, and two Short 135s. Each aircraft carried three 20-pound bombs. But it was the first time the Royal Navy launched an air strike against a ground base using ship-borne aircraft. (Although it was not the first-ever carrier strike against land. That occurred a few months earlier in August. A Maurice Farman seaplane, based on the Japanese seaplane carrier Wakamiya bombed German and Austrian warships in Tsingtao. )

The aircraft were launched from the seaplane carriers Engadine, Empress, and Riviera. All started life as fast (for 1905–14) cross-Channel ferries. Engadine and Riviera could make 20 knots. Empress could do 18. This meant they could keep up with the battle fleet.

The three were requisitioned by the Admiralty at the war’s onset and hastily converted to carry seaplanes. In 1914 this meant adding booms to handle seaplanes and canvas hangers in which to shelter them. (The canvas shelters were replaced with metal structures in 1915.)

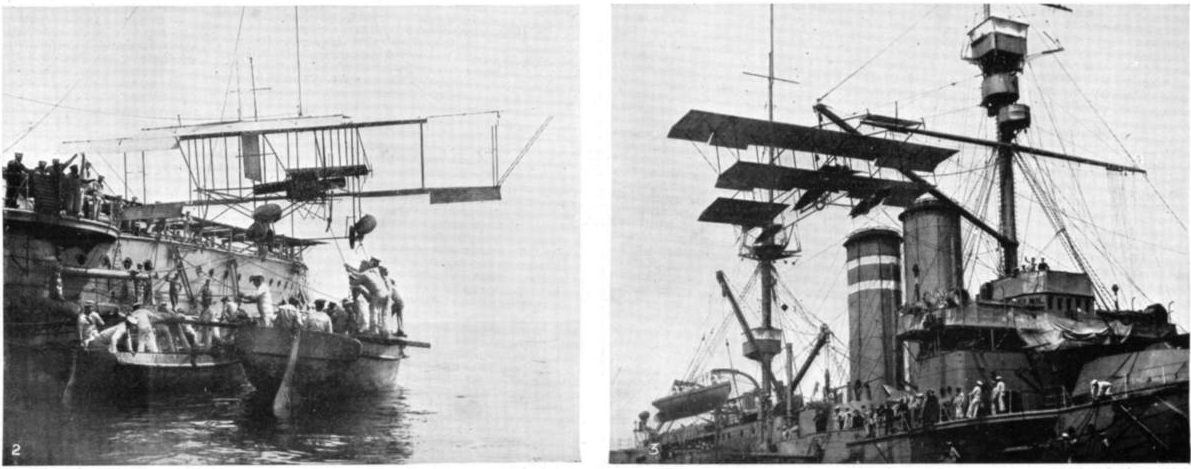

HMS Riviera in 1914 (note canvas shelter)

The raid’s primary goal was blinding Germany’s High Seas Fleet. When Tirpitz built his navy he deliberately neglected cruisers to maximize his dreadnought battleship numbers. Cruisers were almost as expensive as dreadnoughts, but not nearly as impressive. When World War I started the High Seas Fleet was caught short. The cruisers could screen the fleet or scout, but there were not enough to do both. Tirpitz turned to Zeppelins for fleet scouting.

HMS Empress in 1914 (after permanent hangar added)

The Germans did not have that many Zeppelins. In August 1914, the German Navy had exactly one Zeppelin. Even by December 1915, the navy had only 15 Zeppelins in commission. Zeppelins also required large storage sheds. The problem was reaching them. The only way aircraft could get close enough was by sea. Hence the use of Britain’s three seaplane carriers.

The aircraft were launched in fog, with predictable results. The aircraft quickly became separated. One airplane actually found the German fleet – and promptly departed after the German warships opened up on it. Another sighted and attacked a German destroyer. Another spotted the German cruisers Stralsund and Graudenz.

Others wandered around lost, eventually jettisoning their bombs to lighten their load. The Germans reported one 20-pound bomb struck a Zeppelin shed. It is believed it was one of the jettisoned bombs, a lucky, accidental hit.

Of the seven aircraft used, only two returned to Britain, recovered by the seaplane carriers. One ditched near the Netherlands, its crew recovered by a Dutch trawler. Three others landed near British submarines. The planes were destroyed, but the crews saved.

The High Seas Fleet left the three seaplane carriers, and their covering cruisers and destroyers unmolested. As the British fleet withdrew it was attacked unsuccessfully by German Zeppelins and naval floatplanes.

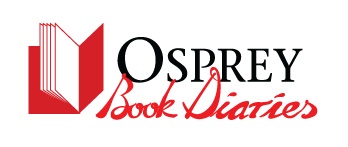

Loading seaplanes on Engadine and Riviera prior to raid

The raid’s best-known participant was Erskine Childers. The author of spy thriller The Riddle of the Sands was a lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve in 1914. He flew aboard one of the raiding aircraft as an observer.

The Cuxhaven Raid may have accomplished little. Regardless it was the ancestor of the great carrier strikes of World War II such as Taranto, Pearl Harbor, or the massed Allied carrier raids on the Japanese home islands.

| Previous: Some dazzling profiles | Next: Battlescenes |

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment