Three questions that one might ask me about Combat 54, US Soldier vs British Soldier: War of 1812 are: (1) Why did you pick this subject? (2) Having done so, why did you pick the three actions profiled? and (3) What is your conclusion? I will attempt to answer these here.

The first question has several answers. First, the bicentennial of the war occurred a few years ago, which caused me to read several recently published books and some reprints of books and monographs originally written during the war or shortly thereafter. I also read sections of collections of documents for the war. Second, I have always been interested in how armies (and navies) are organized, trained, equipped, supplied in the field, how they develop and use tactics, and how they respond to failures in any of these and seek to improve. Third, I came to the conclusion that the experiences of the US Regulars during the war provided a case study; it became clear that defeats at the hands of the British forced the US Army to learn how to fight.

The three actions profiled were selected to show the evolution of the US Army during the war. These are located along the Niagara and St. Lawrence Rivers. This region, the Northern Theater to the Americans, was where the two main armies faced off for two and a half years. The actions are: the failed American attack at Queenston Heights in 1812 made by raw troops, an embarrassing defeat by a much smaller British force at Chryslers Farm (along the St. Lawrence) in late 1813, and the hard-fought draw between two roughly equal forces at Chippewa in 1814.

What stood out is that compared to the British Army, the US Army in 1812 was amateurish. This is made clear when looking at the officer corps. Rapid expansion of the number of US Army regiments in 1812 and in later years, resulted in the majority of new regimental and company officers being commissioned directly from civilian life. These men owed their positions to political connections or nepotism. New regiments lacked trained junior officers and experienced non-commissioned officers to teach and oversee training, drill, and combat. A US Armyofficer’s professional knowledge was dependent upon his own studies. Some used various European texts to learn about their profession. These self-educated officers provided the men who became successful leaders. One such Regular was Winfield Scott, who acquired and studied his own library of military texts. Scott later described the Regular officer corps in caustic terms. He wrote that the pre 1808 officers were generally lazy, ignorant, or drunk while most of his fellow officers appointed in 1808 (when Scott was commissioned as a Captain) were unfit for military duties. He said the same about most of the new officers commissioned during 1812 and 1813. For officers and men, actual war would be their schooling.

In contrast the British Army in 1812 had a much more professional officer corps and a solidly experienced body of NCOs. Two-thirds of the infantry officers were products of the purchase system, while the other third were a mix of men who had initially purchased a junior commission and were subsequently promoted for their service, or commissioned from enlisted and NCO ranks, usually for heroism in action. Although the former enlisted men were seldom promoted beyond lower officer ranks, they provided a cadre of experienced combat leaders. As the world-wide war against Napoleon continued, combat, overseas deployments, and sickness weeded out dilettantes and incompetents, causing the numbers of officers with non-purchased commissions to increase in battalions at war and in overseas garrisons such as Canada.

Reforms directed by the British Army’s Commander in Chief, The Duke of York (served 1795–1809 and 1811–27), had improved the officer corps and the treatment of the enlisted men. Regulations were introduced aimed at preventing purchase of commissions as captains and majors by young inexperienced men. Efforts were made to prevent incompetents from being promoted and to require that officers demonstrate that they knew their jobs. These reforms created the army that the Duke of Wellington led to victory in Portugal and Spain and the army that fought the US Army in North America.

A War of 1812 battle was primarily an infantry fight and therefore infantry drill and tactics were critical. The British started the war with the distinct advantage of having a well-disciplined, well-trained, cohesive force. The Duke of York ordered that British Army doctrine was common throughout the Army and based on one standard manual: Rules and Regulations for the Formation, Field-Exercise, and Movements of His Majesty’s Forces. This was originally issued June 1, 1792 and updated in 1803, 1804, and 1809. The Army thus had a uniform repertoire of formations, movements, and actions, and the commands necessary to execute these. All British troops understood these commands. These regulations were based on the British preference for linear fighting that maximized the effectiveness of smoothbore muskets on a battlefield.

In contrast, the US Army suffered doctrinal indecision and political machinations that resulted in three separate manuals. The first and oldest manual was the War of Independence era Blue Book of Baron von Steuben. This was based upon mid-18th-century European doctrine which was simplified for non-professional, less extensively trained, US Army and militia personnel. In early 1812 the War Department ordered the Regular Infantry to adopt a manual by Alexander Smyth. Smyth’s manual was an abridgment of 1791 French Infantry Regulations for battlefield doctrine and von Steuben’s rules for camps. After Smyth's failure as a general in 1812, the War Department ordered the use of a third manual, William Duane’s A Handbook for Infantry. Like Smyth, Duane borrowed from the new French manual and von Steuben. Unfortunately, Duane was no improvement over Smyth. The result was officers in the field used whichever of the three they wished, in whole or part. Several US Army regimental commanders avoided all three manuals and used the British regulations. This confusion did nothing for higher-level cohesion.

After a string of US defeats in 1812 and 1813 new generals were put in command of the Northern Army in early 1814. The new commander, Jacob Brown – a former New York militia officer who had performed extremely well during 1813 – placed his subordinate, newly promoted Brigadier General Winfield Scott, in charge of training. Scott immediately instructed all regiments to use an abridged version of the French manual and started daily training, ranging from individuals to brigade and division drills. Regimental officer ranks were purged of incompetents, staff officers either learned their duties quickly or were sent home. Brown and Scott's work resulted in the Americans meeting the British on a traditional open battle at Chippewa on July 5, 1814. The British saw that these Americans were not the untrained amateurs of the last two years. The two brigade-sized forces fought to a draw with the British retreating. This action showed that the US Army had learned how to stand and fight as regulars from its past defeats in the hard school of combat. Their teachers were the best in the world, the British Army.

My answer to the third question - what is my conclusion? is simple. After researching and writing Combat 54, if one asks me who I think of as the father of the US Army, I will reply, "Winfield Scott", then add, "and its grand uncle was the Duke of York."

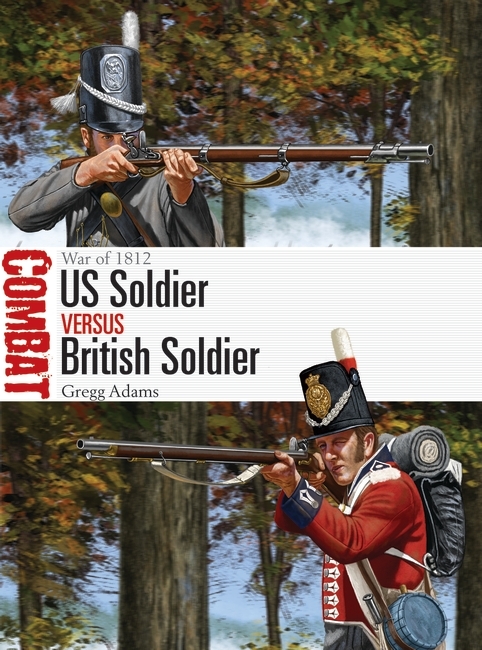

US Soldier vs British Soldier publishes 18 February. Preorder your copy from the website now!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment