In his second blog, William Shepherd gives a flavour of the ‘ancient voices’ he built his new book, The Persian War in Herodotus and Other Ancient Voices, around.

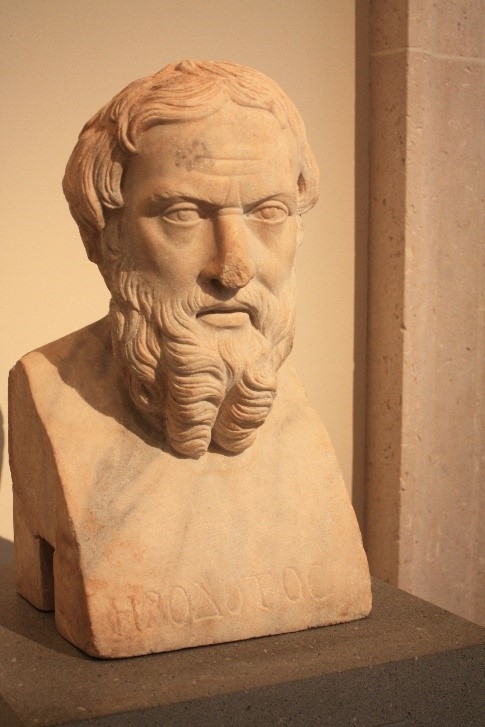

Far more Greeks heard Herodotus’ Historia performed by him in his time than read it from a manuscript. This is how he started his performance, probably quite often to a paying audience:

Herodotus of Halicarnassus presents this Historia to ensure that the events of mankind should not fade in memory over time and that the great and marvellous deeds performed by Hellenes and Barbarians alike should not go unsung, and, additionally, to explain the cause of the war that they fought against each other. (1.1)

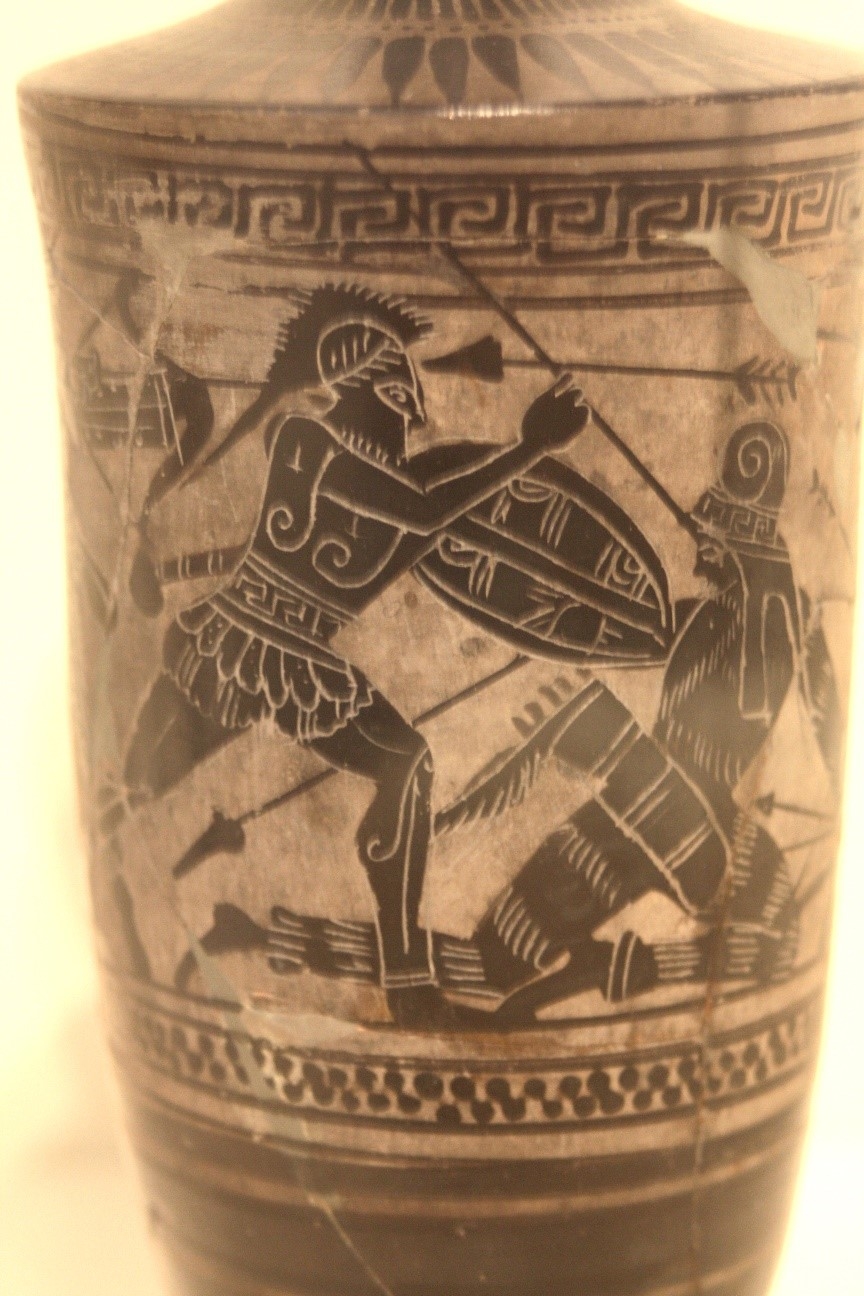

Marathon in 490 was the first clash of Greeks and Barbarians on the mainland of Greece. For the Athenians it was immensely important as a matter of identity and pride. The Persians on the other hand could shrug it off as a minor setback at the end of a successful probe across the Aegean, a temporary delay of the Great King Darius’ plan to extend his empire into Europe and from there to the setting sun.

Herodotus’ account of the battle, just a few hundred words, is the fullest we have. This is his description of its turning point:

The fighting went on for a long time at Marathon. The Barbarians were winning in the centre where the Sacae and the Persians themselves were positioned. They were winning here and broke the Greek centre and drove it inland. But on each flank the Athenians and the Plataeans were winning. They let the routed Barbarians run and wheeled each wing inwards to attack those who had broken through in the centre, and then the Athenians were victorious. The Persians turned and ran, and the Athenians came after them, cutting them down until they reached the shore. (6.113)

Later sources wrote about this battle with rather more excitement and invention. Justin here lavishly embroiders the story of the tragedian Aeschylus’ brother losing a hand and his life in the fight around the Persian ships.

After killing a great many in the battle and chasing the fleeing enemy to their ships, Cynegirus seized a fully manned trireme with his right hand and would not let it go till he had lost that hand. Even then, with his right hand cut off, he held onto the ship with his left. When he lost this as well, he finally hung onto the ship with his teeth. He had such fighting spirit that, unwearied by so much killing or by the loss of both his hands, but defeated and dismembered, he fought on with his teeth to the last like a wild beast. (Justin Epitome of Trogus’ Philippic Histories 2.9)

Surely the inspiration for the Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail!

Robert Browning became even more excited:

Run, Pheidippides, one race more! the meed is thy due!

‘Athens is saved, thank Pan,’ go shout!” He flung down his shield,

Ran like fire once more: and the space ’twixt the Fennel-field

And Athens was stubble again, a field which a fire runs through,

Till in he broke: “Rejoice, we conquer!” Like wine thro’ clay,

Joy in his blood bursting his heart, he died — the bliss!

The Great King Xerxes inherited this unfinished business and led the Persians back into Greece in 480. Thermopylae was the land segment of the Greeks’ first line of defence; the simultaneous sea battle of Artemisium off the north coast of Euboea was far bigger and much more significant. Thermopylae is on a par with Marathon as the best-known of the six battles of this war and for the mythology that grew rapidly around it, and it’s almost as much written about; but, like Marathon, it is actually less important than the sea battles of Artemisium and Salamis, and the decisive land battle of Plataea.

We rejoin Herodotus at Thermopylae on the third and final day when the 300 Spartans (and several hundred other Greeks who tend to be overlooked) fight their doomed rearguard action to cover the retreat of the rest of Leonidas’ blocking force.

The Hellenes fought with all their strength and with reckless fury, knowing very well that death was closing in on them, brought by the force that had come over the mountain. By this stage in the battle most of their spears were broken and they were killing the Persians with their swords. And, in the thick of this, Leonidas fell, his excellence proved, and with him fell many other famous Spartans… There was a mighty struggle between the Persians and the Lacedaemonians over Leonidas’ body, and the Hellenes finally dragged it away after four times heroically driving the enemy back. (7.24)

This is the stuff of Homer, and the Greeks were still spiritually quite in touch with the warrior heroes of the Iliad. Many reflecting on Leonidas’ sacrifice would have been reminded of Achilles’ death and of the way he faced it, and even known these words:

My doom I will accept whatever time it is the will of Zeus

Or other immortal gods to bring it on.

Not even mighty Heracles escaped his doom.

Most dear he was to Zeus, Cronos’ son, the king,

But fate and Hera’s fierce anger broke him.

And so, I too will lay me down to sleep in death

If a like fate is wrought for me.

But for now, let me win high renown …

For all your love for me, do not try to hold me back from battle

Or change my mind.

(Iliad 18.115–121, 126)

Later in the year the two sides met again, further south and on the sea at Salamis and Aeschylus was there, though on his death he wished only to be remembered for fighting at Marathon (and not for his supreme tragedies either). His Persae is the nearest thing we have to a first-hand eye-witness account of the Persian War. This is a Persian messenger speaking:

As soon as the white colts of daybreak,

Brilliant to behold, covered the earth,

A cry rang out from the Hellene ranks

Like a triumph song, and a high echo

Bounced back from the island rocks.

Terror gripped the Barbarians,

Terror and shattered hopes. This was not flight!

The Hellenes were singing their sacred paean

And surging into battle with spirits high.

A trumpet call set them all afire.

Straightway, on the command, they dipped their oars,

All striking the ocean brine together.

Swiftly the whole fleet came into view,

The right wing leading in perfect order

And then the whole host coming out against us.

And we could hear a great shout,

‘Sons of Hellas, forward to freedom!

Freedom for the land of your fathers!

Freedom for your children and wives!

Freedom for the shrines of your ancestral gods,

For the tombs of your forefathers!

Now all is at stake!’ …

At first the great stream of Persian ships held its own,

But, when the mass of them crowded into the narrows,

Far from giving support, they crashed into each other

With their bronze-beaked prows shattering all their rowing gear.

The Hellenes systematically worked their way around them

And struck from all directions.

(386–405, 412–417)

Writing towards the end of the century, when Athens was out for the count in the Peloponnesian War, Timotheus wrote an elaborate ode, also called the Persae. It was chanted over a strummed lyre and full of extravagant metaphors and purple vocabulary. But we are right there, on the straits of Salamis, pulling away at our oars and unable to see anything much of what is going on, least of all in front of our trireme, and we are rammed …

Spray flying from the oars,

The fleets sweep together

Ploughing through the swell

Ram teeth bared.

They close, and curving prows

Rip through the fir-tree limbs.

A strike on one side shatters oars

And throws the rowers all one way.

Then, on the other side, a second strike

Smashes more banks of oars and seafaring pine

And hurls the rowers back again.

(1-11)

Back to Aeschylus:

Capsized hulls covered the open water

Clogging it with wreckage and the dead.

The shores and reefs were draped with corpses.

Every ship was flying in chaos,

Every ship, that is, in the Barbarian fleet.

The Hellenes, like fishermen netting tuna or some other haul of fish,

Battered and skewered with broken timbers and splintered oars,

And screams and groans filled the salty air

Until black-eyed night brought the horror to an end.

(418–428)

Xerxes sailed home with his fleet, never to return, but a very large army stayed behind under the command of a royal prince, Mardonius. Aeschylus sets the scene and points the moral in a prophecy delivered by the ghost of Darius.

… Vain hope drove Xerxes

To leave those chosen troops behind.

Utter disaster lies in wait for them,

Payment of the price of their impious acts and godless thoughts.

For, when they reached the land of Hellas,

Without shame they ravaged sacred images and set temples ablaze.

Altars were smashed, holy shrines ripped from their foundations

And tumbled into shambles of shattered stone.

Such evil have they done, so great will be their suffering.

And more will follow; their river of pain is not dry, still it gushes.

The Dorian spear will make Plataea’s soil a bloody swamp

And heaped up-corpses will send to mortal men,

Even the next three generations, this unvoiced message:

You are mortal, do not think over-mighty thoughts.

For, when hubris has blossomed and ripened on the bough,

It yields a bitter harvest of delusion.

(800–822)

We jump with Herodotus to the final day and climax of the twelve-day battle of Plataea fought in Boeotia, ‘the dancing floor of Ares’. Around 200,000 men were involved in this battle for the future of western civilization, about the same number as at Waterloo, alive and dead after Blücher had arrived, and rather more than fought at Gettysburg or were shipped over the Channel on D-Day.

The dancing floor of Ares’

The Persians set aside their bows and faced up to the Hellenes, and at first the fighting was along the wall of shields but, when that went down, there was a hard struggle around the sanctuary of Demeter. It went on for a long time because the Barbarians kept seizing the Hellenes’ spears and breaking them. The Persians were not inferior in courage or physical strength, but they were not armed like hoplites or trained in their way of fighting, and they did not have the tactical skill of their opponents.…

Wherever Mardonius was fighting, mounted on his white charger with his picked band of a thousand, the flower of the Persians, there they pressed the enemy hardest. And while Mardonius still lived, they held their own and, fighting back, struck down many Lacedaemonians. But when Mardonius had fallen and when the men around him, the best in his army, had been slain, then the rest were put to flight and gave way before the Lacedaemonians. Their greatest disadvantage was the lack of armour in their equipment. They were, in effect, naked men battling with hoplites….

And on that day, in accordance with the oracle, due compensation was fully paid by Mardonius to the Spartans for the killing of Leonidas, and the most glorious victory ever known was secured by Pausanias, son of Cleombrotus, son of Anaxandridas.

(9.62,64)

Order your copy of The Persian War in Herodotus and Other Ancient Voices here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment