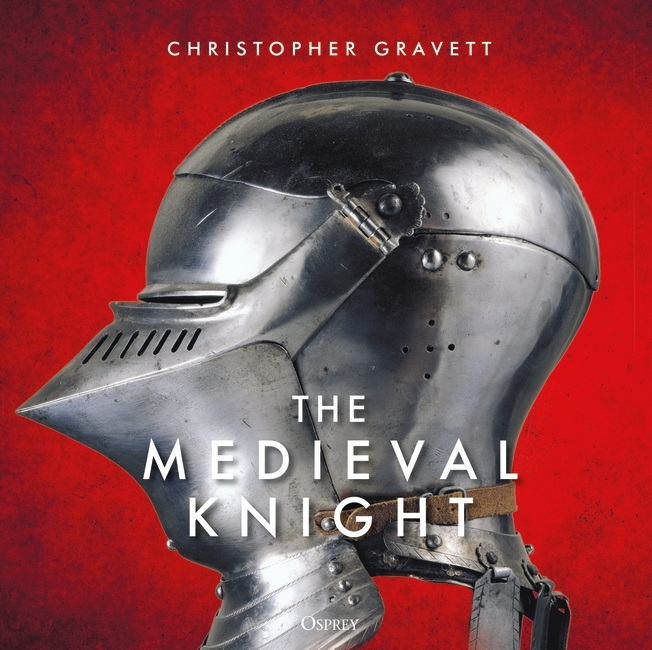

On the blog today, Christopher Gravett, author of the beautifully illustrated The Medieval Knight, shares how his fascination for this period came about and gives a brief overview of the book.

Four of my Warrior titles for Osprey were merged in 2008 to produce a single work entitled 'Knight', which covered knighthood in England from 1200 to 1600. This new volume concentrates on the medieval English knight from 1200–1500.

I first became interested in medieval history as a teenager and this was cemented in 1966 when I attended celebrations to mark 900 years of the Norman Conquest down at Battle in Sussex. I was fortunate to be able to steer my career into the world of curating, obtaining a masters degree in Medieval Studies and obtaining positions working with the fabulous objects in the British Museum before moving to the Royal Armouries at the Tower of London, where I was able to see and handle at first hand some of the best examples of medieval and later armour and weapons. This allowed me to understand how armour works, to feel its weight and the balance of a sword in the hand, and also gave me the opportunity to wear replica full plate armour for demonstrations of arming. When the audience was of the opinion that it must be so heavy that you couldn’t move properly in it, it was very rewarding to then drop to the floor and promptly get up again unaided, making the point that I was an ageing curator, not a fit trained young knight. Such a demonstration of agility also dispelled the myth that knights needed to be winched into the saddle, as portrayed in some films.

Holding real mail at first came as a surprise after having handled some replica examples made from much thicker wire and therefore far too heavy. I was fascinated too by plate armour and the skill displayed in creating a sculpture in steel that not only had to protect the man inside but allow him to move, achieved by shaping individual pieces so they slide over or pivot on each other. Moreover, the metal itself varies in thickness to enable the weight to be kept down, the thickest areas reserved to protect the most important parts of the body such as the chest and top of the head. The smooth surfaces provide glancing contours to deflect weapon points and even two plates overlap away from a weapon so it does not become caught in the joint. I was lucky enough to be able to watch modern armourers at work (even try my hand at making a piece) and observe the skill and great physical effort it takes to form the steel plates.

Much armour dating before the 15th century has been lost and it was sometimes amusing to find that visitors to the Royal Armouries thought there must be cupboards full of 12th-century mail coats, when in fact there are virtually no complete early examples in Europe at all. This lack of early material means falling back on contemporary descriptions or pictorial depictions in manuscripts, or on sculptures and effigies. Visiting churches, cathedrals, museums etc, often during holidays, has allowed me to amass photographs, and working in national museums gave me the opportunity to study some beautiful manuscripts. I have always found trying to interpret this evidence to be a thought-provoking exercise, especially when the armour is sometimes partly concealed under outer layers. Unfortunately 15th-century English plate armour does not survive in any quantity so must be reconstructed, especially from effigies, which give a three-dimensional view and show the differences from that produced in the great centres in Germany and Italy, which happily do survive in larger quantities.

The Head of Interpretation at the Armouries once commented while we were filming a re-creation of a club tournament at Bodiam Castle that it was so useful to have in one place specialists in horses, in armour making, in tournament history and in re-enacting the event, all pooling their knowledge for the finished product.

I became especially interested in the tournament, a subject often poorly understood and unfortunately often misrepresented in film portrayals. At first literally a battle between two groups of knights with the idea of taking captives for ransom, the tournament was also practice for war. However, it began to include individual contests called jousts, enabling two contestants to show off their skill. A variety of courses was introduced, increasingly set about with rules, and I made a study of one detailed French manuscript describing a tourney with clubs, in order to present a lecture to the International Medieval Congress at Kalamazoo.

I also studied the early development of special tournament armour pieces designed to provide for extra safety (again largely from pictorial evidence, since most surviving tournament armour dates from the late 15th century onwards) in order to give a talk at the opening of a tournament exhibition in Stockholm. Increased protection came at the expense of practicality, as it sometimes restricted movement or vision.

Great pageants developed during the 14th and 15th centuries, more especially in places such as Burgundy, often fortunately being fully recorded. English knights joined others from all over Europe at such gatherings, hoping to show their skills and win renown and prizes. Here chivalry was evident, as knights and squires vied to impress the ladies in the stands, but I have to make the point in the book that at first the term simply meant horsemanship (from the French ‘cheval’ for a horse). By the 13th century the concept of chivalry had grown to embrace respect for women, courtly love, protection of the weak and of the Church. The latter, in its efforts to try to tame the violence inherent in men trained for war, also encouraged the vigil at the altar before dubbing into the ranks of knighthood. However, I have to highlight the fact that many knights fell short of the ideal chivalric warrior. Some were basically rough mercenaries and others preferred to stay on their estates, attending shire courts as required. Latterly some men remained squires, well taught and trained and effectively knights in all but name.

The gaudy panoply of heraldry that identified a knight and may have begun in the tournament is something I have always been attracted to, so much so that I joined the Heraldry Society and obtained their certificate. I find that the terminology is rather like riding a bike: once learned you don’t forget it.

The book covers the transformation of English armies from the feudal host that served for a set period in return for land – with its drawback apparent when kings required prolonged campaigns (especially abroad) – to armies recruited by contract. The latter developed towards the end of the 13th century, with troops paid for an agreed period of service, enabling knights to be gathered who would stay the course. This proved ideal during the Hundred Years’ War as English armies moved through France. Following the end of the wars in France in 1453, the Wars of the Roses saw the most powerful English nobles fielding private armies of their own.

Perhaps surprisingly, the numbers of knights and squires in an army could be quite small compared to other troops and their numbers tended to decrease as the centuries progressed. For Edward IV’s 1475 expedition to France, for example, one knight might bring up to ten men-at-arms and 100 archers. In the 13th century, knights were often mounted but could be ordered to dismount if tactics required it, to stiffen the ranks of the foot. In the following centuries, English kings increasingly dismounted many or all of their forces, ideally choosing a good position and waiting until the enemy attacked, weakening him with arrows and funnelling him onto the knights and men-at-arms. This served the English well in France in their great victories at Crécy, Poitiers and Agincourt; I was fortunate to be invited to the opening of the then new museum at the latter.

Agincourt is just one of many battlefields I have trudged over, even giving talks on the field of Hastings at Battle Abbey on the 950th anniversary of 1066. In my younger days I had re-enacted and had a taste of combat, formed shield walls and felt the thud of weapons on shield and helmet. I had joined a local archery club and appreciated the power of even modern target arrows, never mind the war arrows used in the past. Fighting causes casualties and I cover the sort of treatment that might be expected, which depended on a man’s rank and often on luck.

Despite all the hard training, major battles were infrequent as they were highly risky and a single defeat could spell ruin. Although England was strewn with castles, sieges were relatively infrequent but also took place in our wars across the Channel, the techniques used being mentioned in the book. The final chapter looks at the effects of gunpowder, at changing tactics on the battlefield, at social change, and how the knight has adapted and survived into the modern era.

The Medieval Knight publishes today! Order your copy from the website now.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment