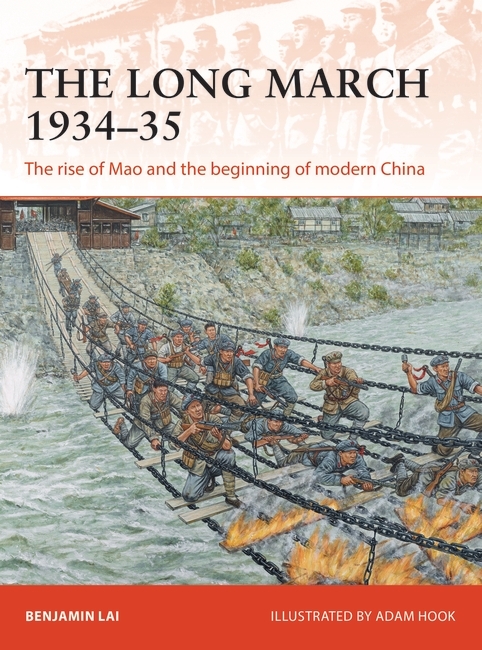

Today on the blog Benjamin Lai, author of The Long March 1934–35, writes about a chapter of history, although much revered in China, the details, and especially military aspect, of this campaign was largely ignored in the West. This book is the first book in English to tell the story of the Long March from a military angle.

The Long March was a strategic retreat undertaken by the Chinese Red Army when being pursued by hordes of government troops. The escape was not only moving its soldiers but their families as well as the supporting staff , as well as all they could take, including the ’kitchen sink‘ from its hideouts in the mountains to a safe haven in the desert plateau in Shaanxi-Gansu in north-west China. It was not a single march but a march by five armies, the First, Second, Fourth Armies, the Seventh Corps as well as the Twenty-Fifth armies, some 304,000 men, women and children. At the end almost two years later, approximately 25 per cent reached the safe haven.

Since that time, the focus of historians and armchair generals when discussing this campaign had been on the reality and facts surrounding the actual march. One of the much-debated points about the Long March was how far did Mao and his armies did walk?

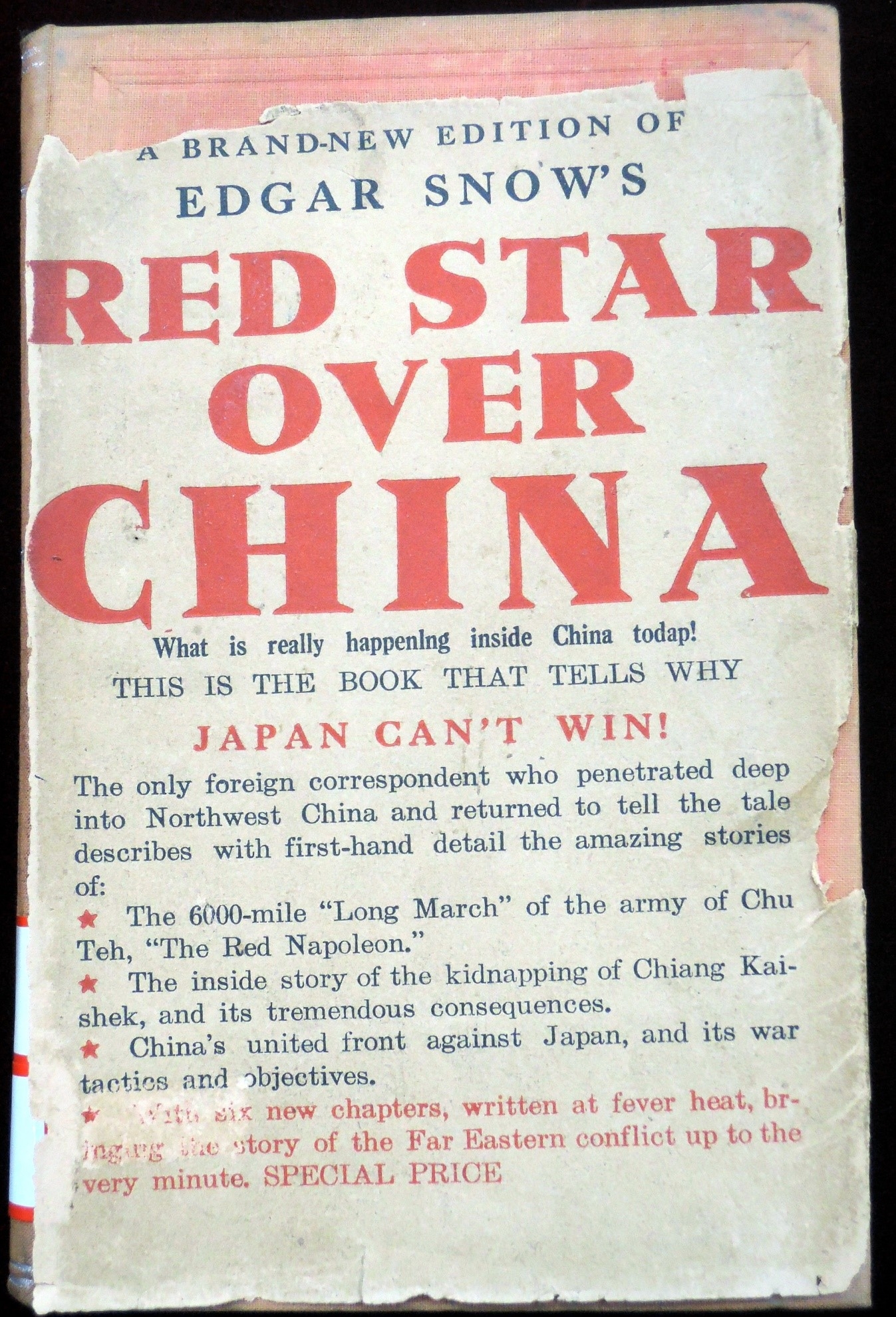

When the West first heard of this event, it was through the pen of Edgar Snow, a leftist American journalist who made the journalist coup of the day by actually interviewing Mao in his rebel safe haven. It was akin to getting a face-to-face interview with Osama bin Laden in the modern context. Edgar asked Mao how far did he walk? ‘Ah,’ said Mao, ‘I don’t know let me think’. After a longish paused, he concluded that he must have walked 25,000 Li. This number was collaborated by Xiao Feng, the Commissar of the First Army headquarter detachment. He wrote in his diary: ‘One day after arriving at the safe haven, Mao told me to collect data from the regiment headquarters of the First Corps, and I presented to him that according to my best estimate the First Army had covered about, 25,000 Li, the longest distance of all the Red Armies’. In Xiao Feng’s dairy, he uses the word Li, a Chinese unit of distance. The trouble with Li is that until the mid-1980s, there was not an agreed standard of measurement. In 1936 when Snow interviewed Mao about the Long March, the Chinese Li can be anything between 500–550 m.

Last meeting between Mao and Snow December 1970; on the rostrum overlooking Tiananmen Square in Beijing. Mao was using Snow to give a signal to Nixon, that Americans are welcomed to China. After much work behind the scene, in 1972, Nixon was the first American President to visit China.

The result of Snow’s journalistic coup – the world first western journalist to interview Mao.

Furthermore, when Mao was on the run during the Long March, for much of where he went the Red Army did not have a map of the area and how many kilometres they walked depended on what the farmers told them. Being illiterate, they counted the distance by hours rather than length – you usually will get there by sunset, if you don’t have a cow with you.

In October 2002, two British writers, Ed Jocelyn, who had a PhD in History, and Andrew McEwen, his friend from Essex University, set off to retrace the Red Army's footsteps and record the experiences. According to McEwen, he recorded his retracing of Mao’s journey as 3700 miles or 6000 km, not 8000 miles (or 13000 km) as what is officially registered by Chinese historians. The undertone of this was that the Chinese told a lie. However, the interview was misleading as the journalist did not include McEwen and Jocelyn’s footnote to this claim. In 2002 much of their walk was on modern tarmac paved road while Mao walked on mountain tracks. To avoid the much superior government troops, the Red Army often had to double back and take indirect routes to hide. Usually, the Red Army just didn’t know where they were! Modern Chinese historians are still debating the original track taken as some of the landmarks written in the diaries were simply in the wrong place. In 2005 in his 70th year, veteran Mossad agent turned businessman David Ben Uziel, retraced the path of the III Corps (commanded by Peng Dehuai – who was better known in the West as Commander of the Chinese Forces during the Korean War), part of the First Army (Mao’s force), and recorded more than 12,500 km if he kept off modern roads.

While we may never know exactly how long the Long March was, it was certainly a very long trek. Mao and his followers battled not only an enemy that was hot on their tail but the elements, disease and hunger. This is a story of how a ragtag rebel army wearing straw sandals and equipped with hand-me-down weapons beat a government force ten times their size, with all the modern weaponry of the day, including aeroplanes.

To learn about how Mao rose from obscurity to become a man who would dominate the 20th century, preorder up a copy of CAM 341: The Long March 1934–35: The rise of Mao and the beginning of modern China.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment