Today on the blog, we're sharing an extract from 'The Franco-Prussian War: 1870-71' by Stephen Badsey.

© Osprey Publishing 2022

The battle of Sedan on 1 September, unlike Gravelotte-St Privat, was a foregone conclusion: numbers, firepower and morale were all on the Prussian side. Two Prussian armies, totalling 224,000 troops, attacked a demoralised, disorganised and exhausted French army half their size. Nevertheless, the French once again made a hard fight of it, holding strong positions with I and XII Corps facing east, VII Corps facing west and north, and the battered V Corps held in reserve; and once again Moltke did not so much direct the attack as fail to restrain his corps commanders.

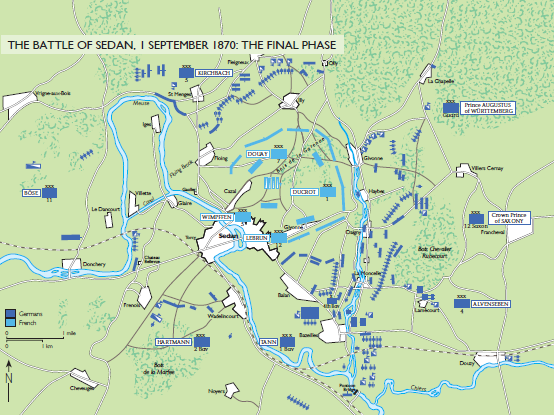

At dawn, in the early mist that later gave way to bright sunshine, I Bavarian Corps came over its bridges at Bazeilles and attacked XII Corps, driving it out of the burning village. In the firefight, there were conflicting claims that the Bavarians had massacred French civilians at Bazeilles or that the French had armed civilians contrary to the laws of war – once more a sign of the future. As XII Saxon Corps arrived in the course of the morning, with IV Corps behind it, the French were driven back into Sedan. At the same time, the Prussian XI Corps crossed the river at Donchery and moved forward, with V Corps behind it coming round to the north to seal off the Belgian frontier, linking hands with the Prussian Guard coming up from the east.

MacMahon had given his army no particular orders for 1 September, apparently expecting another rest day. Riding forward to the fight at Bazeilles, he was wounded and carried back to Sedan, relinquishing command to General Auguste Ducrot of I Corps, who at once ordered a retreat and breakout westward. These orders were immediately countermanded by General Emmanuel de Wimpffen, recently arrived from Paris with instructions from Palikao to take command of V Corps and to succeed MacMahon if necessary. The resulting argument between the French generals added to the confusion, but made little difference to the battle’s outcome. By midday the Army of Châlons was trapped in Sedan with the Prussians on the heights all around.

The Prussians, Bavarians and Saxons had no need to send their infantry forward. Instead they brought up their massed artillery of nearly 500 guns which fired into the town and French positions. King Wilhelm watched the battle from a rise near the village of Frenois just south of the river, accompanied by Bismarck, Moltke, Roon, and the crowd of dignitaries and functionaries with Royal Headquarters. On the other side the Emperor Napoleon, who was almost in a state of collapse from bladder pain, rode from one unit to another, apparently seeking death in battle. Under the weight of Prussian artillery the French gave way in each critical village: Illy on the dominating heights to the north fell early in the afternoon, followed by Floing to the west.

In desperation, the French launched their remaining cavalry division in repeated charges against the Prussians at Floing, attempting to clear a path for the rest of their forces to escape. Each time the Prussian line held firm, the French re-formed and charged again, suffering heavy losses with each charge. ‘Ah! Those brave men!’ King Wilhelm wondered. A story spread that the last few survivors, coming forward to charge again, were saluted by the Prussian infantry who let them pass by to safety.

Within a few hours French resistance began to cease. Troops sought refuge from the shelling in woods or buildings, some trying to get into the medieval citadel of Sedan itself, the gates of which were barred against them. In the wood of Garenne north of the town white flags were hoisted, soon followed by others. At about 5.00pm, Napoleon himself demanded that the fighting should stop and the enemy should be asked for an armistice. The idea of surrender was still too much for some French troops: in the ‘battle of the last cartridges’ more than 1,000 of them stormed into the village of Balan, briefly driving the Bavarians back, but could get no further. A white flag was flown above the citadel and Moltke sent a representative forward to discover its significance. He returned with a message for King Wilhelm: ‘Having been unable to die in the midst of my troops, there remains nothing for me but to deliver my sword into Your Majesty’s hands. I am Your Majesty’s true brother, Napoleon’.

If you enjoyed this extract, why not order your copy of the book from our website here:

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment