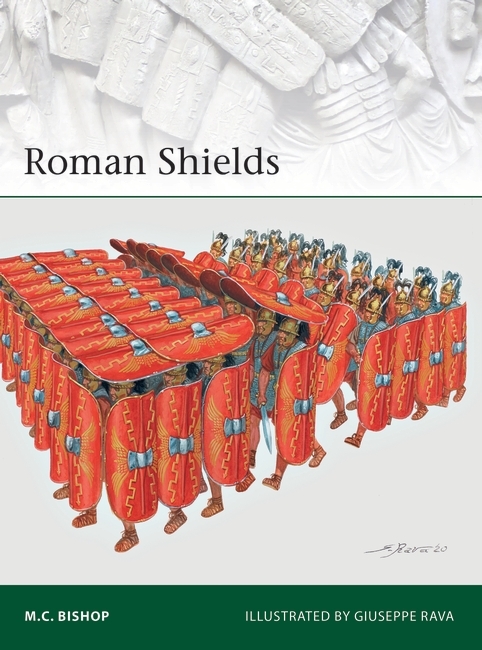

The Roman shield, the scutum, was central to the Romans’ conquest of the known world, and has become an emblem of the legions at the forefront of that effort. This new study draws on the latest research to reveal the history of this iconic equipment. In today's blog post, M.C. Bishop joins us to discuss this tool.

Initially protected by the circular hoplite-type shield, the aspis (which the Romans called the clypeus or clipeus), the legions re-equipped with a new oblong form of shield from the 4th century BC onwards. Known as the scutum (a word which soon came to mean any type of shield), their tactics (and its form) evolved throughout the period of the Republic until it became the large, curved, oval shield depicted on monuments like that of Aemilius Paullus at Delphi in Greece (mid-2nd century BC) or the so-called Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus (late 2nd century BC) from the Campus Martius in Rome (Italy).

With the transformation from Republic to Principate, the legionary shield became smaller and the familiar curved, rectangular form was adopted. Fragments of this type of shield – including bosses – are known from several sites, but it was Dura-Europos (Syria) that has produced a near-intact example of such a shield board, confirming the triple-thickness plywood which written sources suggested was used in its production. Comparison of this 3rd-century AD shield (and those depictions on monuments) with a board from the Fayum in Egypt showed scholars that a Republican-era board also survived, and allows comparison between these two forms of legionary shield.

It is crucial to understand that his shield was as important a piece of weaponry to a Roman legionary as his short sword or pilum. In combat, he not only used it to parry blows but also to inflict them in what was almost a sword-and-buckler style of combat derived from gladiatorial practice in the arena. Moreover, it had an important role to play when throwing the pilum from a stationary position, acting as a counterweight.

Using the shield as a counterweight when throwing the pilum (photo M C Bishop)

Using the shield as a counterweight when throwing the pilum (photo M C Bishop)

The size and shape of the shield also influenced the way Roman soldiers fought. They did not, as Hollywood fondly believes, line up and present a ‘shield wall’ to an approaching foe. Simple mathematics tells us that a shield 0.8m wide would not fill the frontage allotted to a legionary in the battle line but surviving accounts are even clearer as to how the soldier operated:

Now in the case of the Romans also each soldier with his arms occupies a space of three feet [0.9m] in breadth, but as in their mode of fighting each man must move separately, as he has to cover his person with his long shield, turning to meet each expected blow, and as he uses his sword both for cutting and thrusting it is obvious that a looser order is required, and each man must be at a distance of at least three feet from the man next him in the same rank and those in front of and behind him, if they are to be of proper use. (Polybius 18.30.6–8)

The fact that, during the Punic Wars, gladiatorial trainers were brought in to instruct Roman legionaries underlines this extremely personal way of fighting, which required great discipline to perform whilst maintaining formation. Indeed the change in shape and size of the shield in the late Republic and early Principate suggests that it was modified to make it less cumbersome and more versatile in such hand-to-hand combat. Weighing less (between 5 kg and 7.5 kg compared to the earlier 8.5 kg to 10 kg), it was easier to handle, less fatiguing, and gave a better view of the enemy over its upper rim.

Using the testudo to attack a city; cast of a relief from Trajan's Column (photo M C Bishop)

Using the testudo to attack a city; cast of a relief from Trajan's Column (photo M C Bishop)

The nearest the Romans came to a shield wall was the famous (or even infamous) testudo or ‘tortoise’ (both well-protected and slow moving!), a formation developed (and largely used) with one specific purpose: getting close to the walls of a besieged fortification. With shields above, to the front, and to either side, it required legionaries to work as one, abnormally close by their normal standards, and probably required small, lock-step paces (there is no evidence that cadenced marching was normally used by the Romans). A variant involved incorporating a deliberate gradient in the ‘roof’ (low at the back to full height at the front) to enable the boldest soldiers to run up the slope formed in this way and assault defenders atop a parapet (so of limited use against really high city walls!).

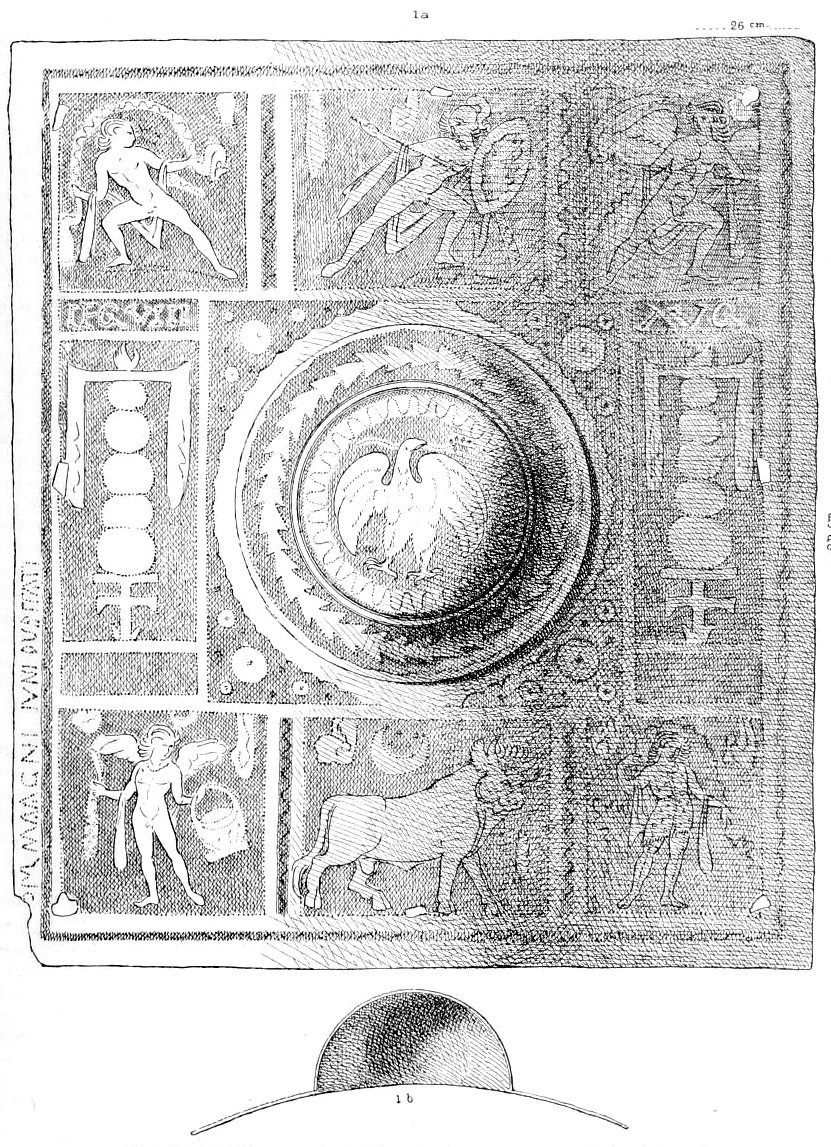

Nineteenth-century woodcut of the Tyne shield boss (photo M C Bishop)

The shield was not only integral to the way a Roman soldier fought, but it was an important part of his identity. Decorated with blazons that were unique to his unit, it also recorded his name and that of his immediate superior – in the case of a legionary shield boss from the River Tyne at South Shields (UK), Iunius Dubitatus in the century of Iulius Magnus of the legio VIII Augusta (which probably visited Britain briefly in the first half of the 2nd century AD).

Auxiliaries with oval shields and equipment stacked on legionary shields; cast of a relief from Trajan's Column (photo M C Bishop)

The flat, oval shields used by many (but by no means all) auxiliary troops under the Principate much more closely resembled those of their most common enemies in northern Europe (the Celtic, Germanic, and Dacian peoples all using similar shields). That they were more versatile than the curved, rectangular shield (which – although the term can sometimes be found – was never truly ‘semi-cylindrical’, since the shield board formed slightly less than 40% of a cylinder), is indicated by the phasing out of the latter in favour of a slightly domed version of the former during the later Principate before the reintroduction of round shield boards under the Dominate, thus bringing the Roman legionary shield full circle (quite literally!) from the Regal period to the Fall of Rome. Curved, rectangular shields continued in use in the 4th century AD, but only as legacy equipment issued to gladiators.

Roman Shields is out now! Get your copy here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment