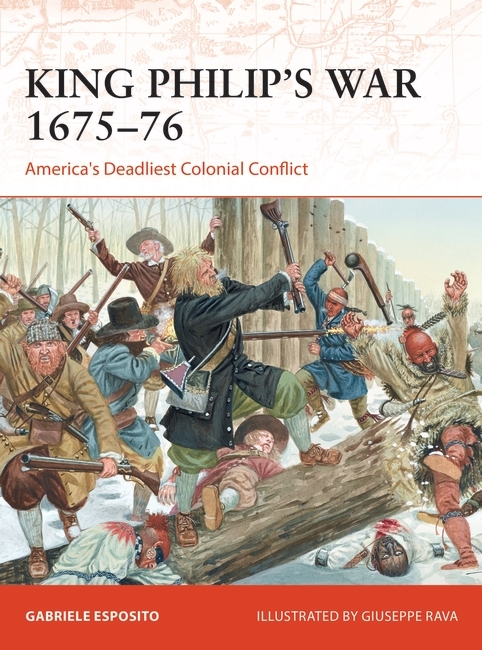

The upcoming Campaign title, King Philip's War 1675–76 looks at the major conflict between the southern New England colonists and the area's indigenous Native Americans, On the blog today, author Gabriele Esposito examines the Native American forces involved in the years preceding the battle and the conflict itself.

King Philip’s War is, without a doubt, one of the lesser-known conflicts in America’s ‘forgotten wars’. This is primarily because it was the first major war ever to be fought on American colonial soil. When the conflict broke out, the idea of ‘America’ as we know it today did not exist. In 1675, the English colonies in the New World perceived themselves as separate communities without a common identity. Each local community had its own interests and an independent relationship with its adopted land. There was no sense of unity, no sense of ‘nation’. After King Philip’s War, all that changed, this was the first time ‘Americans’ had to face a common and deadly enemy and, in the end, they prevailed, but only after uniting all their forces and resources in one single effort.

Metacomet, part of the Wampanoags tribe, wanted the English colonists out of North America. He wanted to destroy the world they had built, which was still in its early development. To survive, the colonists had to act together and they soon realized that their adopted land was not particularly interested in their destiny. In fact, not a single English soldier came to their aid during the war. After 1676, most Americans finally understood that their future lay in their hands and that ideals such as the ‘true’ American spirit, ‘manifesting destiny’ and the ‘frontier’ were important.

The war saw a new way of warfare based on hit-and-run tactics perfectly suited to the environment of the North American woodlands: tomahawk and musket, a deadly combination invented by the natives, was adopted by colonial militiamen with great success; the origins of the future ‘minutemen’ who made America a free nation exactly one century later can be found in its military innovations, and it saw the birth of the famous ‘rangers’: lightly-armed and highly-mobile skirmishers who fought in the same way as their native opponents. In addition, one of the great frontiersman of the time, Benjamin Church, transformed the military identity of the colonies. It also changed the balance of power in English North America. After 1676, the natives were forced to assume a defensive approach in order to survive and had to abandon their dream of expelling the strange white people living in their land.

From the natives’ point of view, King Philip’s War was the first occasion during which North American tribes understood that the only way to defeat white people was to form large inter-tribal alliances and Metacomet was the first warrior chief to do this with his example being followed with varying success by several other great native leaders.

Despite this, King Philip’s War is still not regarded as a key turning point in the perception of colonial settlers and isn’t studied quite as much as it could be. Metacomet, the famous ‘King Philip’ who gave his name to the conflict is generally regarded as just one of the many warrior chiefs who were defeated by the settlers, similar to Pontiac or Tecumseh. .

Metacomet, also known as Metacom, was born in 1638 and was the second son of the great chief Massasoit. His tribe was the Wampanoags, who lived in south-eastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island. The Wampanoags had been the most numerous tribe living in New England before the arrival of the English settlers, numbering several thousand. Together with the Virginian tribes, the Wampanoags were the first native community of North America to have contact with white people. English merchant vessels and fishing boats began to sail along the coast of New England during the early 17th century and, in 1614, some of these English ships captured a certain number of Wampanoags and later sold them in Spain as slaves. One of these named Squanto was bought by a community of monks and later converted to Christianity before being freed. Thanks to his time on English ships and in Spain, Squanto learned how to speak both English and Spanish; and when he returned to England, as a free man he was assigned to an expedition going to Newfoundland (Canada). From there, in 1619, Squanto was finally able to return to his original community. When the Pilgrim Fathers founded Plymouth Colony, he would prove to be invaluable as an interpreter .

When the first English settlers disembarked on the Wampanoags’ land, their leader was Massasoit and Metacomet hadn’t yet been born. Massasoit , seeing that there weren’t many of them, but that they had effective weapons, decided not to attack. At that time, he was fighting other tribes in order to affirm his role as ‘sachem’ meaning ‘supreme chief’ and still referred to great warrior chiefs who exerted their authority over inter-tribal confederations. Massasoit had the idea of using the settlers as powerful allies in his wars against bordering tribes so the Wampanoags taught the English settlers how to cultivate the ‘Three Sisters’ (the three main agricultural crops of New England: corn, squash and beans) and how to catch and process fish which was abundant along their coast. Relations between Massasoit’s Wampanoags and the settlers were so peaceful that in 1621, some members of the two communities celebrated the first ‘Thanksgiving’ in American history together.

In 1632, however, the Wampanoags were attacked by the powerful Narragansett tribe: the Wampanoags and the Narragansetts had always been rivals, but the arrival of white people had worsened the relations between the two tribes. The colonists soon came to the aid of their Wampanoag allies and their help was decisive in repulsing the Narragansetts. It proved that Massasoit’s leadership as a ‘sachem’ was increasingly dependent on the support of his white allies.

As time progressed, relations between Wampanoags and the white settlers remained cordial but then the political situation in New England started to change. In 1643, the Mohegans defeated the Narragansetts and they started moving towards the territory of the Wampanoags; this time, however, the two tribes did not fight but started to cooperate.

By 1650, a good number of Wampanoags, especially women, had been converted to Christianity and Massasoit had learned to live like a settler. During the last phase of his life, the ‘sachem’ even asked the legislators of Plymouth Colony to give English names to both of his sons: the older one, Wamsutta, was given the name Alexander; Metacomet, instead, was given the name Philip with which he became famous.

Wamsutta had the same ideas of his father and wished to continue having good relations with white people; Metacomet, instead, had a completely different vision of the world and was strongly convinced that the settlers had no right to stay and live on the land that had always belonged to the Wampanoag tribe. In 1661, when Metacomet was 23, Massasoit died. Wamsutta, as expected, became chief of the Wampanoags. Shortly after, Wamsutta was forced by the colonial authorities to go to Marshfield in order to be interrogated by the Governor of Plymouth. The settlers were worried about the intentions of the new chief and feared that he would revolt against them. The meeting was positive, but while coming back to the village, Wamsutta became seriously ill and died shortly afterwards.

The Wampanoag chief probably died of fever but many of the Wampanoags thought that he had been poisoned by the settlers. In 1662, less than one year after Massasoit’s death, Metacomet became chief of the tribe and assumed the role of ‘sachem’. Under his new leadership, the usual attitude of the Wampanoags towards the English settlers changed dramatically. Metacomet, who had been brought up as an exemplary woodland warrior, strongly believed that, with the progress of time, the settlers would eventually take away everything from the natives. Not only their lands, but also their culture and traditional way of life. The only way to stop this process was to create a large coalition of tribes who would be strong enough to conduct total war against the foreigners with the objective of expelling them from New England.

As ‘sachem’ of the Wampanoags, Metacomet was the supreme military native commander during the war of 1675-1676; the warriors under his orders, however, came from several different tribes and so had their own chiefs who played an important role during the conflict. The most important and capable of these was Muttawmp, leader of the Nipmucs. This tribe had converted to Christianity, and Muttawmp was one of many ‘praying Indians’ present in each tribe. After becoming chief of the Nipmucs, Muttawmp gradually changed his attitude towards the English settlers and assumed the same political position as Metacomet. In 1675, when King Philip initiated his offensive against the white people, Muttawmp was one of the first leaders to join his attacks and even foreswore Christianity. Like Metacomet, Muttawmp had been educated as a warrior since his childhood and had great fighting experience. It was him who led the native warriors during some of the most important battles that took place during King Philip’s War: Wheeler’s Surprise, the Siege of Brookfield, the Battle of Bloody Brooke, the Hatfield Raid and Sudbury Fight.

From a military point of view, Muttawmp was Metacomet’s main ‘field commander’ and proved to be an excellent tactician. He was a master at organizing ambushes against colonial militiamen and had great knowledge of the terrain on which the war was fought. By using hit-and-run tactics, Muttawmp was able to win several victories and cause heavy losses to settlers. At the end of the war, after King Philip’s death, he tried to make peace with the colonists but was captured and executed for war crimes (which included the killing of numerous civilians).

Another important warrior chief who fought on Metacomet’s side was Canochet of the Narragansett tribe. He was an experienced fighter but was defeated by the colonists during the so-called ‘Great Swamp Fight’ with most of his warriors. In contrast to his predecessors who had fought on several occasions against the Wampanoags, Canochet decided to support King Philip in his war and remained loyal to the native cause until the end of the conflict. In 1676, he was captured by colonists and later executed, after refusing to surrender.

Generally speaking, each tribe was guided by a council of elders that took all the most important political decisions. Made up of old men of great experience, the councils were usually contrary to military expeditions directed against the settlements of white people, however, inter-tribal warfare was something accepted with no problems by all members of the community. The youngest warriors of each tribe who were not part of the council, generally favoured a strong anti-foreigners policy which could sometimes cause significant internal clashes inside a tribe. The case of the Wampanoags is typical: Massasoit continued to treat the English settlers as friends until the end of his life, while his son Metacomet attacked them as soon as he became ‘sachem’.

During the middle decades of the 17th century, the numbers of the native population in New England declined greatly, mostly because of the epidemics imported by the European colonists. This caused great resentment among various tribes who envisaged a bleak future. As a result, an increasing number of young warriors started to organize raids against the English settlements without formal permission from their tribe. These incursions became extremely frequent but were conducted on a small scale; they usually involved just one or two dozen warriors, guided by a warrior chief (not a ‘sachem’, who could lead his men only when war was formally declared).

Such raids began in a very simple way: a warrior chief would send one of his messengers to all the warriors interested in joining the expedition and those who accepted would smoke some tobacco in their pipes together with the messenger who had visited them. Some time later, the warriors assembled near the house of the chief who was organizing the expedition and a ceremonial feast took place. After this, the war party started to move towards its objective with supplies including parched corn, maple-sugar, ammunitions for the muskets, black powder, materials for repairing mocassins and traditional medicines. While on the march, each war party had its own ‘pipe-bearer’ at the front (the most noted warrior who had the honour of carrying the ceremonial pipe) and the war chief at the back. A larger war party could also include a drummer and a standard-bearer who carried an eagle feather banner.

Sometimes the journey lasted for days (a native warrior from the 17th century could easily walk for 25 miles during a single day, moving much faster than any eventual white opponent) and the warriors would sleep in the forest for several nights. Songs and dances were held at nightly camps, some with religious meaning. One or more warriors transported extra ammunitions and supplies in order to provide these to their companions when needed. Attacks usually took place at the beginning or at the end of the day when the movements of the war party were more difficult to see. The attackers hid themselves in ambush positions around the enemy village/town and then attacked by surprise. Raids were mostly conducted to steal goods and supplies from an enemy, but sometimes they were organized to capture prisoners who were later employed as slaves. By the time of King Philip’s War, the practice of taking scalps from the enemy was not particularly common; it only became so some decades later when English and French colonial authorities started to pay prizes in exchange for enemy scalps.

Before the arrival of the Europeans, the native warriors of New England employed three main weapons: the bow, the stone tomahawk and the war club. The latter was a heavy and deadly weapon, made of ironwood or maple, with a large ball or knot at the end. The shaft of each war club was extremely sharp and could cause terrible wounds when used in close-combat. A war club often had a sharp-pointed horn at the shoulder, which increased its force.

With the arrival of white people, the traditional stone tomahawk was gradually replaced by a new version with a blade made of iron or steel. These new weapons were produced by colonists who sold them to the natives in great numbers. ‘Trade’ tomahawks were particularly liked by the native warriors because they were extremely resistant and easy to throw. Generally speaking, these later tomahawks were quite similar to the hatches employed by English settlers and often included a pipe bowl to symbolize their dual nature (weapon in time of war, pipe in time of peace). With the introduction of ‘trade’ tomahawks, war clubs became less popular, mostly because they were much more difficult to throw. Native bows were usually made of one piece obtained from ash/hickory/oak and arrows had triangular chert heads and were carried in quivers of cornhusk.

The arrival of white people prompted a real revolution in native warfare due to the introduction of firearms. After seeing some muskets in action, the natives soon understood their offensive potential was enormous compared to that of their bows. As a result, muskets bought from European merchants soon started to substitute bows and arrows. During the period 1640-1690, most of the native warriors of New England re-equipped themselves with muskets and deadly knives bought from European merchants and learned how to use their new firearms in a very effective way very quickly, becoming excellent marksmen (superior to most of the colonists).

The adoption of firearms also transformed the personal equipment of native warriors which started to include the following elements (mostly bought from the white colonists): one blanket, two pairs of mocassins, one multi-use tumpline, one powder horn, one bullet bag and some medicines and, as the conflict developed, and fighting became more and more intense, nothing stopped the natives from using these arms to force the ‘White man’ out of their native land.

King Philip's War 1675–76 publishes next week. Preorder your copy now!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment