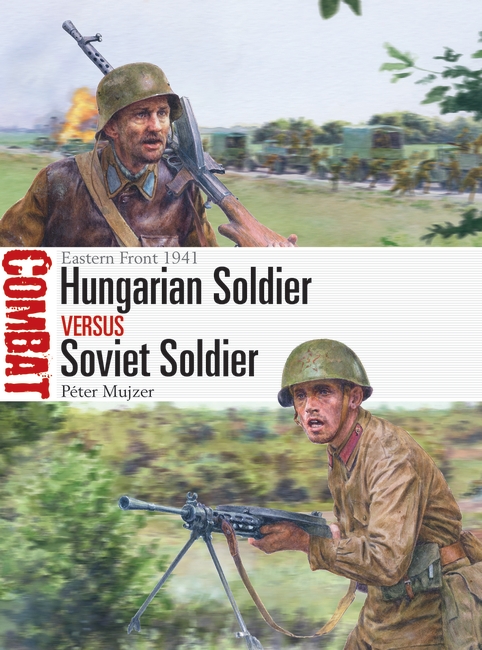

The upcoming Combat title, Hungarian Soldier vs Soviet Soldier: Eastern Front 1941 is a beautifully illustrated title that assesses the Hungarian and Soviet forces that clashed repeatedly in 1941 during the Barbarossa campaign of World War II. In today's blog post, author Péter Mujzer attempts to answer three questions that one might ask about his fantastic title.

(1) Why did you pick this subject?

The Barbarossa campaign started 80 years ago, on 22 June 1941, pitting the forces of the Soviet Union against those of the Third Reich and its allies. Hungary was among the less willing allies who participated on the side of the Germans. My specialist subject is the Hungarian armed forces during World War II, especially the so-called ‘mobile’ forces (armoured, motorized, cavalry and bicycle troops). Although Hungary and its armed forces were prepared, armed and indoctrinated to take back the territories lost after World War I, instead they found themselves on the Eastern Front amid the biggest conflict of World War II.

On the one hand, the Hungarian armed forces were not prepared to fight a war on equal terms with the Soviets, not even in the early stages of the Barbarossa campaign, due to their lack of automatic weapons, medium and heavy tanks, self-propelled artillery and combat experience. On the other hand, the personal courage, dedication of the men and junior officers, small unit cohesion and determination, and the overall military situation helped them to face and sometimes defeat a numerically superior enemy armed with sophisticated weapons.

It was fascinating to conduct deep research into the forces on the other side of the story, the Red Army. By the mid-1930s, Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky had transformed the Red Army from a basic infantry/cavalry army into a formidable mechanized/armoured fighting force, supported by airborne troops and a massive air force and tasked with carrying out so-called ‘Deep Operations’. Despite its imposing size, the Red Army was in serious disarray in June 1941. It was attempting to implement a defensive strategy with operational concepts based on the offensive deep battles and deep operations theory developed in the 1930s. In addition, it was trying to expand, reorganize and re-equip its forces. The poor performance of Soviet troops in Poland (1939) and Finland (1939–40) also hung over the Red Army. Moreover, the widespread purges of the Soviet armed forces in 1938 had effectively decapitated the officer corps.

(2) What is the special aim of the Combat series, and how is it related to this subject?

The aim of the Osprey Combat Series is to provide detailed information drawn from first-hand accounts to convey what it was like to be in combat, with the emphasis on the intensity of the front line.It is not just about the actual fighting, though, but also the two sides’ preparations for battle, their tactical doctrine and their weapons and equipment.

According to accounts from enlisted men, after basic survival, the quantity and quality of the food were the second most important issues. The looting of civilians was considered to be a serious crime in the Royal Hungarian Army, but the supply shortfall had to be addressed. Hungarian quartermasters tried to formalize their on-the-spot supply arrangements by focusing on captured and abandoned Soviet military and state-owned resources. Very soon, a kind of black market developed between the Hungarian troops and the locals, wherein people exchanged eggs, fruit and poultry for cigarettes or canned rations.

Although there was some fraternization between Hungarian soldiers and the local population, from the outset the war on the Eastern Front was conducted in a brutal way by the various participants. Some Soviet combatants involved in guerrilla operations used uniforms and equipment removed from dead Hungarian soldiers, which elicited a harsh response, both against Red Army soldiers and Soviet civilians.

(3) Who are the soldiers behind the stories?

The key figures of this study are the enlisted men, the junior officers and the battalion, brigade, and divisional commanders. Both countries fielded armies of conscripts led by professional officers and NCOs. In Hungary, the senior officers had been educated and trained before and during World War I, most of them serving on the Eastern Front. The Red Army command cadre was the product of the Russian Civil War, the purges of the late 1930s, and the Winter War against Finland.

It was also interesting to research, study and present the multi-ethnic and cultural background of the belligerent forces, especially the Red Army but, on a smaller scale, the Hungarian forces. The Soviet Union was a vast country with several minorities; the armed forces could have been a melting pot for the different ethnicities. In fact, the Red Army was dominated and led by Slavs, mostly with Russian roots; however, the average Soviet conscript could have a very different background in terms of his ethnicity, language, education, employment and place of residence. He could be an industrial worker, a peasant, a miner or a grammar-school graduate, coming from a big city or a small village. Although they were mainly Russian, Ukrainian or Belarusian, a significant proportion of the conscripts came from the Caucasian region, not even speaking or understanding the command language of Russian. Last but not least, contrary to the official atheist ideology of the USSR, a significant part of Soviet society was strongly religious, whether Christian, Muslim or Jewish. The treatment of conscripts was cruel by any standards; the physical punishment and abuse meted out was an accepted part of training in particular but also military life in general.

Hungary was predominantly an agricultural country between the world wars; the Royal Hungarian Army’s enlisted men mostly came from the countryside. They were accustomed to the hardship of heavy labour in the open air, and could handle horses and carts, which were the main method of transportation in the Royal Hungarian Army. Hungary’s skilled industrial workers were so precious that a significant proportion of them were not mobilized because their expertise was needed at home in the military industries. A significant Jewish population lived in Hungary; they were, on average, more educated, occupying middle-class positions in society. Until 1940, they were conscripted into the armed forces just like other Hungarian citizens. Due to their skills and education, they were more likely to be able to drive and to handle communication equipment and other, more complex technologies. As the war went on, however, the Hungarian government’s policies made the lives of the Hungarian Jewish population increasingly difficult. From 1940, Hungarian Jews were not allowed to serve as combat troops, and were drafted into labour companies.

Owing to the reacquisition of adjoining territories formerly parts of the Kingdom of Hungary, the country’s population changed significantly. In a population of 14.6 million people, about 81 per cent were Hungarian; the rest were German, Ruthenian (Carpathian-Ukrainian), Romanian or Yugoslavian. The male component of these parts of the Hungarian population – almost three million people – was eligible for military service. With the exception of the Germans, their incorporation into the Army generated problems. First, the language barriers were difficult to overcome. Contrary to the old Austro-Hungarian system, the Hungarian commanding officers and NCOs did not speak the languages of their men. The conscripts were forced to learn in Hungarian, but many were not willing to do so. The so-called ‘protected units’, such as the Air Force and mechanized divisions, were exempted from drafting minorities into their units. The minorities mostly served in non-combatant roles, such as supply services or labour units. However, in the hands of a dedicated commander, however, the minorities proved themselves to be as effective and loyal as the ethnic Hungarians. Moreover, the Slovakian and Ruthenian conscripts –or Hungarian comrades who spoke these languages – could use their language skills to communicate with the local population, interrogate prisoners and carry out clandestine reconnaissance patrols in Ukraine.

Preorder your copy of Hungarian Soldier vs Soviet Soldier today!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment