On the blog today, Michael Napier author of Flashpoints: Air Warfare in the Cold War takes us through what interests him in the subject.

From childhood TV images of the 1971 Indo-Pakistan War, through following the 1973 October War in the newspapers of the day and a decade later watching TV coverage of the South Atlantic War as I went through my own RAF flying training, I have always had a keen interest in those ‘little wars’ that punctuated the Cold War years. Not of course that the wars were ‘little’ ones for the participants – and it is easy to forget that those participants were real people, rather than statistics from press reports. But trying to find out about the various conflicts is difficult: of some wars there is little written, of other wars a lot – yet in all the cases the accounts are incomplete, heavily biased towards one side or the other, and often contradictory. I thought that a complete and unbiased account of these conflicts was well overdue.

As well as the major conflicts, I decided to include the Congo Crisis of the early 1960s as it gives an opportunity to study the use of air power in its purest form – without the complications of large numbers, multiple roles, and the distractions of land campaigns. On the other hand, I decided not to include the Korean War, which was the subject of my previous book, nor the Vietnam War, which lies at the opposite end of the spectrum from the Congo and would probably merit one or two volumes of its own. The result is what I hope are comprehensive accounts of the Suez Crisis of 1956, the Congo Crisis of 1960–64, the Indo-Pakistan Wars of 1965 and 1971, the Arab-Israeli Wars of 1967 and 1973, the South Atlantic War of 1982 and the Iran–Iraq War of 1980–88.

My interest is at the operational level, rather than a strategic overview, although for each conflict I have included an ‘executive summary’ of the strategic context. I think that it is important to record the human element of aerial warfare – after all, aircrew are real human beings rather than faceless numbers – so I have included as many names as I can and have recorded the activities of specific units, too. To the flier, a squadron or wing is as much a family as their own blood, and the exploits and sacrifices of each unit deserve to be documented. I have also included some contemporary first-hand accounts to give a flavour of what it was like to be there and to fly in combat.

Another fascinating aspect of the conflicts is the plethora of ‘unusual’ aircraft types that were involved, including the Westland Wyvern, the Saab J-29, the Folland Gnat, and the HAL Marut. Of course, there were also the major types that also equipped the front-line air forces of NATO and the Warsaw Pact, such as the F-86 Sabre, the MiG-19, the F-4 Phantom, the MiG-21 – and the ubiquitous Mirage, which participated in five of the eight conflicts described.

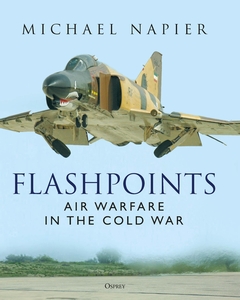

F-86 Sabres of the Imperial Iranian Air Force at Kamina, 1963

(Gilbert Casselsjo/Swedish Air Force Museum)

Each of the conflicts is fascinating in its own right, so this book is full of interest to the historian and the enthusiast alike. In addition, it serves as a good starting point for a deeper study of any of the conflicts. I have also drawn the lessons of air power from each chapter and identified where those lessons were learnt – or not – in subsequent campaigns.

I was delighted to persuade Israeli Mirage pilot Itamar Neuner to write a foreword to the book. Apart from being a distinguished and successful veteran of the ’67 and ’73 wars, Itamar is an accomplished writer, and his words also serve to bring home the reality of warfare: ‘wars mean family and close friends lost, injuries that remain for life, husbands and wives becoming widowers or widows, children becoming orphans after having lost their parents in battle. In time, you may forget the bombs exploding, the mayhem, ruins and destruction, but the family and friends you lose, those memories will stay with you for the rest of your life.’ His eloquence is prescient in the light of the current hostilities in Ukraine and we can only agree with his sentiment that ‘maybe, just maybe, major outbreaks of war will become an element of the past, never to occur again.’

I hope that by reading about and learning from past conflicts, people will learn enough to ensure that Itamar’s hopes for a future free of warfare will be realised.

Flashpoints is availabe in hardback and digital formats on our website

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment