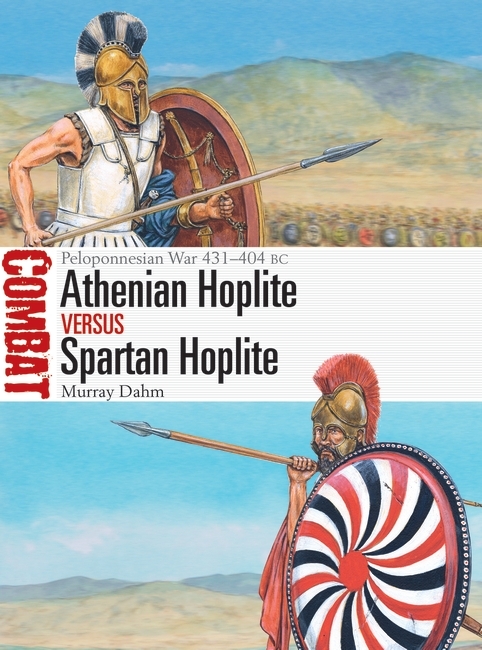

On the blog today, author Murray Dahm shares some of the interesting facts he uncovered while researching his upcoming title, Athenian Hoplite vs Spartan Hoplite.

The Peloponnesian War, fought between Athens, Sparta and their respective allies during 431-404 BC, continues to be a fascinating and rewarding conflict for the military historian. Researching this conflict for Athenian Hoplite vs Spartan Hoplite, I found so many tidbits of information and insights into ancient warfare which I had not noticed before, and so many avenues of for research that it was a struggle to fit them all in. (In fact, we couldn’t, and I have a long list of topics to explore which have arisen from researching this Combat title.) It never fails to surprise me that studying ancient conflicts (in this case one fought 2,450 years ago) you can find new things to consider time and time again. Every re-reading of the sources uncovers some new topic of study. Often, each and every one of these topics is an intriguing wormhole of their own. I thought I would touch on a few of these here to whet your appetite for Athenian Hoplite vs Spartan Hoplite.

The strength of the Athenian lochos.

We know that the Athenian army was commanded by strategoi (generals, sing. strategos); ten were elected every year. Below that, an expedition of Athenian hoplites would be selected (usually by age groups – Athenians were eligible to be called up as hoplites from the age of 18 to 60 – 42 years of service). Athenian armies were divided into tribal taxeis – there were ten tribes (or phylai) at Athens, so each army would have ten taxesis. These could be of different strengths – we have expeditions of 1,000 hoplites, 2,000 all the way to 7,000, and in each one there would be ten tribal divisions. Each taxis would be commanded by a taxiarch. Below the taxis was a certain number of lochoi (sing. lochos) (and each commanded by a lochagos); we do not know how many there were nor do we know how many men were in each one. There are different arguments for their strength. For the Spartans, however, we have very precise details – ironically from Athenian authors (who don’t provide such detail for their own armies!). The (Athenian) historians Thucydides and Xenophon provide us with very precise breakdowns of the Spartan army – commanded by the king or the polemarch, they had five lochoi (the same term as in Athenian armies but a larger division of men). Below that were pentekostyes (it may have meant ‘fiftieth’), and each lochos had four pentekostyes. Each pentekostyes had four enomotiai (sing. enomotia). With an enomotia strength of 32 men, each pentekostyes had 128 men, and so each lochos had 512. These divisions (based on Thucydides account of the battle of Mantinea in 418 BC) allow for a very precise breakdown of Spartan manpower (something we cannot do for the corresponding Athenian armies). There are some complications – Xenophon uses the term morae (sing. mora) later in the war so there seems to have been a change at Sparta, perhaps brought on by the losses the Spartans suffered at Sphacteria in 425 BC. And in this Xenophon and Thucydides do not entirely agree (although it is possible to reconcile their accounts).

Socrates

Another surprising thing about the Peloponnesian War is that we find the most remarkable detail about an individual hoplite, the Athenian philosopher Socrates. In ancient wars we are used to getting details of commanders; it was their conduct that was recorded in ancient historical and biographical accounts. In the Peloponnesian War, however, every Athenian was expected to serve in the armed forces and the philosopher Socrates did his civic duty better than most. We know he was relatively poor but served as a hoplite. What is more, we know that he served in three campaigns during the war (Potidaea in 432/431 BC, Delium in 424, and Amphipolis in 422). Because Socrates was so important to philosophy, its patron saint, we have an abundance of sources for his life and philosophy from Plato and Xenophon and a multitude of other sources outside of traditional historical accounts. Many have a military context, and these combine to make Socrates the Greek hoplite about whom we know the most detail. Socrates never held a position of command and he is absent from the historical records of the battles he was involved in, but we can use the additional detail we have to reconstruct the most remarkable military biography of the most famous Greek philosopher, courageous in battle and admired by his colleagues on campaign.

Battles you should know better

There are battles in the Peloponnesian War which are well known (Pylos and Sphacteria, the Sicilian Expedition) but there are others which should be better known; two of those I got to explore (along with Sphacteria) – the battles of Amphipolis and Mantinea. And study of them rewards the researcher again and again. There are others too. The battle of Olpae (a small town in Acarnania), fought in 426 BC, showed the Athenian general Demosthenes (who would win on Sphacteria later die in Sicily) at the height of his powers. Demosthenes had suffered a setback earlier that year and so refused to return to Athens where he was sure he would be prosecuted (one of the great weaknesses of the Athenian system – they punished their best generals for failures, many of which were beyond the individual commander’s control). Demosthenes took a force of 200 Messenians and 1,000 Acarnanians (along with only 60 Athenian archers) and defeated a far superior force of 3,000 Spartans and their allies. Demosthenes did this by stationing a force of 400 hoplites and lightly armed troops in a ravine behind where the Spartans would attack him. At the right moment, this force emerged and attacked the rear of the Spartans, killing both commanders. The remainder of the Spartan force saw the Spartans themselves defeated and they fled. This battle deserves to be better known – the perfect use of an ambush, the cutting down of the Spartans (and their leadership) which caused the remainder of their allies to flee, and a defeat of a numerically superior foe (the Spartans outnumbered Demosthenes’ forces by more than 2:1). There were lessons to be learned from this battle which would not be put into proper effect until the following century.

Amphipolis is a remarkable battle, fought far away from the cities of Sparta and Athens but between Spartan and Athenian forces. We see in this battle the use by the Spartan commander, Brasidas, of a force of only 150 selected hoplites ordered to charge a much larger force – probably one of 600 Athenians. Brasidas’ charge was unexpected but caused havoc – he lost only seven men (including his own life) but inflicted more than 600 on the Athenians. Mantinea too deserves to be better known – it is from this battle we get all the detail of Spartan divisions as well as the idea that Greek armies shuffled to the right as they advanced, as each man sought the protection of his neighbour’s shield on his exposed right side. This is likely to have been a factor in many battles but it is explicitly mentioned in accounts of Mantinea.

Elites

The battles of the Peloponnesian War also reveal the use of several elite forces – not only the 150 of Brasidas but also the more famous hippeis bodyguard of the Spartan kings, who fought at Mantinea. There are many others in evidence; men especially selected for a particular mission or to fight in the front ranks. We have the Boeotian ‘charioteers and footmen’ who formed the front rank at the battle of Delium in 424 BC (another battle which deserves to be better known), and 1,000 picked Argives at Mantinea. We also have a perplexing case of a unit of 300 Athenian hoplites who may have been a longstanding elite (stretching back to the battle of Plataea in 479 BC). Other cities had elite units too.

There is a seemingly endless amount of information and insight to be found in accounts of the battles of the Peloponnesian War. Almost every battle and factor involved contains a historical conundrum or discrepancy between sources. Some of these can be worked out, others provide yet more fuel to further thought and analysis, but all are fascinating and worth exploring again and again.

Athenian Hoplite vs Spartan Hoplite publishes 21 January. Preorder your copy now!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment